Art made by Scandinavians during the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE) mostly encompassed the decoration of functional objects made of wood, metal, stone, textile and other materials with relief carvings, engravings of animal shapes and abstract patterns. The motif of the stylised animal ('zoomorphic' art) – Viking Age art's most popular motif – stems from a tradition that existed across north-western Europe from as early as the 4th century CE, but which developed in Scandinavia into a confident native style by the end of the 7th century CE. Often, these animals twist and churn across their surface – imagine decorated carts, engraved jewellery and weapons, wall-tapestries and memorial stones – interwoven with other animals and plant ornamentation.

Narrative art of the region that tells an actual story is found in only a few instances before the last stage of the Viking Age, such as on the rare tapestries that have evaded being unravelled by the passage of time, and on the picture stones found on the island of Gotland in present-day Sweden. Besides the many different carved surfaces, some instances of more properly 3D-art are also preserved, mostly in the form of animal heads that were used to adorn posts, carts or caskets.

Several succeeding and sometimes overlapping styles have been identified within Viking Age decorative art, usually named after the finding place of a famous example of that style, such as:

- Style E (late 8th century CE-late 9th century CE). Important finds from Broa (Gotland, Sweden) and the Oseberg ship burial (Norway); long animal bodies; small heads in profile with bulging eyes; 'gripping-beasts' with muscular bodies and claws gripping everything nearby.

- The Borre Style (c. 850-late 10th century CE). Ribbon plait ('ring-chain', a symmetrical interlaced pattern); a single gripping-beast with triangular head and contorted body; most widespread of all the styles, found throughout Scandinavia and across the Viking colonies.

- The Jelling Style (just before 900-end of the 10th century CE). Beast with a ribbon-like body; head seen in profile; usually double-contoured body which is beaded; closely related to and overlapping with the Borre style.

- The Mammen Style (c. 950-1000 CE). Great, fighting beasts; spiral-shaped shoulders and hips; often asymmetrical; vigorous and dynamic; ribbon- and plant elements.

- The Ringerike Style (c. 990-1050 CE). Large animal in dynamic pose; movement; powerful and elegant; plant ornament; popular in England and especially Ireland.

- The Urnes Style (c. 1040-at least 1100 CE). Also named 'runestone style'; very elegant; asymmetrical; motif of the great beast; interweaving, looped snakes and tendrils; very popular in Ireland.

It must be said that although wood and textile must have been prime vehicles for Viking Age art, their often more expensive counterparts in metal and stone do better at surviving, causing a bias in our source material.

Purpose

Rather than creating art specifically for art's sake, Viking Age Scandinavians almost exclusively made applied art; everyday objects were jazzed up to make them more pleasing to look at. The rarer pictorial art often seems to match known stories about Norse mythology, depicting such scenes as a Valkyrie welcoming a warrior into Valhalla or Sigurd the Dragonslayer's story. As Anne-Sofie Gräslund explains:

Religion permeated life in the Viking Age and was especially important in Viking art. Artists and craftsmen certainly would have been important people because (…) art was generally created not for its own sake but as a mark of social prestige, often commissioned by the upper levels of society. Even though much of its meaning is lost to us, we can be confident of our interpretations at least in cases where myths known from Old Norse literature can be identified. Elements of Viking mythology are present in artistic ornamentation, and that religious content would have been obvious to contemporary viewers. (Fitzhugh & Ward, 62).

Both Viking art's link with the higher levels of society and with religion may help explain why the Viking Age art styles were (for the most part) common across Scandinavia throughout all levels of society. Copying was also standard-practice, which is not so odd considering Viking art's decorative purpose.

Materials & Techniques

Viking Age art's favoured materials were mostly things that could be carved or engraved: wood, stone, metal, but also such things as bone and amber. Textile, leather or cloth, for instance in the shape of colourful wall tapestries adorned with pictorial scenes, were also commonly used, although along with wood they are rather bad at standing the test of time. The bulk of material we can actually study thus consists mainly of decorated jewellery or metal utility goods such as horse equipment, as well as weapons and the lively, large memorial stones found in abundance across mainly Sweden and the island of Gotland. The carved wood that has survived, however, is spectacular and stems from such finds as the Oseberg ship burial (c. 834 CE) which was richly furnished with among others a beautifully carved wooden cart and three splendid sleighs, as well as five iconic 3D carved animal-head posts. These rare finds vividly demonstrate what we are missing out on.

