The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) was the last major European conflict informed by religious divisions and one of the most devastating in European history resulting in a death toll of approximately 8 million. Beginning as a local conflict in Bohemia, it eventually involved all of Europe, influencing the development of the modern era.

The war is most easily understood by dividing it into four phases:

- Bohemian Revolt (1618-1620)

- Denmark’s Engagement (1625-1629)

- Sweden’s Engagement (1630-1634)

- France’s Engagement (1635-1648)

The Protestant Reformation had encouraged religious dissention and social unrest since 1517 which was addressed by the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, establishing the policy of cuius regio, eius religio (“whose realm, their religion”) by which a ruler chose whether their territory would be Catholic or Lutheran (then the only recognized Protestant sect). When the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II (l. 1578-1637) became king of Bohemia in 1617, it upset his largely Protestant subjects, initiating the Bohemian Revolt - and the Thirty Years’ War – in May 1618 after the Second Defenestration of Prague and the Protestants support for their choice of monarch, Frederick V of the Palatinate (l. 1596-1632).

Frederick V’s forces were defeated in 1620 at the Battle of White Mountain and Protestant Denmark engaged in the conflict in 1625, an event usually referenced as the first intervention of a foreign power in the war though, actually, the Dutch Protestants had been supplying Frederick V’s forces with arms and other resources since 1618 and Catholic Spain had supported Ferdinand II. The Protestant Christian IV of Denmark (r. 1588-1648) entered the war for religious reasons and to protect his commercial interests but also because King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (r. 1611-1632) was poised to enter the war as a Protestant champion, an honor Christian IV wanted for himself.

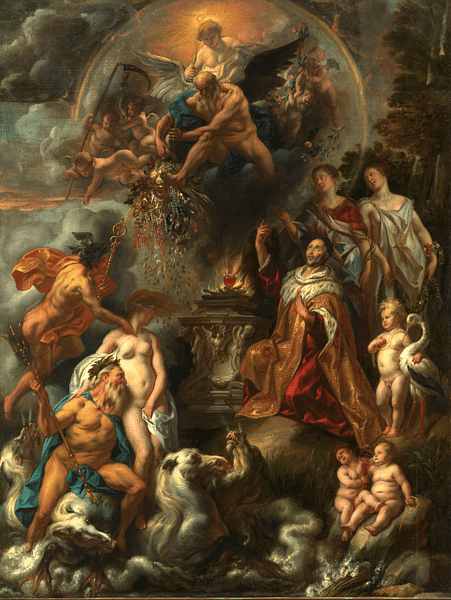

Christian IV was no match for the Imperial forces under Catholic mercenary leader Albrecht von Wallenstein (l. 1583-1634), however, and agreed to a peace and withdrawal of Denmark’s troops and Scottish mercenaries in 1629. Adolphus had supported Christian IV since 1628 but in 1630, with resources from the Catholic Cardinal Richelieu of France (l. 1585-1642) took the field against Wallenstein. Richelieu supported the Protestant king against Catholic Imperial forces in the interests of maintaining a balance of power between France and neighboring regions controlled by the powerful Habsburg Dynasty. After Adolphus was killed in battle in 1632, the Swedes continued the fight, supported by the French in the final, and bloodiest, phase of the war.

There was no winner as the war was concluded in 1648 by the Peace of Westphalia (which also ended the Eighty Years’ War between Spain and the Netherlands) a document essentially just restating the same terms as the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 regarding religion. Results of the war include:

- Sovereignty of States

- Recognition of Calvinism

- Dutch Independence

- Innovations in warfare

- Swiss Independence

- France as a major power

- Decline of the Spanish Empire

- Portuguese Independence

- Weakening of the Holy Roman Empire

The Thirty Years’ War is recognized as the “official” end of the Protestant Reformation as, by the time it concluded, Calvinism was accepted along with Lutheranism and Catholicism as a legitimate belief system and so the period of the development of Protestant sects is thought to have concluded by 1648 – though this did nothing to resolve religious conflict going forward and, according to some scholars, the reformation is ongoing today. The war is also understood as the beginning of modern warfare as practiced by Adolphus Gustavus and the establishment of the modern international system of statehood, marking the conflict as a watershed event in the transition to the modern era.

Causes & Background

The Thirty Years’ War was caused by several factors including:

- Perceived imbalance of power in the region

- Resentment of the Habsburg Dynasty and their control of commerce

- Weakening of the power of the Holy Roman Emperor

- Commercial Interests in the Region

- Religious dissention

Religious differences, and the inability to resolve them peacefully, however, were the immediate cause and were informed by the three major European religious reformations:

- The Bohemian Reformation (c. 1380-c. 1436)

- The Protestant Reformation (1517-1648)

- The Counter-Reformation (1545-c.1700)

The Bohemian Reformation was begun by Catholic priests and theologians seeking to return the Church to the simplicity of its early years and its greatest advocate was Jan Hus (l. 1369-1415) whose execution as a heretic ignited the Hussite Wars (1419-1434). At the Council of Basel in 1436, Bohemia was granted freedom of religion and the Bohemian Church was allowed to conduct services in accordance with its own beliefs.

