During the Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE), the fight between Vitellius and Vespasian would ultimately bring about the demise of four legions, the XV Primigenia, I Germanica, IIII Macedonica, and XVI Gallia. All four of these legions had previously served the Roman Empire with distinction under such leaders as Pompey and Octavian but made what turned out to be the wrong choice in 69 CE. While there remains a question concerning the loyalty of XV Primigenia, three of the legions made the mistake of supporting Vitellius.

Roman Expansion

Originally, the Roman army consisted of a citizen-based militia recruited from the propertied citizens. However, the consulship of Gaius Marius (l. 157-86 BCE) brought a number of changes. Property ownership not being a requirement anymore, the Marian Reforms allowed the Roman army to reinvent itself as a professional fighting force. Another significant change came in the reorganization of the legion. The new legion was broken into centuries and cohorts. A centurion, commanded a century of 80 men (not 100) – six of these centuries equaled a cohort of 480 men. With the rebirth of the legion, the legionary became a well-trained and disciplined foot soldier, fighting as part of a well-organized unit.

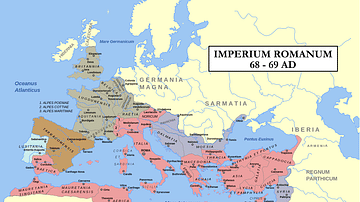

With Gnaeus Pompey’s (106-48 BCE) venture into Spain and Caesar’s assault on Gaul, the number of legions increased dramatically. As the empire expanded, more legions were necessary to keep the frontier borders secure. Before the time of the first Roman emperor Augustus (Octavian) (27 BCE - 14 CE), the Roman army was constantly on the march, relying on temporary camps more than permanent fortresses. As the borders of the empire expanded, permanent fortresses began to replace the marching camps. This move helped to stabilize the frontier.

After his successful return to Rome, Augustus wanted to be assured that his legionaries were loyal to him and not a usurper. Each soldier had to take an oath of allegiance to the Roman emperor, the ius iurandum: an oath renewed every year, on 3 January. Next, Augustus reduced the number of legions from 60 to 28. These 28 legions became 25 after the Roman commander Publius Quinctilius Varus (46 BCE - 9 CE) lost three legions - XVII, XVIII, and XIX - in the disastrous Battle of Teutoburg Forest. Most of the 25 legions were stationed in the troubled provinces and along the borders - only nine cohorts were assigned to Italy with three of these in Rome. In the end, Rome had a standing army of 150,000 legionaries and 180,000 auxiliary infantry and cavalry.

![Battle of Teutoburg Forest [Artist's Impression]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/750x750/2255.png?v=1713913143)

The empire’s expansion brought them into contact with a population of different customs, languages, and religions. To deal with this disparity and maintain the peace, the Pax Romana, the Romans relied on the army. According to historian Stephen Dando-Collins in his book Legions of Rome, the 1st and early 2nd century CE was the golden age of the legion when they "swept all before them." He considered the Roman legion of the imperial era to be "a triumph of organization.” He added, "… each component from heavy infantry to cavalry, artillery to supporting auxiliary light infantry, fitting neatly together to form a solid, self-contained military machine." (10)

Names, Numbers, & Emblems

There appears to be little consistency in the naming and numbering of various legions. It depended on when, where, and by whom the legion was formed. Some were named after a successful campaign – i.e. I Germanica or IIII Macedonica or, in the case of Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE), after his family - i.e. IV Flavia Felix. Before the Marian Reforms, each legion carried five standards: an eagle, horse, bull, wolf, and bear. Marius gave each legion one common standard, the silver (later gold) eagle. Since all legionaries wore the same uniform, to distinguish one from another, each legion adopted their own standard, birthstone, and emblem - all of which generated a sense of identity, unity, and pride within the individual legionary. With each legion having its own standard, there emerged new positions of great honor within the cohort. Among them were the vexillarius or bearer of the cavalry standard (vexillum), the signifier or bearer of the infantry standard (signum), the imaginifer or bearer of the emperor’s image, and, most importantly, the aquilifer, bearer of the golden eagle standard (aquila).

The emblem which adorned a legionary’s shield was often either an animal (bull and boar) or a bird (eagle). Many of the legions, such as IIII Macedonica, that used the bull as its emblem originated in Spain under Pompey, not Caesar as some believe. Unique emblems were V Alaudae’s elephant, XIV Gemina Martia’s eagle wings, III Italica’s stork, or XVI Gallica’s lion; other emblems were mythological in nature such as II Parthica’s Centaur, II Augusta’s Pegasus, XXII Fulminata’s Mars’ thunderbolt, or XI Claudia’s Neptune’s trident. A legion’s birth sign represented the month in which it was organized. Since many of the legions were founded in the winter months when they remained in camp, Capricorn was a common birth sign although Gemini, Aries, Taurus, and Cancer appear. With the changes made within the legion from the time of Gaius Marius through the imperial era, the Roman military remained a feared adversary for all who challenged it. This challenge became very real in one of the most crucial areas of the empire: the Rhine.