The techniques that were used in Viking Age art were mainly those of relief carving or engraving and the use of contrasting materials and colours, with filigree and granulation being popular. A piece of jewellery, for instance, could be made of gilded bronze but decorated with silver. Traces of paint have frequently been found on the larger wooden- and stone objects, too, betraying that these once popped with vibrant shades of black, white and red, although yellow, blue, green and brown were also used.

Origins & Early Developments

The roots of Viking Age ornamentation mainly lie in a broader European Germanic tradition which was utterly smitten with animal ornamentation and was popular through much of north-western Europe from the 4th century CE onwards. Beginning with basic animal shapes, through the Migration & Vendel periods (c. 375-800 CE) when – surprisingly – mass migrations took place throughout Europe, Scandinavia gradually embraced full-blown animal ornamentation, being influenced by Scythic, Oriental, Celtic and Roman art along the way.

In the early 20th century CE, Swedish archaeologist Bernhard Salin divided pre-Viking Age Germanic ornamentation into three styles: styles I, II and III. Style I, which flourished in the 6th century CE in north-western Europe, saw metal chip-carving embellish objects with separate animal-body parts mostly along the borders of central, abstract patterns. Style II was popular throughout Germanic cultures during the 7th century CE and focused on non-naturalistic animals (including otherwise rare predatory animals) forming interlacing patterns, and on the aristocratic image of a horse and rider. By contrast, from the 7th century CE into the early Viking Age, Style III developed within Scandinavia itself. Its basic motif often had two band-shaped animals seen in profile, with openwork shoulders and hips and tendril-outgrowths, the bodies arranged in the form of a lyre. Although this style changed over course of the next few centuries, the motif of the stylised animal in profile remained a central motif in Scandinavian art until the Middle Ages (and even beyond, staying alive in folk art genres although otherwise abandoned).

Style E (Oseberg & Broa)

Style E – the first of the properly Viking Age animal ornamentation styles when it comes to dates – is generally seen as a sub-category or offshoot of Style III and was in vogue from the second half of the 8th century CE through to nearly the end of the 9th century CE. Although related to the broader Germanic tradition, this style is very much native Scandinavian. Animals, often set within a framework, became more abstract than before, displaying long, almost ribbon-shaped, curving bodies with intertwining limbs that develop into open loops and tendrils. Their heads are small and are shown in profile but have big, bulging eyes. Specific variants include a double-contoured creature with a nearly triangular body, a beaked head and forked feet; a round-headed, more coherent animal with little claws and a flap; and the standout so-called gripping-beast style. Anne-Sofie Gräslund vividly describes the gripping-beast:

Its thin ribbonlike body is set off by large muscular shoulders and hips, and its legs end in paws, which grip tight to everything—to the edge of the ornamentation border, to neighbouring animals, or to its own body. The tigerlike beast appears filled with energy and seems to cling to the assemblage at all costs. (Fitzhugh & Ward, 63-64).

Famous for high-quality finds from both the Oseberg ship burial and graves found at Broa on Gotland, Style E is sometimes referred to as the 'Oseberg Style' or the 'Broa Style'. At Broa, 22 gilt-bronze bridle-mounts were found in a grave, indicating the clearly wealthy owner's horse would have been well-kitted out indeed. The decorations show animals with eyes so large not much space remains for the rest of their heads. Of course, these are standout items; more basic items such as the oval brooches used to fasten women's clothing were widely decorated in this style, too, demonstrating it permeated Scandinavian society at large.

The Borre Style

Around the mid-9th century CE, the Borre style made its grand entrance, succeeding Style E and remaining popular until at the latest the late 10th century CE. Fully on board with the previously introduced gripping-beasts, the Borre style's main motif put the beast wholly in the limelight: a single, contorted gripping-beast, its body forming a sort of curved ribbon between its two hips, its face triangular – catlike or masked – with its claws gripping either the border or part of its own body, dominates the scene. A second variant depicts a semi-naturalistic animal seen from the side. The Borre style's real giveaway is the introduction of the ribbon plait, known as the 'ring-chain'. Imagine two interlaced ribbons, their intersections overlaid with interlacing circles covered with lozenges (diamond shapes) or other geometrical figures. Crossways nicks could be added for extra bling, and filigree and granulation were frequently-used techniques.

