Giotto di Bondone (b. 1267 or 1277 - d. 1337 CE), usually referred to as simply Giotto, was an Italian painter and architect whose work was hugely influential in the history of Western art. Giotto is most famous today for the cycle of frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel of Padua where his love of drama is most effective in such scenes as Judas' betrayal of Jesus Christ. An innovative painter who searched for far greater realism and human emotion in art than had been seen previously, he was an artist with a particular skill at constructing single dynamic scenes from familiar religious themes. Often referred to as the 'first Renaissance painter' even if he lived before the Renaissance proper had got underway, Giotto was certainly a bridge between the sometimes flat, characterless religious art of the middle to late medieval period and the lively innovative drama seen in the masterpieces of the High Renaissance.

Early Life

Giotto di Bondone was born in either 1267 CE or 1277 CE; the dates, like the exact place of his birth, are disputed amongst historians. His family was a humble one according to an anecdote told by the art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574 CE). Vasari informs us that the famed artist Cimabue was one day travelling from Florence to Vespignano in Tuscany when he came across a boy looking after a herd of sheep. The boy seemed about ten years old and was busy scratching a picture of a sheep on a stone slab using the sharp point of another stone. Impressed with the picture, Cimabue asked the boy's name and he replied, "I am called by the name Giotto" (Woods, 25). Cimabue promptly invited the youngster to train with him in his workshop in Florence and by his teenage years, Giotto was already an accomplished artist and creating painted panels for churches. By his early twenties, he had moved up to frescoes and was the complete article, a member of Florence's guild of painters. Modest, stocky, and far from being handsome, Giotto was hardly the archetypal artist but his works would speak for themselves.

The former apprentice was by now even outdoing his old master. Giotto was faced with an endlessly repetitive cast of biblical figures who had up to then appeared in paintings, murals, and icons as no more than conventional representations one was supposed to pray to rather than admire. Like Cimabue but going much further, Giotto was interested in presenting these all-too-familiar figures as looking like real people and expressing real emotions. An excellent example of this new approach can be seen in Giotto's Madonna, a tempera on wood panel now in the Borgo San Lorenzo of Florence. Another Madonna, the altar panel known as the Ognissanti Madonna (of All Saints), is similarly painted and suggests, too, that Giotto is using live models to aid him in his search for real facial expressions. The latter work is now in the Uffizi Gallery of Florence.

The Revolutionary Artist

Giotto moved away from the conventions of medieval art in several important ways, just as near-contemporary sculptors like the Pisano brothers had been doing in marble. The artist skilfully used highlights and shadows to create the illusion of depth in his scenes and roundness in his human figures which are given realistic expressions. He also painted elements of architecture in detail and in three dimensions. Finally, the light source within the scene in question is often clearly indicated. Combining these skills with a masterly appreciation of how to best represent famous biblical episodes in a single, emotionally-charged scene captured at a dynamic moment in time, Giotto gained fame in his own lifetime.

The artist was commissioned for works in Florence, Naples, Milan, and Rome. A notable variation in medium is the c. 1300 CE Navicella mosaic (now much altered), a depiction of the boat of Saint Peter in his namesake basilica in the Vatican City. Other famous works include the frescoes in the Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence (1320s CE). The Bardi Chapel is a cycle on the life of Saint Francis of Assisi while the Peruzzi shows episodes from the life of Saint John the Evangelist.

Like other famed artists, Giotto often relied on assistants to complete his work or even transform his initial designs into reality, which he then signed. This has made identification of some works problematic, notably three altarpieces and, most controversial of all, the frescoes in the Upper Basilica at Assisi which may well have been supervised by the master but not actually painted by him. The frescoes show scenes from the life of Saint Francis of Assisi, and the debate still rages on today as to who painted them, principally perpetuated by the sheer quality of the scenes and the need by some historians to attribute them to a known master. Even though Giotto was in demand all across Italy, he did not live by his art alone and was something of a businessman, hiring out, for example, equipment needed for weaving. Other personal information we know is that Giotto was a lay member of the Franciscan order and he was famous for his wit.

Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

Giotto's most celebrated work today, completed when at the peak of his career, is considered to be the frescoes of the Scrovegni Chapel (aka Arena Chapel) in Padua, northern Italy. The chapel is named after the man who commissioned both it and the frescoes inside, Enrico Scrovegni, a wealthy banker in the city. Enrico's father was Reginaldo Scrovegni, an infamous moneylender (who made it into Dante's Inferno) and Enrico had followed a similar career path. It may be that Enrico invested in the chapel to make up for past sins and, if so, then it is no surprise that the building was dedicated to Santa Maria della Carita, the Virgin of Charity. The chapel was intended as a private family one, and it once stood next to an impressive palace but today that building has long gone, and only the chapel survives as an indicator of Scrovegni's ambition for immortality.

Giotto's frescoes, worked on from c. 1304 to c. 1315 CE, form a cycle of the lives of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ. There are 38 scenes in the chapel's interior which are divided into three rows on the side walls, a multiple sealed archway which leads to the altar and a single large scene on the entrance wall. The scenes should be read from the top row, the panel on the right as one enters, and then followed around the chapel before descending to the second row and again around and down to the third. The entire space measures 20.4 x 8.5 metres (67 x 28 ft.) and the height of the barrel vault ceiling is 18.5 metres (61 ft.). The side wall panels each measure 2 x 1.85 metres (6 ft. 6 in. x 6 ft. 1 in.). The viewer is, then, literally surrounded by Giotto's imagery, much of which has a deep blue background to match the starry night ceiling.