In 1517, the Catholic monk and theologian Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) posted his 95 Theses in Wittenberg, beginning the Protestant Reformation which was furthered by Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) in Switzerland and then by John Calvin (l. 1509-1564). The Catholic Church met the challenge of these reformers with the Counter-Reformation beginning in 1545, denouncing Protestant teachings as heresy and reasserting the Church’s position as sole spiritual authority. Long before 1545, people began to identify strongly as either Catholic or Protestant and, within the Protestant sects, as adhering to one leader or another, creating further dissention.

Civil conflict informed by religious division erupted in 1524 with the German Peasants’ Revolt and continued with the Knights’ Revolt and Schmalkaldic War until the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 was called to resolve the dispute. Among the provisions was that the ruler of the region chose the religion of their kingdom. This concept worked in principle but was problematic if the monarch’s religion differed from that of the majority of his subjects.

The Bohemians had been used to practicing their faith in their own way since 1436 and those who no longer wished to conform to the orthodox Bohemian Church aligned with Luther (whose teachings resonated with those of Hus) and were granted their freedom of religion. When the zealously Catholic Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, became King of Bohemia, even though he promised religious tolerance, he was distrusted because of his past actions persecuting Protestants elsewhere. Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria (l. 1573-1651), also a devout Catholic, supported Ferdinand II by refusing the crown of Bohemia and supplying armed forces in defense of Ferdinand II’s claim to the throne.

Bohemian Revolt

The Bohemian Revolt began when Protestant nobles, led by Count Thurn (l. 1567-1640), objected to legal decisions favoring Catholics and met with three of Ferdinand II’s representatives at Prague Castle to discuss the situation. Unhappy with the proceedings, Thurn and his colleagues threw the representatives out the window in what has come to be known as the Second Defenestration of Prague (the First Defenestration being the event that began the Hussite Wars).

All three men lived but the incident was seized upon by both factions as propaganda with the Catholics claiming they had been caught and carried safely to the ground by angels and the Protestants countering that they only survived by landing in a large pile of manure. Thurn took power and encouraged Protestant princes in Austria and Silesia to do the same while Frederick V hired the mercenary general Ernst von Mansfeld (d. 1626) to lead the armies in support of Thurn. Mansfeld was defeated in 1619 but by then the Protestants had withdrawn all support from Ferdinand II and offered the crown to Frederick V, who accepted.

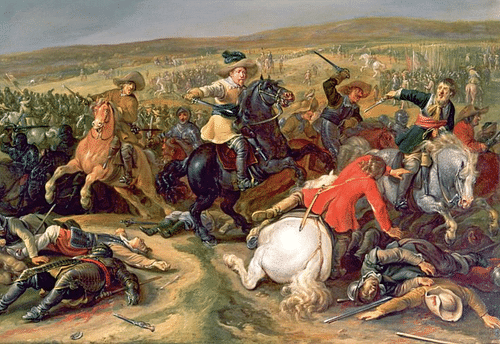

The Catholic faction declared this act illegal as Ferdinand II was the rightful king (as well as Holy Roman Emperor) and hostilities continued until November 1620 when the Catholic Imperial troops under Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly (l. 1559-1632), supplied by Maximilian I, defeated the Bohemians under Thurn and Christian of Anhalt (l. 1568-1630) at the Battle of White Mountain. Support for Frederick V was broken, and the Imperial armies took Prague, ending the revolt. Frederick V would later die of fever from an infection in 1632.

The Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648, also known as the Dutch Revolt) between Spain and the Netherlands was then in the period known as the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621), allowing Catholic Spain and the Protestants of the Netherlands to send resources to Bohemia to help their respective causes. The Bohemian Revolt then became an international conflict and tensions escalated in 1623 when Ferdinand II took the lands and titles from Frederick V, ignoring Protestant princes who were now convinced Ferdinand II would impose Catholicism on the region. Ferdinand II had the support of the Catholic Habsburgs who, at this time, controlled Spain, the Netherlands, Naples, Milan, and most of the Holy Roman Empire.

Denmark’s Engagement

Christian IV of Denmark relied on steady trade through the northern regions of the Holy Roman Empire and the Baltic which was now threatened and, concerned that Ferdinand II’s act against Frederick V signaled a Catholic push north toward Denmark, approached his fellow Protestant nobles in Hamburg and Bremen, offering his assistance. He joined with Mansfeld in an effort to defeat Ferdinand II’s champion Wallenstein with support from England, the Netherlands and, on a smaller scale, France which was dealing with its own problems at the time.

Throughout the war thus far, both sides had difficulties supplying their troops and so the armies took to living off the land, destroying farms and killing civilians as they marched. It did not matter which cause a village supported as Protestants and Catholics suffered equally at the hands of Wallenstein’s Imperial army or Mansfeld’s rebels. Wallenstein himself was handsomely rewarded by Ferdinand II but the riches never trickled down to the troops. Christian IV, hearing of the deaths of Protestant non-combatants, entered the war as their champion but Protestant rebel forces by this time had probably raped and killed as many Protestant civilians as Wallenstein’s Imperial Catholic troops.

