Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1516 CE) was an Italian Renaissance artist best known for his innovative use of colour, interest in light, and emphasis on brushwork. Today, Giovanni is recognised as the most innovative and influential of the Bellini family of painters and his works range from portraits to altarpieces. Masterpieces include the superbly detailed and naturalistic Ecstasy of Saint Francis painting and his hyper-realistic Portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan. Bellini's work was hugely influential on his Venetian contemporaries, and this continued through the work of his pupils, amongst whom was Titian (c. 1487-1576 CE).

The Bellini Family

Giovanni Bellini was born c. 1430 CE, the son of the well-known Venetian artist Jacopo Bellini (c. 1400 - c. 1470 CE). Giovanni's elder brother was Gentile Bellini (c. 1429-1507 CE), who also became a celebrated artist. Gentile Bellini was highly successful as a court artist for Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1452-1493 CE) and Sultan Mehmed II, ruler of the Ottoman Empire (r. 1444-46 & 1451-81 CE). Gentile also worked on several commissions for the Doges of Venice, but despite these illustrious clients, it was Giovanni's contribution to western art that would be more esteemed by the critics of subsequent generations.

The Bellini family of artists worked closely together in the same workshop in Venice. The two brothers are known to have collaborated on some of their father's works, for example, on the Descent of Jesus into Limbo altarpiece panel, now in the Museo Civico of Padua. Giovanni even finished off his brother Gentile's painting Saint Mark Preaching at Alexandria, now in Milan's Pinacoteca di Brera. Indeed, accurately attributing certain works to Giovanni is problematic because of the large number of assistants working in the Bellini family workshop and the artist's varying style over the years. Finally, another family artistic connection was Giovanni's brother-in-law, Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506 CE), who had married his sister Nicolosia and who was famous for his innovative use of perspective in paintings and frescoes.

Early Works

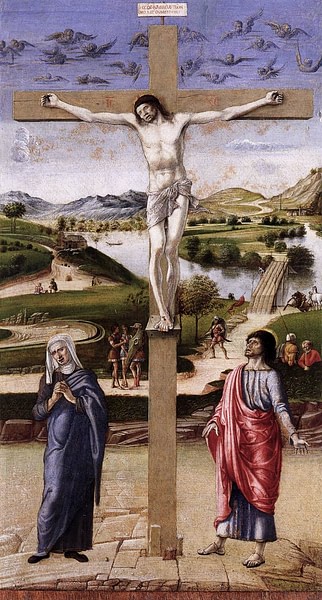

Although he used some of his father's ideas from sketchbooks, Giovanni's style would eventually depart dramatically from that of his father which, in the few surviving works, is rather austere in comparison. Like other Renaissance artists, Bellini was very interested in giving his paintings a sense of depth and perspective. This can be seen in such works as the Crucifixion of the mid-1450s CE and the c. 1465 CE tempera on wood piece The Agony in the Garden (National Gallery, London). In the former painting, Bellini seems to have been far more concerned with depicting a realistic panoramic background than the principal figures in the foreground. There is real depth as a snaking and seemingly interminable roadway eventually fades away into the distant hills. Another remarkable feature is the vaguely defined swirl of cherubims above the Cross. The tonal colouring and elongated figures are typical of Bellini's early work and remind of his father's style. Another example of the artist's use of sombre colouring for scenes of grief early in his career is his Dead Christ Supported by the Madonna and Saint John, painted in the mid-1460s CE and now in Milan's Pinacoteca di Brera.

Into Colour

Mid-career, Giovanni seems to have switched his focus to the colore technique (aka colorito), that is using the juxtaposition of contrasting colours to define a composition. This may reflect the influence of the celebrated oil painter Antonello da Mesina (c. 1430-1479 CE) following his stay in Venice between 1475 and 1476 CE. Messina had himself been in contact with the methods of Flemish oil painters who were pioneering in their realism in art. The Doge Leonardo Loredan portrait (National Gallery, London), painted c. 1500 CE, is a good example of Bellini using this technique in action. The portrait is so hyper-realistic, it looks curiously like a coloured two-dimensional version of a sculpture bust. The fine details in the painting may reflect the influence of the German painter Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528 CE), who was much admired by Bellini for the precision of his brushwork. Another development in Bellini's work was to use the much more versatile medium of oil painting instead of tempera which he had almost exclusively used in the earlier part of his career. Oil paints allowed for brighter, richer colours, greater layering, and faster work.

