As a superpower in its own right and in competition with Rome, Parthia's empire - ruling from 247 BCE to 224 CE - stretched between the Mediterranean in the west to India in the east. Not only did the Parthians win battles against Rome they were also successful commercial competitors. On the military front, as part of their original expansion, Parthia's victories against the Seleucid Empire would include the defeat of Antiochus VII by Phraates II at the Battle of Ecbatana in 129 BCE and the expansion and consolidation of their empire through the military campaigns of Mithridates I (r. 171-132 BCE) and Mithridates II (r. 124-88 BCE), but perhaps their greatest victories were against Rome.

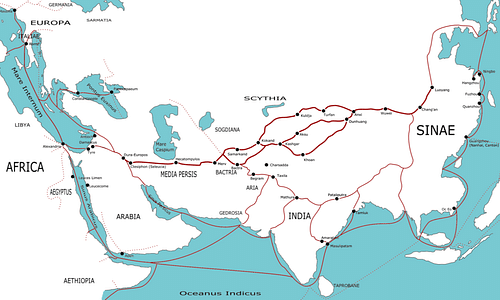

While in control of the eastern trade routes by way of the Red Sea and overland routes through Arabia, Rome wanted to expand its interests to include the lucrative Silk Road through Mesopotamia. There was only one problem; Parthia was in the way. Mesopotamia was theirs, and Parthia would prove capable in defending its interests. After Crassus' defeat at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE and Mark Antony's retreat from Media in 36 BCE, a peace agreement was reached with Rome in 20 BCE. With peace obtained and its silk routes protected, Parthia could now go on to successfully compete with Rome through trade.

Parthia Emerges

The story of Parthia begins with Alexander the Great. Son of Phillip II of Macedon, he and his father adopted the best military techniques and weaponry of their time. With an unstoppable desire to conquer, Alexander took those techniques and led his soldiers on a remarkable foray into other lands. Conquering Egypt, Persia, Syria, and Mesopotamia, he even established footholds in India. After his untimely death at the age of 32, his generals divvied up the areas taken over. Ptolemy I took over Egypt, establishing the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Seleucus I Nicator took the region of Mesopotamia and other districts once central to Persia, creating the Seleucid Empire. Incorporating Greek infrastructure and administrators, Seleucus adopted Persia's form of governance. With districts or satrapies headed by satraps (governors) beholden to a central government and ultimately the king, Parthia became one of those satrapies.

The Parthian satrapy was located east of the Caspian Sea. Thought to be related to the Scythians of Central Asia, the nomadic Parni tribe eventually came to control Parthia. With the Seleucids weakened by internal war and conflict with the Ptolemies in the west, the Parni made their move from Parthia in the east. With Mithridates I conquering, and Mithridates II expanding and consolidating, the Parni (now called the Parthians) conquered much of the area once held by the Seleucid Greeks. Most importantly - central to former Babylonian, Persian, and Seleucid interests - the Parthians took over the all-important Fertile Crescent area of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers known as Mesopotamia. Adding to their sphere of influence, at their western boundary, the Parthians also took Armenia from Rome. In the east, they added the vassal kingdom of Characene. To the south, as part of their overall expansion, they took control of Elymais and the important city of Susa.

Parthia's Conflict with Rome: A Stalemate

With Rome's indomitable desire to ever widen its reach, it was Parthia that stood in the way of the eastern expansion of the Romans. However, Parthia was able to do more than hold its ground. With a unique hit-and-run fighting style, Parthian military campaigns and their style of warfare (including pretending retreat) were well suited to counter the concentrated troop movements of the Roman army. With archers on the fleetest of horses, and camel riders providing a steady supply of arrows, they made sitting ducks of infantry unable to engage except at close range. When Rome's cavalry gave chase, the Parthians had an answer. So adept at their lethal craft, they developed the 'Parthian shot.' Able to shoot backward at full gallop, the Parthian archer delivered kill shots at pursuing cavalry. In this way Parthian horsemen were able to come at enemy troops from all directions, creating confusion and wreaking havoc. Finally, their heavy-armored horse cavalry (cataphracts) provided offensive support and assisted in mopping up remaining pockets of resistance with long lances and swords.

Strategically, Parthia was also able to expand, then capitalize on the Roman Republic's other conflicts. It was during Rome's costly war with Carthage - the Punic Wars between 264 and 146 BCE, when Hannibal did such damage on Roman soil - that Parthia's ascendancy began in 247 BCE. During the Gallic Wars between 58 and 51 BCE, Crassus invaded Parthia and was utterly defeated at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE. There the Roman standards were taken; a huge psychological blow for Rome. With the ultimate goal of conquering the Parthian capital Ecbatana, Mark Antony took over Armenia, and from there invaded Media. Antony's attempt on Parthia ended in a disastrous retreat from Media in 36 BCE and Roman withdrawal from Armenia in 32 BCE. This left Armenia, an important buffer state, in the hands of the Parthians. Thus, though it lost some important battles to the Roman commander, Ventidius, in 39 and 38 BCE and was later invaded by Trajan in 115 CE, Parthia proved it could not only win battles against Rome but it also gained territory.