The Rhine Corridor

Gaul was conquered by the legions of Julius Caesar in the Gallic Wars and, according to Nigel Pollard’s The Complete Roman Legions, quickly assimilated into the Roman Empire. Between 58 and 51 BCE, Roman legions pushed the borders of the Roman Empire’s frontier to the banks of the Rhine River. Augustus divided the region into three provinces: Gallia Aquitania, Gallia Lugdunensis, and Gallia Belgica (the Rhine frontier). Augustus’s stepson Drusus Julius Caesar (14 BCE - 48 CE) split the Rhine corridor into two separate zones: Germania Inferior (Lower Germany) and Germania Superior (Upper Germany). However, despite Rome’s best efforts, the territory remained unstable.

This corridor would remain a place of conflict for years to come - an area which prompted Augustus and those who followed to concentrate a significant number of legions throughout the provinces. In 9 CE, the area was the sight of one of Rome’s worse military disasters: the Battle of Teutoburg Forest and the famed lost legions. Decades later, the Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE) proved to be a contentious time along the Rhine. It would see both a maligned Roman commander named Julius Civilis lead the Batavian Revolt as well as a near civil war that threatened the foundations of the empire: a battle between two claimants to the throne - Vitellius and Vespasian.

The Year of the Four Emperors

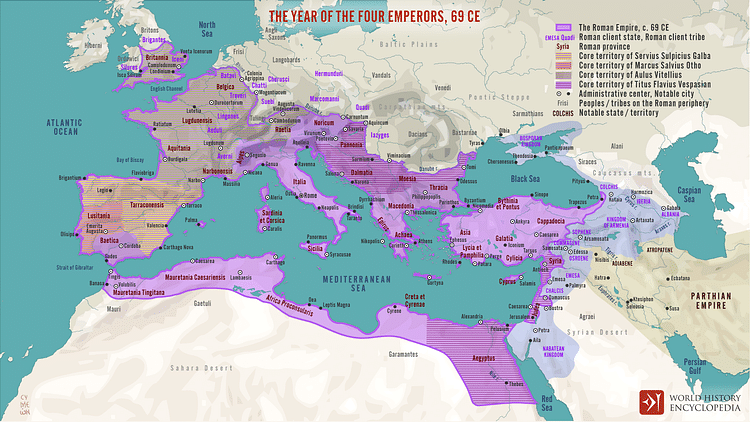

By 68 CE, the fire of 64 CE, the supposed conspiracies, the numerous insurrections, and an empty treasury finally led to Nero's (r. 54-68 CE) downfall. The Roman Senate declared him an enemy of the public and named Servius Galba, the governor of Spain, as the new emperor. Realizing his days as emperor were over, Nero attempted suicide but failed, needing help to take his own life. The aged Galba (r. 68-69 CE) became emperor but failed to name fellow governor Marcus Otho as his rightful successor.

With the support of the military, Otho bribed the Praetorian Guard who murdered Galba in the Roman Forum. Otho was proclaimed emperor in January 69 CE. However, Otho, like Galba, would not stay in power very long. His defeat and suicide following the Battle of Bedriacum would be the catalyst for a bitter civil war. Germanic-based legions refused to take an oath of allegiance to him, throwing their support behind the governor of Germania Inferior, Aulus Vitellius. However, in the East, the legions of Asia Minor and the Balkans chose to support the governor of Syria Titus Flavius Vespasianus (Vespasian). Before the year was out, a civil war erupted, pitting the legions of Vitellius against the legions of Vespasian. A second battle at Bedriacum would bring the defeat and death of Vitellius and the ascension of Vespasian to the throne. Taking advantage of the situation, Civilis urged his fellow Batavians to rise up against the Romans.

The Batavian Revolt

Like many Roman provinces, Batavia supplied Rome with auxiliary troops - even the emperor’s personal bodyguard - in exchange for tax exemption. In 66 CE, Civilis, who served as a Roman auxiliary officer, and his brother were arrested and charged with treason by the governor of Germania Inferior. Although the charges were false, Civilis’ brother was executed, while he remained in Rome until he was finally released by Galba in 68 CE. Upon Civilis' return home, the new governor, Vitellius, demanded his arrest and execution, but he needed the Batavians to supply troops in his battle against Otho and had to drop all charges.

Upon realizing the seriousness of Vespasian’s challenge to the throne, Vitellius demanded more Batavians to be conscripted into the army; however, the demands far exceeded the maximum agreed upon in their treaty with Rome. With the possibility of a war between Vitellius and Vespasian apparent, Civilis led his fellow Batavians into a revolt. His animosity towards Vitellius brought him into the camp of Vespasian - at least in appearance. While Civilis waged his own private war with Rome, the fight between the warring emperors would ultimately bring about the demise of four legions.

The Demise of the Four Legions

The exact origin and history of Legio I Germanica (emblem: possibly a lion; birth sign: Capricorn) are unclear. Some sources claim it was founded by Caesar while others maintain it was Pompey‘s elite force. Stephen Dando-Collins in his Legions of Rome states the legion fought against Caesar at Pharsalus, Thapsus, and Munda. It may have temporarily been assigned the name Augusta for its praiseworthy service but was stripped of the title by Marcus Agrippa (63 -12 BCE) for cowardice. It may even have been disbanded and then reformed. However, there is sufficient evidence to show that it was with Octavian in his battle against Mark Antony (83-30 BCE). The legion also fought with the future emperor in the battles of Mutina (43 BCE), Philippi (42 BCE), and in the campaign against Sextus Pompey (36 BCE).

