The wearing of cosmetics and perfumes by both men and women goes back a very long way indeed as the ancients were just as keen as anyone to improve their appearance as quickly and as easily as possible using all manner of powders, creams, lotions, and liquids. Written and pictorial records combine with remains of the materials themselves to reveal how the ancients not only improved their looks and smell but also tried to cure such irritating challenges to one's vanity as baldness, grey hairs and wrinkles. In many ancient cultures, cosmetics and perfumes also had a close connection with religion and rituals, especially the burial of the dead.

Egyptian Cosmetics

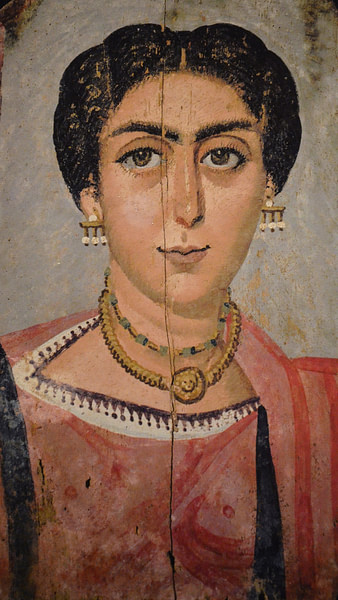

The ancient Egyptians were big on cleanliness and appearance as the purity of the body and soul had religious implications. This then was a culture where both men and women of all classes were keen to look their best, even when they died. In addition, the Egyptians made a clear link between cosmetics and the divine. For example, priests during religious rituals often anointed statues of gods with scented oils and even applied make-up to them. Such was the demand for these cosmetic products some temples produced their own, notably at Karnak where scented oil was manufactured and wall inscriptions show several different recipes.

Another indication of the importance of cosmetics to the Egyptians was their inclusion in those goods traded internationally along with finely carved examples of the common tools for their application. Such items are sometimes listed in surviving records like the 14th-century BCE Amarna Letters. Another important source of information on ancient Mediterranean cosmetics has been the Uluburun shipwreck (1330-1300 BCE) which had in its varied cargo many plants and resins which would have been used to produce perfumes. Finally, there are visual records which clearly show the colours and on which parts of the face, in particular, make-up was applied. There are even depictions in art of people applying cosmetics such as a young woman applying paint to her lips (while engaging in rather more acrobatic sexual activities) in the 12th-century BCE Turin 'Erotic' papyrus.

Cosmetics were prepared in ancient Egypt using a wide range of materials. The eyeliner and eye shadow so famously worn by such figures as Tutankhamun and Nefertiti was made by grinding minerals like green malachite and black galena. The slate palettes used to create the paste have been found in many tombs dating right back to the Predynastic Period (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE). Another cosmetic not uncommon in graves is a red ochre and vegetable mix used for blushing the cheeks - its use in practice can be seen on portraits of Queen Nefertari (d. c. 1255 BCE) on the walls of her tomb. Cosmetics were not only for beautifying, but some had a medicinal value such as moisturisers made from fats and oils or those lotions and unctions using natron and ash which were intended to cleanse the skin. Research on the lead-based eye paint so beloved by the Egyptians has revealed that it has a definite effect on the body's immune system and both reduces the effects and risk of many eye complaints. Finally, there were other cosmetic applications which had more ambitious effects like pastes to repel insects, cure baldness, reverse greying hair or smooth out wrinkles.

Cosmetics and perfumes were often an expensive item to produce, and their ingredients could be difficult to obtain. Perhaps the most famous such luxury substance is frankincense. Obtained as a fragrant resin from various Boswellia trees, frankincense was used not only as a perfume for the living and the embalmed dead but to disguise bad breath, enrich the skin and hair, and as a massage oil. A second famously expensive substance is myrrh, a resin from the bush of the same name. Myrrh was used as a perfume, in cosmetics, and in medicines, and was only available in antiquity from Yemen and Somalia - hence Queen Hatshepsut's expedition to the Land of Punt in the mid-15th century BCE to grab some myrrh trees and plant them, amongst other exotica, at the temple of Deir el-Bahari. Due to their high value, such items as frankincense and myrrh became important trading commodities across the ancient world.