A painting where the light source is being used to add colour to the scene and to pick out background elements in great detail is the Ecstasy of Saint Francis (aka St. Francis in the Desert), completed by 1480 CE and now in the Frick Collection, New York. The light seems to be positively bathing the saint and the desk behind him. Another interesting feature is the number of objects and animals painted by Bellini to symbolise episodes from Francis' life or to indicate poverty and humility, the main principles by which members of the Franciscan order lived. To modern eyes, the figure of Saint Francis seems incidental to the landscape background with its looming grey cliffs and distant fortified town. As the art historian and former director of London's National Gallery Philip Hendy notes, Bellini "became one of the greatest of landscape painters. His study of outdoor light was such that one can deduce not only the season depicted but almost the hour of the day". It is rather curious that a painter living in water-soaked Venice should develop such a passion for landscapes.

As Bellini's style changed so, too, did the focus of his subject matter: from religious devotional scenes to many more naturalistic mythologies in the latter part of his career. See, for example, his bright and playful Feast of the Gods painting now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Another late development in Bellini's work was the adoption of a more erotic approach to female figures, in keeping with the general trend in Renaissance art of the early 16th century CE. Throughout his career, Bellini was commissioned by figures of wealth and importance, but they were not quite the high and mighty patrons of other Renaissance artists such as the Pope for Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) and Cosimo I de' Medici, Duke of Florence (r. 1537-1569 CE) for Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571 CE). It was not easy to persuade such strong-minded figures to accept innovations and so here perhaps Bellini had the advantage of some other great artists.

Altarpieces

Bellini produced five major altarpieces for churches from the 1470s CE to 1513 CE. These were for the Pesaro, Frari, San Giobbe, San Zaccaria and the San Giovanni Crisostomo in Venice. The central panels of these altars are in the sacra conversazione theme, that is the Virgin and Child surrounded by saints and well-wishers. Monumental pieces several metres high, the altar panels are elaborately framed to mimic contemporary developments in architecture and are much larger and more eye-catching than altarpieces then being produced elsewhere, such as in the Netherlands. In a nod to Venice's Byzantine history, some of these altarpieces include gold mosaic effects in the domed interiors of the background architecture.

The San Zaccaria piece is often considered the finest of the lot and, completed c. 1505 CE, it is curiously pious and tranquil. This mood, best seen in the 5 metres (16 ft 4 in) high central panel, is achieved by the symmetrical architectural background, which is curiously open at the sides to a landscape of trees and so not meant to merely extend the walls of the church. A more explicit calming effect comes from the reduced number of figures than was traditional in such scenes and the arrangement and attitude of those figures, all of whom are gazing downwards. There are, too, little tricks of perspective which seem to give the figures more space to exist in. These techniques include the columns behind columns, the checkerboard flooring, and the domed ceiling. Despite the tranquillity of the scene, Bellini has not neglected his love of colour, as seen in the vibrant robes of blue, red, yellow, and green.

The Great Council of Venice

Despite his successes, Giovanni was still somewhat overshadowed by his brother Gentile in his own lifetime, largely because of his seniority in age. An example of this is the commission for Gentile to complete a large cycle of historical paintings for the Great Council of Venice. However, in 1479 CE Gentile was dispatched to Constantinople on a diplomatic mission and Giovanni was the natural choice to continue the work. This he did, adding perhaps seven entirely new paintings to the collection. Critics regarded these new canvases as amongst the artist's best ever, but unfortunately for posterity, a fire ravaged the building a century later in 1577 CE and destroyed all of the artwork.

Legacy

Always a prolific painter, Bellini kept on working into his eighties. Later masterpieces include The Drunkenness of Noah (1514 CE) and the Lady at her Toilet (1515 CE). As the famed German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer stated in 1506 CE, Bellini "was very old, but still the best in painting" (Hale, 47). Bellini died in Venice in 1516 CE and was buried alongside his brother in the city's Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Giovanni Bellini influenced Renaissance art not only through his own work's effects on his contemporaries but also via three of his most famous apprentices: Palma Vecchio (c. 1480-1528 CE), Giorgione (c. 1478-1510 CE), and Titian. In short, Bellini's works, workshop, and pupils together ensured that instead of the previous dominance of line and form, now colour and brushstrokes took precedence in Renaissance art. As the Thames & Hudson Dictionary of the Italian Renaissance boldly states, "Bellini changed the course of Venetian painting and laid the foundations for a revolution in the history of European art." (46).