The Borre style is named after the location of a ship burial in Borre, Vestfold, Norway, where gilt-bronze harness mounts displaying this style were found. It was hugely popular not just across Scandinavia but throughout the Viking colonies, too. With the Viking expansion at its maximum at this point in time, this means the Borre style appeared – in more or less pure forms - from the British Isles, including Wales and Scotland, to Russia and eastern Europe, and even to Byzantium. As David Wilson concludes, 'no other style was so widespread' (Brink & Price, 328). With Scandinavia gradually converting to Christianity in the last stages of the 10th century CE, the Borre style spans the last full period of paganism and its accompanying burial customs, perhaps explaining the large volume of Borre objects that are preserved.

The Jelling Style

Probably first cropping up just before 900 CE, the Jelling (or Jellinge) style flourished during the mid-10th century and then gradually developed into the succeeding Mammen style. Artistically close friends with – and largely contemporary with – the Borre style, the Jelling style is less common and seems to take inspiration from Style III from the pre-Viking Vendel period (c. 550-c. 800 CE) and Style E with its ribbon-shaped animals seen in profile. Its main motif is an s-shaped beast with a beaded or patterned body, which is usually double-contoured, its head appearing in profile and sporting a round eye and tendrils sprouting out from its nose and neck. Intertwining ribbon interlace and foliage often accompany the animals. The Jelling style is rarely directly merged with the Borre style, but objects sometimes feature both styles used side by side.

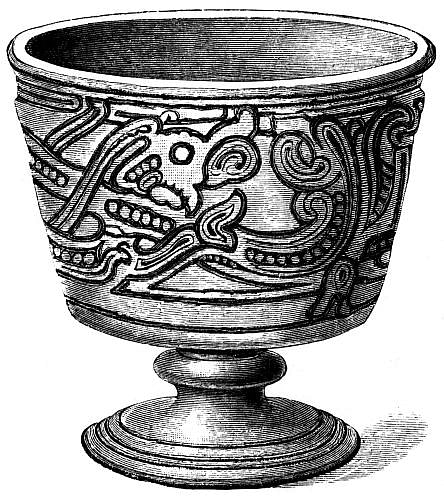

The Jelling style was named after a small silver cup decorated in this style, found in a royal burial place at Jelling, Denmark, and just like the Borre style, it was popular not just inside Scandinavia but also in Russia and the British Isles. The north of England even became home to a melting-pot Anglo-Scandinavian style which contained both clear Borre and Jelling elements.

The Mammen Style

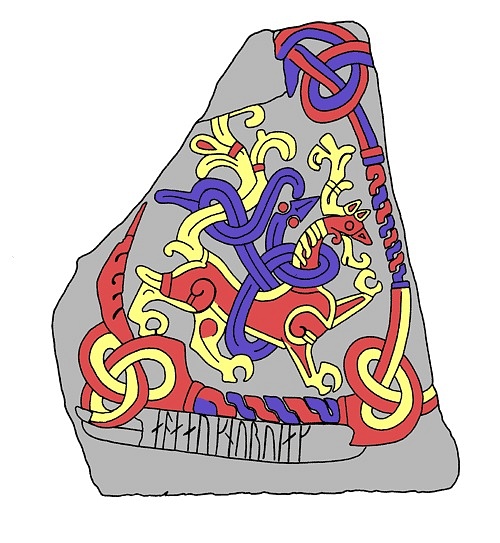

The Mammen style developed from the Jelling style from c. 950 CE onwards, prevailing for a few decades while gradually merging with the succeeding Ringerike style, its best-before date expired around 1000 CE. Its main motif really stands out: a great four-legged beast – a griffin or a lion – with a double-contoured body and spiral-shaped hips and shoulders, battles with a snake. The Mammen motif is bold and dynamic, laid out in an asymmetrical way, unaligned with the surface's axis, and embellished with branching plant ornamentation such as acanthus-shaped crests. The acanthus-shapes betray a likely English influence; they greatly resemble the Anglo-Saxon Winchester style and probably crossed over to Danish carvers during the first half of the 10th century CE, when the Danish presence in England was at its height. The lion or griffin, which is not originally a Scandinavian motif either but suggests a Christian influence, might also have reached Scandinavian ears through this route, although this story is harder to trace.