A better survivor than the cosmetics themselves are the containers used for make-up which range from simple reed tubes to finely-crafted vessels made from coloured glass (women and fish were a common shape), faience, and stone (especially alabaster). For those who could afford it, their collection of cosmetics was kept in a wooden chest along with other personal essentials like a mirror (made from highly polished metal), razor, and tweezers. Not for nothing then was the painted eye symbol one of the components for the Egyptian hieroglyph for beauty.

Greek Cosmetics

Like the Egyptians, the Greeks were partial to a bit of make-up and, indeed, it is their word kosmetika which gives us our 'cosmetics.' The Greek term had a rather different application as it really referred to those preparations which protected hair, face, and teeth. The term for beautifying make-up was to kommotikon. Greek perfumes, meanwhile are known to have been in use since at least the Middle Bronze Age (14th-13th century BCE) and are first mentioned in literature in the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer, written in the 8th century BCE. All manner of plants, flowers, spices, and fragrant woods from myrrh to oregano were infused in oil. As oil was used as the base (today it is alcohol), most perfumes were a thick paste and so a special fine spoon-like implement was needed to extract it from the small bottles it was kept in. As with cosmetics, perfumes were used for pleasure, seduction, as a status symbol and in rituals (especially burial).

Rouge for the cheeks, whitener to make the skin paler and black eyeliner and eye shadow were all used by Greek women. Men, with the exception of some men who played the passive role in homosexual relationships, did not wear make-up. Hair dye may have been used by both sexes, and there were two basic types: one made hair darker and used such dyes as those extracted from leeches left to rot in wine for 40 days and the other type made hair lighter and used a mixture which contained beechwood ash and goat fat.

Rouge was made from red ochre as in Egypt or from a dye extracted from a type of lichen. Eyeliner and eyebrow paint was made from a kohl powder which contained soot, antimony, saffron or ash. Ash of all kinds was seen as a terribly useful substance and was used to clean teeth. As nowadays, it seems that the more exotic the ingredients of a cosmetic were, the more likely it was to succeed. Thus such weird and wonderful substances as snail ash was applied to remove freckles, grease from sheep's wool was made into a face cream, and the excrement of lizards was rubbed into skin blemishes and wrinkles.

Some Greek writers did begin to moralise that cosmetics were somehow a trick that only lower-class women or prostitutes would employ, but this did not seem to stop women of all classes, single or married, from using them in practice. Finally, as in Egypt, the Greeks often kept their best cosmetics and perfumes to accompany the dead in their tombs. Lekythoi, the slim one-handled jugs used for storing fine oils and perfumes were especially dedicated to the deceased and are often decorated with themes related to burial and travelling to the next life. Other common grave goods include the circular lidded box known as a pyxis which was a typical storage place for cosmetics while the squat alabastron was a favourite for creams and unguents in Minoan, Mycenaean, and Classical Greece.

Etruscan Cosmetics

The Etruscans provided, in many ways, a cultural bridge between the Greeks and Romans, and the use of cosmetics and perfumes is just one more example. At first, Greek cosmetics were directly imported from such places as Samos, Corinth, and Rhodes, but then, using tried and tested Greek recipes, the Etruscans began to import ingredients from the Near East to locally manufacture lotions and potions to beautify their bodies and use in religious rituals. Tombs have revealed many small containers and spiky glass bottles used to store unguents, pastes, and oils. Delicate tools to extract the cosmetics from such small vessels are also abundant and often have finely carved figures of women at the end of their handles. The use of such tools can be seen in some of the scenes carved on the backs of Etruscan bronze mirrors.

