Paolo Uccello (1397-1475 CE), real name Paolo di Dono, was an Italian painter who is considered one of the founding fathers of Florentine Renaissance art. Uccello was one of the earliest artists to attempt certain tricks of perspective in his paintings. His most famous works include the paintings Saint George and the Dragon and The Hunt, as well as various frescoes such as the Deluge in Florence's Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. The artist's final commission, the series of panels known as the Miracle of the Desecrated Host, contains more fine examples of his work using perspective.

Early Life & Style

Paolo di Dono was born in Florence in 1397 CE. He first trained as a goldsmith and then joined the workshop of the famed metalsmith and sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE). Ghiberti was busy on his first set of bronze doors for Florence's Baptistery, and Uccello studied as the sculptor's apprentice from 1407 to 1412 CE. Uccello must have switched media at some point because in 1415 CE he joined Florence's Physicians' Guild as a painter. Clearly versatile, one of Uccello's first public projects was in 1425 CE to create a mosaic for the facade of Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice. The artist spent around five years in that city before returning to Florence.

Uccello's art is characterised by a love of detail, vibrant colouring, graceful lines, and experimentations with perspective. Uccello's search for realistic perspective in his paintings was amongst the earliest in Renaissance art, although he did not always attempt the more precise and mathematical perspective of those artists who followed. Uccello seems to have been more interested in using perspective for whimsical effect rather than to capture reality per se, and his sometimes lack of success in accurately recreating scenes with a true perspective was a source of criticism from such early and influential art historians as Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574 CE), who wrote The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors (1550 CE, revised 1568 CE). Vasari explains why Paolo di Dono got his lasting nickname 'Uccello' because he was always drawing wildlife, especially birds, which in Italian is uccelli in the plural and uccello in the singular. Vasari also expressed the opinion that Uccello, although he had the potential to equal the very finest of artists, sometimes concentrated so much on perspective that he forgot to render his figures properly, a fault he thought only got worse as the artist got older. This was an opinion shared by his friend and fellow Florentine artist Donatello (c. 1386-1466 CE), at least according to Vasari.

Despite the criticism, Uccello was recognised as an innovator, and it is significant that he appears in a late 15th-century CE tempera panel, now in the Louvre in Paris, titled the ''The Founders of Florentine Art'. Credited to Masaccio, the work shows five portraits: Giotto (b. 1267 or 1277 - d. 1337 CE), Uccello, Donatello, Manetti (1423-1497 CE), and Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446 CE).

Major Works

Uccello was commissioned by the Signoria of Florence to produce a fresco for Florence's cathedral and the result was an equestrian portrait of the mercenary commander (condottiere) Sir John Hawkwood (c. 1320-94 CE) who had led the city's forces against those of Luca in a four-year war from 1429-33 CE. Completed in 1436 CE, the work was an imitation of an existing sculpture of Hawkwood. The preparatory drawing for this fresco survives and shows that Uccello worked on a precise grid plan. This is the earliest surviving example of such a drawing although other artists are known to have used the grid technique, notably the famed artist and architect of Florence's cathedral dome, Filippo Brunelleschi (who likely taught Uccello the technique). The finished fresco measures an impressive 7.32 x 4.04 metres (24 ft. x 13 ft. 3 in.) and, using trompe l'oeil, captures the statue as if it is three dimensional. The frame it is set in today was added in the 16th century CE when the fresco was transferred onto canvas. Today the work hangs on the north wall of the cathedral's nave.

Now established as a successful artist, Uccello bought a house in Florence in 1442 CE. Around 1445 CE, Uccello finished his fresco the Deluge in the Chiostro Verde (Green Cloister) of the Santa Maria Novella Basilica in Florence. The work has deteriorated badly over the centuries but it remains a striking example of Uccello's skills at achieving a sense of depth in his scenes.