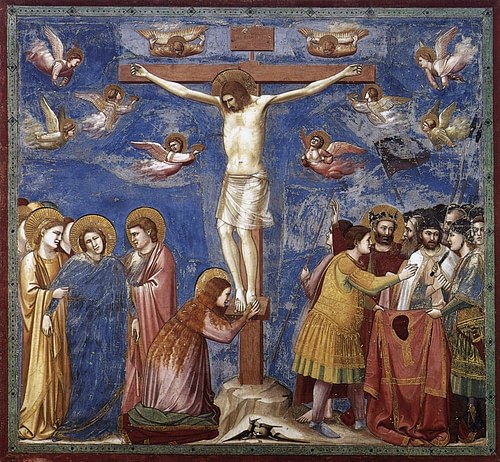

The Crucifixion panel is a typically busy Giotto scene with angels circling overhead, distressed onlookers on one side and disinterested ones, who argue over Jesus Christ's robe, on the other. The Nativity panel is a good example of Giotto's innovative achievement of depth in the scene with, for example, part of the arm of the shepherd hidden behind his fellow and the donkey twisting its head away from the viewer. Emotions are evident, particularly Mary's concern for her newborn baby and Joseph's weary face and posture, reminding of the trouble required to find a place for the night. Directly below, the Last Supper panel is another innovative treatment, this time showing Jesus and the 12 apostles all present but having five of them seated with their backs to the viewer who must look over their heads to see the figures at the other side of the table.

The panel showing the betrayal by Judas, known as the 'Kiss of Judas', is another masterpiece of intense action, as here summarised by the art historian J. T. Paoletti:

[Giotto] has dramatized the event in ways unimagined by earlier artists. The brilliant yellow cloak of Judas virtually obliterates the figure of Christ. Caught in a maelstrom of unrelenting stares, Judas and Christ stand nose to nose, Christ's searching and compassionate eyes undimmed by Judas' angry glare. Giotto uses stereotypical characterizations of good and evil in the scene, presenting Christ with handsome features and Judas with a brutish face. The psychological intensity of the event is heightened, at the left of the scene, by Peter's act of violence: cutting off the ear of the high priest servant. The compositional pairing of the right-facing Peter and Christ against the hooded figure and the heavily cloaked Judas powerfully plays violence and human emotion against divine acceptance of God's plan for redemption. (76)

Finally, the Last Judgement is the subject of the wall through which one enters and leaves the chapel, a last reminder perhaps of the dangerous worldly temptations one is likely to encounter after leaving the sanctity of the chapel. Christ sits majestic in the very centre and is flanked by a host of angels and the apostles. Below, on the left are those who will spend eternity with Christ while on the right, the damned are shown being eaten by a terrible monster personifying evil. Enrico Scrovegni is shown as a kneeling figure just above the doorway.

The finished chapel must have been favourably received as Giotto was commissioned to produce the frescos mentioned above in the chapels of Santa Croce in Florence. One of his last masterpieces was the Stefaneschi altarpiece, completed by the mid-1330s CE for Saint Peter's Basilica (old version) in Rome. The altarpiece is composed of three panels of tempera, the ensemble measuring 2.45 x 2 metres (8 ft. 8 in. x 7 ft. 2 in.). Scenes are painted on both sides of the piece and show episodes from the life of Saint Peter. Signed by Giotto but attributed to his workshop by some historians, the work is now in the Vatican's Pinacoteca.

Architectural Projects

Despite having no particular experience in architecture, Giotto was made the capomaestro (chief architect) of the ongoing project to build Florence's cathedral in 1334 CE. The appointment may simply have reflected Giotto's reputation as the foremost artist in the city but he did design the campanile (bell tower), even if the walls were later thickened to support the weight, amongst other design developments. Another architectural project was the elegant and multi-arched Carraia bridge in Florence, but this was destroyed in a Second World War bombing raid and never rebuilt.

Reputation & Legacy

During the High Renaissance, Giotto was recognised as being one of the movement's founding fathers for the skills he brought to painting described above. In addition, as the celebrated sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE) noted in his own c. 1450 CE autobiography, Giotto had helped to revive the arts in general by combining his talent (ingegno) with a sound knowledge of the doctrina (teachings) of the masters from antiquity, that is the ability to accurately and dramatically represent the proportions and anatomical details of the human body.

Giotto's reputation as the 'first Renaissance artist' was further enhanced by the favourable opinion of such figures as the poets Dante Alighieri (1265-1321 CE) and Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374 CE), and Giorgio Vasari. The artist even crops up in literature, notably in the work of Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375 CE), where he tells many funny stories. Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE), Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) and Raphael (1483-1520 CE) studied Giotto's work, continued his approach, and then added such new techniques as chiaroscuro (the contrasting use of light and shade) and mathematical perspective to their work. Giotto had begun these first steps into achieving a greater reality in art, and his shadow was so large over early Renaissance art that historians have labelled countless similar style artists as 'Giotteschi'.