Roman Cosmetics

In the Roman world, cosmetics was a preoccupation of women, not men, and any man spending too much time on his appearance was often ridiculed. A famous example is Emperor Otho (r. 69 CE), who was criticised for shaving daily and then applying a face pack of dough. As in the Greek world, some Roman writers - all male - did regard make-up as the concern of prostitutes or unfaithful married women trying to catch a lover, but, as with the Greeks, it seems from art, artefacts, and references in literature that, broadly speaking, Roman women of all classes carried on the make-up traditions of their Greek predecessors.

Perfumes were another widely used substance in the Roman world and were used for all manner of effects from adding a twist to the taste of wine to making public baths a more pleasant environment to pass the time in. Common perfume ingredients included the use of cinnamon, date palm, quince, basil, wormwood, and all manner of flowers from iris to roses.

All of these habits using cosmetics and perfumes are not only evidenced in literature and art but also in the thousands of small glass bottles, pottery jars and boxes found in archaeological excavations across the Roman world. One particular find from London is of interest, a bar brooch from which hang five miniature bronze implements: an ear scoop, nail cleaner, tweezers, and two cosmetic applicators.

Naturally, the Romans did achieve a few developments in cosmetics, just as they did in other areas. For example, the Romans considered asses milk a perfect skin softener. The most famous fan of the milk was Poppaea, the wife of Emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE), who bathed daily, a habit which required the maintenance of 500 asses. Fortunately, Roman writers were not too snobby to devote a great number of their pages to cosmetics, especially those with a possible health benefit. Ovid (43 BCE - 17 CE), for example, details a face pack with a bird's nest ingredient that he considered useful for a healthy complexion. The ingredients of another face cream he lists as follows: eggs, barley, gum, narcissus bulbs, honey, ground vetch, wheat flour, and powdered antlers. Another concoction, this one aimed at whitening the skin used white lead shavings which had been dissolved in vinegar and then left to dry. This was then mixed with chalk using more vinegar in order to make a handy cake. The ancients well-knew that white lead is poisonous (indeed they used it as a poison) and rather than ignorance, the use of such materials illustrates a flexible approach to ingredients which often produced preparations with a multitude of purposes.

Byzantine Cosmetics

In Late Antiquity, the Byzantines continued the earlier traditions mentioned above, and both men and women are recorded as using hair dyes (a boy's urine was thought to work wonders here), preparations for removing hair, and lotions to moisturise the skin. Women used to whiten their faces, paint their lips, and outline their eyes just as their counterparts in the earlier western Roman Empire had done for centuries. There were, too, anti-wrinkle creams, hair strengtheners, eyebrow stainers, and perfumes.

Such was their preoccupation with appearance that the Byzantines gained something of an unjust reputation in western Europe as pleasure-loving dandies, although Byzantine Christian preachers were known to admonish their flock for their vanity on occasion. As with previous cultures, one of the best indicators of the widespread use of cosmetics is the many surviving crucibles, containers, applicators, and spoons used to make, keep, and apply them. Both the Byzantines and Romans of Late Antiquity, being rather flashy in their taste for bling, often kept cosmetics in exquisitely made caskets of which one of the finest examples is the Muse Casket of the Esquiline Treasure. Discovered in 1793 CE in Rome and dating to the 4th century CE, the scalloped silver casket is decorated with engraved images of the Muses and contains five recipients for unguents and perfumes.

Recreating the Past

As experimental archaeology goes from strength to strength, and with the help of technology, more and more scholars are investigating just what the ancients put into their cosmetics and perfumes and have even tried to recreate some of them. One of the pioneers of this approach was the Italian chemist Giuseppe Donato in the 1970s CE, and some fragrances he examined have even been produced commercially such as the Donato and Seefried's Cleopatra perfume reportedly based on one worn by the Egyptian queen, who herself wrote a book on the subject of cosmetics. There has also been research into the effectiveness of some of the ancient cosmetics which claimed to remedy problems like wrinkles with some modern experts approving of the use of certain natural ingredients which did very likely make them effective or, at least as effective as any modern equivalent.