From 6 CE, the legion was stationed on the Rhine frontier, remaining there until 69 CE. During this time, it acquired its cognomen Germanica after serving with Germanicus at the Battle of Long Bridges in 15 CE. In 67 CE, the legion participated in the defeat of the rebellious Gaius Vindex (25-68 CE), governor of Gaul, who supported Galba’s claim to the throne against Nero. However, after Galba became emperor, I Germanica’s commander Fabius Valens (d. 69 CE) pledged his support for Vitellius. Later, he led his legion to victory against Emperor Otho in the First Battle of Bedriacum in northern Italy.

The legion’s demise is as uncertain as is its origin. According to Pollard, the legionaries were defeated at the Second Battle of Bedriacum in 70 CE by Vespasian’s army and were eventually disbanded. However, Dando-Collins claims that several cohorts of I Germanica that had remained on the Rhine - the cohorts in Italy had already surrendered - defected to Vespasian and participated in the defeat of the rebels at the Battle of Old Camp. Vespasian was not impressed by the defection and disbanded the legion.

Legio IIII Macedonica (emblem: bull; birth sign: Capricorn) was formed by Pompey the Great (although Pollard claims it was Caesar), and by 44 BCE, it was stationed in Macedonia where it received its cognomen. The legion returned to Italy with three other legions. Mark Antony intended to send them to Cisalpine Gaul where he was to serve as governor; however, while on the march northward, the legion defected to Octavian and helped him defeat both Antony at Mutina and the assassins Brutus and Cassius at Philippi. Collins states the legion was partially destroyed at Philippi but survived and was rebuilt. They may have participated in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE against Antony and in Augustus’ Cantabrian wars (29-19 BCE). They were stationed in Spain until 43 CE when they were reorganized by Claudius (r. 41-54 CE) and stationed in Germania Superior until 70 CE, replacing XIV Gemina who participated in the invasion of Britain.

During the civil war, along with XXII Primigenia, the legion sided with Vitellius against both Galba and Otho and joined Vitellius’ march into Italy, participating in the First Battle of Bedriacum. According to Dando-Collins, several of the legion’s cohorts fought with Vitellius at Bedriacum and in the Battle of Cremona but lost both and surrendered. The cohorts remaining on the Rhine joined in the Civilis revolt. Because of this, they were disbanded by Vespasian but reformed as the 4th Flavia Felix.

The short-lived Legio XV Primigenia (emblem: possibly wheel of fortune; birth sign: Capricorn) was named for the goddess of fortune Fortuna Primigenia and founded by Emperor Caligula (37-41 CE) along with XXII Primigenia in 39 CE in preparation for his invasion of Britain. After the failed invasion, the legion was stationed on the Upper Rhine, relocating to the Lower Rhine around 46 CE. A detachment of the legion may have served with Vitellius in Italy while the remaining legionaries were stationed at Vetera, having replaced XXI Rapax. Civilis attacked the fort, planning on starving them into submission.

The situation at the fort was desperate. With food supplies nearly exhausted and no sign of relief, the commander had little choice but to swear allegiance to the Gallic Empire and surrender. The legions of V Alaudae (some of its cohorts were in Italy with Vitellius) and XV Primigenia marched out of the fort under terms of safe passage, but as the unarmed legionaries left the camp they were besieged by Civilis' forces and massacred. Although a handful was able to return to the fort, Civilis set the fort on fire, killing all those inside - a total of 4,000 died in the attack. The legion was disbanded by Vespasian.

Like other legions, Legio XVI Gallica made a poor choice, choosing to support Vitellius. The legion (emblem: boar or lion; birth sign: Capricorn) was founded in 49 BCE by Caesar although Pollard asserts it was formed by his stepson Octavian before the Battle of Actium. In 16 BCE, the legion served under Drusus Caesar on the Rhine (where it received its name Gallica), remaining there until it was disbanded by Vespasian in 70 CE. During the reign of Nero, it was moved to the Lower Rhine. In January 69 CE, it was reluctant to support Galba and swore allegiance to Vitellius, aiding in the defeat of Otho. While in Rome, some of the legionaries supposedly became members of the Praetorian Guard. According to Dando-Collins, caught up in the Civilis revolt, the legion deserted their general Gallus and surrendered to Civilis’ forces. Gallus was later executed. Vespasian was appalled and abolished the legion. It was reformed as XVI Flavia.

Conclusion

Despite a somewhat inglorious ending, the legionaries exemplified what a good soldier should be and had previously served the empire well. However, during the Year of the Four Emperors, they made the ill-fated choice to support Vitellius against the other candidates for the Roman throne. Had Vitellius won, history would be praising them for their valor and fortitude. Unfortunately, they made a fatal mistake. All four, although Primigenia was reformed, met their demise and are relegated to the forgotten and dishonored legions of the Roman Empire.