With a costly civil war just ended, when Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) defeated Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, Rome was ready to sue for peace. Still, Rome did not come to the negotiating table with a weak hand. Because of Rome's substantial geographical presence and reputation that though it might lose battles, it won wars, it appears both sides realized little progress could be made against the other's sphere of influence. Therefore, to avoid a continuation of a conflict that would significantly weaken footholds already gained by each side, a treaty was made allowing Parthia to eye gains toward the east and Rome to increase and solidify gains made in the west. As Raoul McLaughlin aptly states:

In 20 BCE Augustus secured a long-term peace agreement with the Parthian King Phraates IV. This agreement allowed both rulers to concentrate their military activities on other frontiers and thereby enlarge their respective empires. (181)

Commercial Competition

Considering Parthia's geographical presence and that it would be a longtime competitor of Rome in its own right, any study of ancient Middle Eastern economy during Roman times should take into consideration the possibility that Rome's commercial expansion in the area was to counteract Parthian influence. Parthia did indeed control the overland silk roads through Mesopotamia. As Richard Frye mentions,

The small states in the Fertile Crescent, which favored the decentralized 'feudal' form of government of Parthia, developed greatly as mercantile centers of international trade. The first two centuries of our era was an age of commerce, and the oasis states of the 'Fertile Crescent' flourished as never previously. (Curtis, 18)

Rome's counteraction to Parthia's presence and jurisdiction of the silk routes through Mesopotamia was to control the southern east-west land routes through Arabia and sea routes by way of the Red Sea. From Rome's point of view, with the recent conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE and control of Anatolia nearly complete in 25 BCE, then with peace in 20 BCE, Rome could now expand its interests, this time commercially.

Rome sought to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean region with the help of client kings. Eyeing Egyptian and African markets and the crucial eastern trade routes through Arabia and the Red Sea, Rome had Herod the Great to build the city of Caesarea on the southeastern coast of the Mediterranean in 20-10 BCE. Augustus then granted the vital city of Gaza (just south of Caesarea) to Herod. The products of southern Arabia traveled by camel to Gaza and farther, to ports in Phoenicia. As one of those ports, Caesarea was well situated to receive those goods, in addition to products coming up from the Red Sea. From Ethiopia and Somalia in Africa and from Yemen and the Hadramaut in southern Arabia came frankincense and myrrh. From the northeast coast of Africa, as far south at Cape Guardafui, came ivory and tortoiseshell. Goods like silks, decorated cotton; and spices like pepper, cinnamon, and cassia - coming from India, Indonesia, and Southern China - also arrived by way of the Red Sea. As Robert Tomber mentions, “In the complex network of regions it is the Red Sea that served as a funnel for goods from the East to the Roman Empire” (57).

Moreover, when Trajan took over Petra (inland, east from Gaza and Caesarea) in 106 CE, Rome now not only controlled Gaza's markets but it captured lucrative eastern trade flows from Petra with its location en route to Gaza. As Gary Young points out, incense was carried from Petra by road to Gaza (97). By establishing Caesarea and owning Petra and Gaza with its diverse markets, Rome was in a position to not only dominate Mediterranean commerce and eastern trade flows but also overland trade to consumer cities in the southeastern Mediterranean region, like Bostra, Samaria, and Jerusalem.

The Silk Routes Parthia Came to Dominate

On Parthia's end, the development of trade with the east started with the infrastructure they inherited from the Seleucids. It wisely preserved the cities, lands, and roads it received. Their possession of Armenia and possible access to the Black Sea and control of Hyrcania and the Caspian Sea gave them access to Central Asian markets. Their takeover of Persis and cities like Antioch-in-Persis on the Persian Gulf meant access to Indian markets by way of water. Their control of Elymais and the politically important city of Susa, and the fertile region of Media and its wealthy city Ecbatana would have enriched the Parthians culturally and materially, but one of Parthia's most prized processions would have been the Royal Road.

Running east and west through Mesopotamia, the Royal Road solidified Parthia's position as an international trader. With it came Bagdad and Seleucia as gateways to the west; then stretching east to include Bactria, a neighbor of India, access to eastern markets were now direct and lucrative. Products like nard, costus, cinnamon, ginger, and pepper, came to the Mediterranean by the overland caravan route through northwest India, Afghanistan, and Iran to Seleucia near modern-day Baghdad, where it followed routes along the Tigris and Euphrates to northern Mesopotamia. From there it split west to Antioch or on to Asia Minor to reach the sea at Ephesus. Another route involved loading ships at India's northwest ports which coasted west then turning up the Persian Gulf to unload at its head. From here camels took the merchandise to Seleucia. These were all countries, cities, districts, or trade routes, that Parthia in its heyday, either traded with or controlled.

In addition, trade with China was a real possibility. According to Wang Tao, "We now know that, as early as the third millennium BCE, a network [of roads] already existed in the Eurasian steppe land, stretching from the Caspian Sea in the west, to the Tarim Basin in the east" (87). With the expansionist policy of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), contact with the west was made. According to Chinese chroniclers, Chinese envoys were sent to Parthia in 115 BCE. The exchange of token trade items between the Parthian king and the Chinese representatives may have set a precedent for broader trade deals in the future. We do know that remains at a Parthian tomb at Palmyra, erected during the first three centuries CE, were covered with costly clothing from China and India.

Conclusion

As a competitor of Rome, the strength of the Parthian military was sticking to a strategy of picking their fights carefully: on open ground that favored their heavy cavalry and Parthian horse archers. Their use of ambush also served them well, but the Roman use of shields and swords, in close interlocked formation, made the Roman army an immovable force difficult to reckon with. When both sides stuck to their tactics, success was usually the outcome. With significant successes and losses by each side, the war between Rome and Parthia is generally agreed to have been a stalemate. This gave Parthia the distinction of being the only force Rome, in its ascendancy, could not defeat. Parthia also competed with similar success when it came to commercial activity. While Rome over time garnered the southern trade routes in the Middle East, Parthia controlled the northern trade routes through Mesopotamia. As Parthia consolidated its empire reaching to China and India, markets and trade routes were opened to include central Asia and trade through the Persian Gulf. The end result was, the wealth that came its way through trade, helped Parthia hold its empire together, making it, at its zenith - militarily and commercially - Rome's ablest competitor.