Around 1455 CE, he completed his Battle of San Romano paintings, a series of three panels which commemorated the battle between Florence and Siena in 1432 CE. Commissioned by the powerful Medici family to decorate their palace interior, the panels now find themselves, unfortunately, in three separate locations: the Uffizi Gallery of Florence, the Louvre, and the National Gallery in London. The colourful panels, which measure some 1.8 x 3.2 metres (6 x 10.5 ft.), almost have the appearance of a tapestry and are a good example of how late medieval art was developing into what would eventually become High Renaissance art with its greater emphasis on classical motifs, dynamic poses, and effects of perspective. For the latter technique, see, for example, panel two and the foreshortened dead horses in the foreground. The rear-kicking horse is perhaps a less successful attempt at perspective but illustrates Uccello's willingness to experiment and capture unusual postures in his figures, human or otherwise. Another rewarding examination is to see how carefully Uccello has arranged the lances throughout the three scenes to create precise angles in what should really be a subject characterised by the chaos of battle.

The Hunt was painted around 1460 CE, although it may date to the next decade. It is now on display in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England. A large painting, well over one and a half metres wide but only 65 cm (25 inches) high, it has the effect of a panoramic view of a hunting party. It is a triumph of perspective with the symmetrically placed trees placed in lines which disappear into the background. The human and animal figures are so arranged as to almost act like the paving stones of many other Renaissance paintings which lead the viewer's eye into the very centre of the picture. The hunters, beaters, and hounds converge from either side of the painting along diagonal lines and diminish in size as they head to the dark interior of the forest, a technique which gives the scene a palpable sense of the chase as they pursue their quarry.

St. George and the Dragon was completed c. 1470 CE. The painting has the usual figure of a mounted Saint George spearing a dragon while a damsel looks on from the side. Uccello adds his own take on the scene by foreshortening the dragon's neck to give an effect of depth and adding the dripping blood from its mouth in an unusually graphic touch. Further, this is another piece that shows Uccello's love of perspective, although the square pieces of grass across the scene's paved flooring seem somewhat unnatural and superfluous to a mythological subject, and one made on such a small scale. The panel, which measures 74 x 54 cm (29 x 21 inches), now resides in the National Gallery, London.

A Study in Perspective

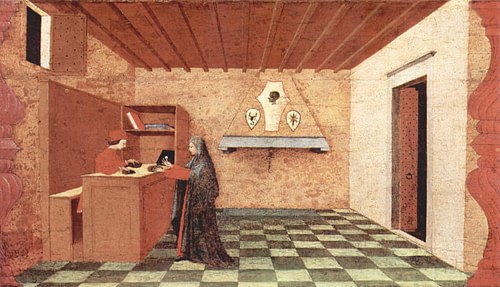

An unusual work was produced from c. 1468 CE, the Profanation of the Host (aka Miracle of the Desecrated Host). Composed of six panels, now in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, the work was meant for the altarpiece of the church of Corpus Domini in Urbino. The panels tell the story of a woman who steals a consecrated host in order to repay a loan to a Jewish moneylender. The authorities find out about this sacrilegious act and apprehend both of them. The woman is hanged while the moneylender is burnt at the stake. Each panel measures 58 x 43 cm (23 x 17 inches).

The first two panels are particularly noteworthy for their perspective, seen in the angles of the room and the representation of the black and white checkerboard flooring which creates lines leading to a single centric or vanishing point. The first panel in this group was used as an example by Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472 CE) in his discussion on perspective in his influential treatise On Painting (1435 CE). Rather than being a technique to create abstract space, though, this approach was pursued to ensure that objects within a given space had the correct proportions to each other. However, it is true that Uccello's vanishing point is carefully chosen: the exact centre of the picture, which is also where the chimney hood begins and it is the level of the woman's eyes. The Profanation of the Host was Uccello's last documented commission.

Uccello died in 1475 CE, apparently in a state of loneliness and poverty after his work was no longer admired as it once had been. Fortunately, posterity has been kinder to Uccello than critics like Vasari and Donatello, and he is now esteemed as one of the early champions of perspective and so a source of inspiration to later Renaissance artists like Leonard da Vinci (1452-1519 CE) and Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE).