The Ghent Altarpiece, otherwise known as The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, is a painted panel altarpiece created in 1432 for the Vijd Chapel in the church of St. John the Baptist, now St. Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium. The work is credited to Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441) or Hubert van Eyck or both artists.

Widely considered one of the masterpieces of Renaissance art, the altarpiece panels show scenes rendered in vibrant oil paints which have a collective theme: the redemption of humanity. Saved from destruction at the hands of Reformists, looted by the armies of France once and then Germany twice, it is today back in the church for which it was commissioned.

Authorship

Exactly who created the Ghent Altarpiece is still being debated by scholars. The artist most frequently associated with it is the Belgian master Jan van Eyck who was famous in his own lifetime for his great skill using oil paints. Even before the Ghent commission, he had already established himself as a renowned artist, working for the likes of John III, Duke of Bavaria and Count of Holland (l. 1374-1425), Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (r. 1419-1467), and John I of Portugal (r. 1385-1433). Van Eyck had a particular mastery of colouring and producing naturalistic scenes. Another notable trait was his eye for minute detail and use of the finest of brushes to achieve it. All of these characteristics can be seen in the Ghent Altarpiece.

A second artist connected to the work is Hubert van Eyck (d. 1426), possibly the elder brother of Jan, but certainty is lacking as he remains a mysterious figure. There is an inscription in Latin on the altarpiece itself which, translated, states:

The painter Hubert van Eyck, a greater than whom cannot be found, began this work; Jan, his brother, second in art completed the heavy task at the request of Joos Vijd. On the sixth of May he invites you to look at what has been done.

(Nash, 12)

The authenticity of this inscription, which is actually a 16th-century transcription of the (possible) original, has been questioned by some art historians and linguists. Other historians have accepted the inscription and so tried to identify which panels were painted by which brother, although no consensus has been achieved there either. The major problem is that there are no other references anywhere else to Hubert's involvement in the piece, and comments on it by such figures as Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), who saw the altarpiece in person in 1521, make no mention of anyone except Jan van Eyck. Neither does the historian Marcus van Vaernewyck when he referred to the altar in 1562. There was really, it seems, a Hubert van Eyck as he appears three times in the municipal archives of Ghent. However, dating of the wood in the side panels using dendrochronology tests show that the trees were felled around 1421. Since the wood then had to be seasoned for at least a decade, these panels, at least, cannot have been painted by Hubert who died in 1426. As the art historian H. L. Kessler summarises, "whether this Hubert van Eyck was related to Jan and why in the 16th century he was credited with the major share of the Ghent Altarpiece are questions that remain unanswered."

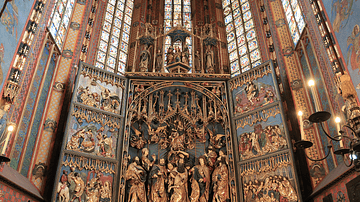

Panel Altarpieces

Altarpieces had become a standard feature of churches since the 13th century. They are designed to stand either on or just behind the main consecrated altar or subsidiary altars within the church. These artworks thus became the focus of the congregation's attention during a service, and they showed scenes from the Bible relevant to that particular church, its benefactors, and even the particular service being performed. The Ghent Altarpiece is an example of the polyptych type which has multiple panels designed to be closed by folding the hinged side panels. This design was particularly popular in northern Europe, and it allowed the main central images to be better protected when not in use and to create a sense of revelation when the altarpiece was fully opened on special occasions.

The Ghent Altarpiece is composed of 12 framed panels of Baltic oak which have been painted on both sides using oil paints. First, a preparatory layer of ground chalk and animal glue was applied to the wood, then a line drawing was made to guide the painter, then a lightly tinted but still transparent priming layer of oil was added which kept the line drawing visible. Finally, oils paints were used and scenes were rendered with a three-dimensional appearance using effects of colouring and shading. The figures in the scenes are given hyperrealistic details which are only fully appreciated by viewing the work at close quarters. Seen by the congregation from afar, the viewer would have been most struck by the vibrant, jewel-like colouring and the simulated gold leaf that, combined, would have made the scenes shine out from the dim recess in which the altar was placed.