The style's most famous example is a runestone found at Jelling in Denmark and imaginatively known as the Jelling Stone which depicts the iconic twisting great beast entwined with a snake. Otherwise, although not many Mammen objects are preserved, the style is found throughout Europe from Ukraine through to Spain, the British Isles, and obviously within Scandinavia itself.

The Ringerike Style

The Ringerike style developed from the Mammen style by around 990 CE and remained popular until c. 1050 CE. Named after memorial stones from Ringerike, north of Oslo, Norway, this style strongly resembles its predecessor, especially where it concerns the large animal motifs – curving snakes, lions, or ribbon animals which strike dynamic poses. However, where Mammen is more wavy and chaotic in its embellishment, the Ringerike designs are laid out on an axis and show a more disciplined, basic asymmetry, with taut and evenly curved scrolls of plant motifs, tendrils and loops. These become even more important in the overall design and create a rich impression of elegant movement, even though the animals are beginning to be a cause for worry when looking at the amount of these tendrils and plants that sprout out of their bodies. Luckily, some tendrils also grow by themselves.

The Ringerike style dominates the runestones of south- and middle Sweden as well as on Gotland, while also appearing in Denmark and in modified form in Norway. In metalwork, the style did not lag behind, either, and some splendid examples are preserved, such as two copper-gilt weather vanes found in Sweden (one from Källunge, Gotland, and one from Söderala, Hälsingland). Loops flow from an axis, taking the form of snakes from which symmetrically-placed tendrils sprout. Their heads both have a pear-shaped eye whose tip points towards the snout – a characteristic feature of the Ringerike style. Acanthus-bud motifs – another staple within this style, and quite probably an English influence – fill up two corners. Presumed to have been brought along to England by Cnut the Great (r. 1016-1035 CE), King of Denmark, England and Norway, the Ringerike style was both popular and influential across the British Isles. It was especially enthusiastically adopted in Ireland, where it struck such a chord it developed independently, even appearing on objects originating from native Irish contexts such as the Clonmacnois crozier.

The Urnes Style

The last of the Scandinavian animal ornamentation-based art styles is the Urnes style, which was most prominent between c. 1040 CE and c. 1100 CE. Because of its prevalence on the runestones of Uppland, Sweden, the term 'runestone style' is also found there. Sophisticated, elegant and sleek, even decadent, the Urnes designs are often asymmetric and form an interweaving mass of sinuous, gently curving animals and snakes. There are no abrupt transitions or breaks in the lines. Its characteristic motif is that of a great four-legged beast often struggling with surrounding snakes, biting each other. The greyhound- or deer-esque animals have long necks and slim heads, with snake-like creatures (sometimes with one foreleg, sometimes just a tendril ending in a snake's head) coiling around the design in figure-eight loops. The pointed, almond-shaped eyes fill almost the entire heads, which are usually depicted in profile. Variation existed, too, which is most obviously visible in metalwork of the time.

The style was named after the stave church that stands in Urnes, Sogn, western Norway, which was rebuilt in the 12th century CE and recycled decorated wood of an earlier date which depicts this particular style. The Urnes style is often found in a Christian context, highlighting the idea that Viking Age art styles were not specifically 'pagan' per se but part of society at large. Outside of Scandinavia, it is sometimes found in England and, like the Ringerike style, it was especially well-liked in Ireland. Here, the Urnes style flourished from c. 1090 CE onwards to the end of the 12th century CE and even beyond, impacting not just metalwork but also stonework and manuscript decoration.

The End of the Viking Age

Although the use of animal ornamentation petered out around 1100 CE, it did not disappear abruptly and was actually used on some early 12th-century CE ecclesiastical objects (Scandinavia had been Christian since c. 1000 CE). The Lisbjerg altar from Jutland, Denmark, for instance, combines the native Viking style with European Romanesque. Furthermore, animal art remained in use in peasant society for many centuries after the end of the Viking Age – surely a testament to its role and appeal in this culture.