The altarpiece carries a date: 6 May 1432. When fully opened, the altarpiece measures 5.2 x 3.75 metres (17 ft x 12 ft 4 in). It was originally meant to stand in what was then the Vijd Chapel of the church of St. John the Baptist, which has since become St. Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium.

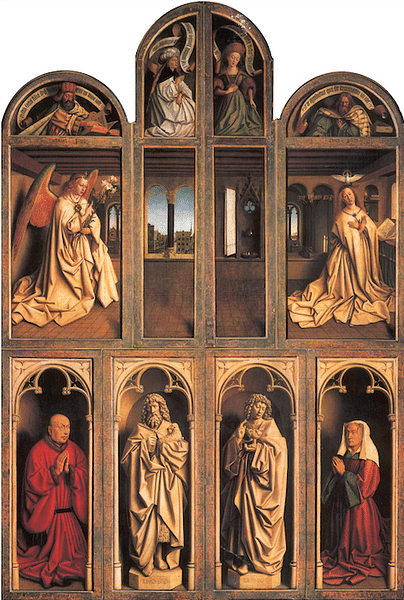

The Outer Panels

The altarpiece was commissioned by Jodocus (aka Joos) Vijd, and he appears in the bottom left outer panel; his wife, Elizabeth Borluut, appears in the lower right panel. The other panels on the exterior side show an Annunciation scene. In the centre, there is an interior of a room looking out onto a town landscape. At the top of the piece, there are (left to right) representations of the prophet Zechariah, the Erythrean Sibyl, the Cumaean Sibyl, and the prophet Micah. Either side of the architectural scene is the Archangel Gabriel (left) and the Virgin Mary (right). The two lower central panels show Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Apostle/Evangelist, both masterfully painted to appear as sculptures.

The Inner Panels

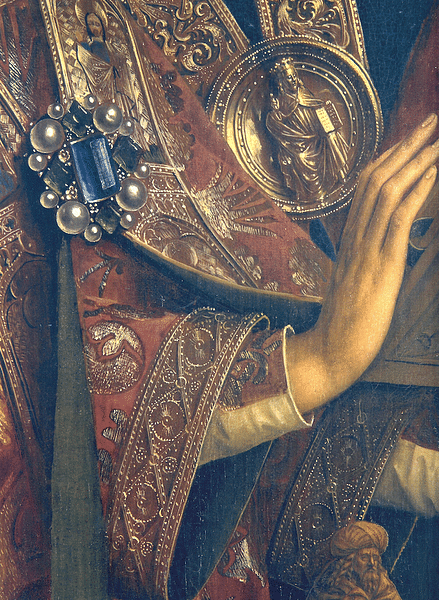

The interior side, and particularly the central part of altarpieces were typically reserved for the best artwork since these were not only the largest and most visible but could be protected by folding the wings closed. Consequently, the artist is more ambitious here and uses more expensive colour pigments such as blue, red, and greens.

The upper central panels of the interior show God enthroned, while on the left is the Virgin Mary and on the right is Saint John the Baptist. The panels on either side of this central trio show various angels singing and playing the organ. The panel on the extreme left shows a naked Adam with a tangible expression of anxiety and minute details shown such as veins and hairs. The figure appears to be moving towards the viewer due to the use of shadows behind him and the raised toes of Adam's right foot as if he is taking a step forward.

Adam also reminds of the Renaissance interest in classical art as he is depicted in the pose of the Venus Pudica ('Modest Venus'). The far-right panel shows Eve. Above both Adam and Eve is a small curved panel showing fictional sculpture. Over Adam is a relief scene showing the Sacrifice of Cain and Abel, above Eve is a similar work depicting the Murder of Abel.

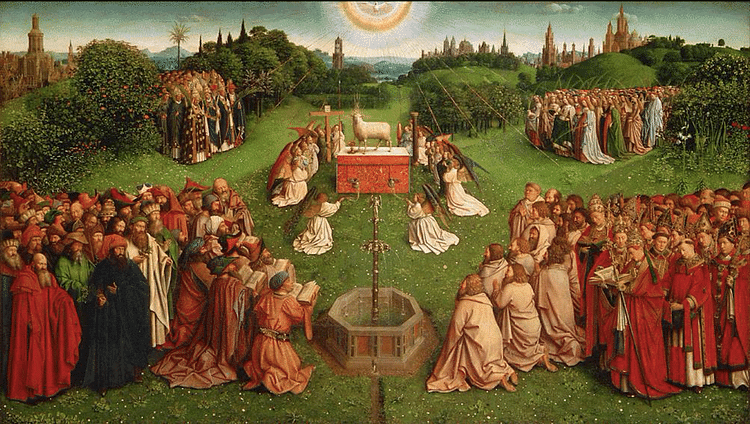

The lower central panel, the largest by far of all the panels, gives the altarpiece its name – The Adoration of the Lamb of God by the Elect or Adoration of the Mystic Lamb – and shows a crowd worshipping a lamb, symbol of Jesus Christ and his sacrifice at the crucifixion. Above the lamb is the dove of the Holy Spirit. The illustrious crowd on either side of the lamb consists of saints, apostles, martyrs, and confessors. The panels on either side show approaching judges and knights on the left and hermit and pilgrim saints on the right. The overarching theme of all the panels on both sides seems to be the redemption of humanity.

Later History & Recovery

The Ghent Altarpiece was immediately recognised as a masterpiece, so much so, it soon came to be seen as one of the defining works which marked the beginning of Renaissance art. Noted 16th-century art historians like Ludovico Guicciardini (1521-89) and Karel van Mander (1548-1606) began their overviews of the period with the Ghent Altarpiece. The work was admired by all types, from the master Albrecht Dürer to Antonio de Beatis (secretary to the Cardinal of Aragon). Dürer noted the altarpiece was "a most precious painting, full of thought" (Nash, 36) while de Beatis went further, describing it in 1517 as "the finest painting in Christendom" (Nash, 11).

The altarpiece, precisely because of its quality and fame, has been obliged to endure a remarkably troubled history. It was first threatened with destruction during the 16th-century Reformation when any ornate visual art in churches was regarded as superfluous. In 1566, when iconoclastic rioters roamed Ghent destroying religious art, the work was dismantled into its component panels and stored in the church's tower. Brought back down, it was again hidden when a second wave of icon-smashers came along a decade later.

French soldiers stole four of the panels for Napoleon's new museum in Paris in the 18th century. Put on show in the Louvre, the panels were not returned to Ghent until 1815. The next hiccup was the decision by a canon to sell some of the wing panels to a local art dealer; they were eventually returned following public outrage at the act.

The altarpiece was stolen by German troops in the First World War (1914-1918) but so concerned were the victors to have it back again that the altarpiece was specifically mentioned in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The treaty contained a clause that Germany had to return the altarpiece to the people of Belgium. It was returned, but the rising prices of art tempted thieves to take two panels in 1934. One of these panels was recovered, but the other has never been found. The missing panel showed the Just Judges (lower left interior panel) and has been replaced by a copy.

The entire altarpiece was stolen again by the German occupiers of Belgium during the Second World War (1939-1945). Fortunately, the altarpiece was recovered from its hiding place in an Austrian salt mine by U.S. troops in 1945. Later in the 1940s, it was the first work of Renaissance art to undergo detailed scientific analysis. Today, the altarpiece is back where it belongs in the Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, although it is not in its original position. Restoration work was carried out on the altarpiece between 2012 and 2020. The Ghent Altarpiece continues to inspire and fascinate, its dramatic recovery after WWII being featured in the 2014 film The Monuments Men.