Christian IV’s main motivation was protecting his commercial interests in the region and claiming the title of Christian Champion before it could be taken by Gustavus Adolphus. He met the Count of Tilly at the Battle of Lutter in 1626 and was defeated. Afterwards, the troops and resources he was counting on from England and the Netherlands failed to materialize and Mansfeld died in 1626 of natural causes. Christian IV, without resources or his experienced general, was outmaneuvered by Wallenstein in 1627 and, in 1628, appealed to Adolphus for help, which was sent. By 1629, however, Christian IV sued for peace and signed the Treaty of Lubeck which guaranteed the safety of his interests in return for his promise to stay out of the war.

Sweden’s Engagement

Gustavus Adolphus arrived in the region in 1630 at the head of approximately 20,000 troops, far fewer than those commanded by Tilly or Wallenstein, but his military innovations more than made up for a lack of manpower. Adolphus seems to have been aware of the advances in warfare initiated by the great Czech general Jan Zizka (l.c. 1360-1424) in the Hussite Wars, including his wagon fort which could serve in both offense and defense. This versatility had given Zizka’s troops the decisive advantage of mobile artillery, the innovation Adolphus is most famous for. Adolphus had also taken note of the novel tactics of Maurice of Orange (also known as Maurice of Nassau, l. 1567-1625, son of the general and statesman William the Silent, l. 1533-1584), notably controlled volley fire and the countermarch which allowed for continuous fire and reformation while reloading.

Drawing on both these resources, Adolphus created a cross-trained army in which every soldier could perform the duties of any other: infantry could also be cavalry, cavalry artillery, artillery infantry and each contingent was treated with the same respect as any other. He also introduced mobile artillery which worked like Zizka’s wagon forts, turning offensive positions into defense, or vice versa, and moving precisely where he needed them to be in quick formations. In addition to his stationary artillery, these guns proved quite effective.

He forbid any plunder or scavenging by his troops and made sure they were well-paid and fed thanks to resources from France, the Dutch, and his native Sweden. After consolidating his forces, he defeated Tilly at the First Battle of Breitenfeld in 1631 and was again victorious at the Battle of the River Lech (Battle of Rain) in April 1632 during which Tilly was wounded and later died. In September 1632 he was outmaneuvered and outfought by Wallenstein at the Battle of the Alte Veste but kept his troops intact. The two generals met again at the Battle of Lutzen in November 1632 where Adolphus was killed but the Swedish army won the day when command was assumed by Bernard of Saxe-Weimar (l. 1604-1639) who rallied the troops.

Bernard then left the Swedish forces and Adolphus’ right-hand man Axel Oxenstierna (l. 1583-1654) took control of the Swedish forces, winning another victory in 1633. Wallenstein, whose retreat from the field at Lutzen had given the Swedes that victory, was removed from command by Ferdinand II and assassinated by his senior staff in 1634. He was replaced by Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria (l. 1609-1641), Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, who defeated the Swedish-German coalition decisively at the Battle of Nordlingen in September 1634, effectively neutralizing the Swedes for the moment and causing their German allies to defect to the Imperial cause.

France’s Engagement

Ferdinand II now appealed directly to Spain for resources to continue the war to its conclusion, forcing Cardinal Richelieu to have France declare war on Spain and commit more resources to the conflict, commissioning Bernard of Saxe-Weimar to lead mercenary forces. This last phase of the war, still fought primarily in the Holy Roman Empire (which included Bohemia), involved France, Spain, the Netherlands, England, Portugal, Sweden, Denmark, and Poland-Lithuania.

After years of conflict, farmlands had been decimated and food was scarce, causing famine, and many – combatants and non-combatants – died of starvation. Troops again were forced to live off the land but there was little land to live off and still no compromise could be reached, and hostilities raged on. Disease ravaged the land and many civilians turned on each other, robbing and killing neighbors for something to sell so they could eat. The animal population, including cats and dogs, declined as rapidly as the human while the war continued with no end in sight.

The Swedes steadily lost all the gains they had made until 1636 when they won the Battle of Wittstock while France landed forces in the region to support them. In 1637, Ferdinand II died and was succeeded by his son Ferdinand III (l. 1608-1657) who seemed to have no more idea of how to end the conflict than his father had. French forces continued to support Swedish engagements as well as seize their own victories, but the Imperial armies still held their ground and made their own advances.

In 1641, Lennart Torstensson (l. 1603-1651) succeeded Johan Baner (l. 1596-1641) as Swedish Field Marshal. Both had served under Gustavus Adolphus and Baner had tried to continue his policies of forbidding troops to scavenge or molest the citizenry but, even with French support, lacked resources and the Swedish forces prior to Torstensson reverted back to pillaging citizens. Torstensson was able to resupply the troops following Baner’s death and led his troops to victory through 1645. The French-Swedish alliance continued to press their advantage through 1646 but could not manage a decisive victory that would end the war. While refusing to admit his situation was increasingly hopeless, Ferdinand III finally agreed to negotiations in 1648 and the Peace of Westphalia ended the war.

Conclusion

As noted, the conflict was primarily fought in the region of the Holy Roman Empire which, though it included parts of modern-day Italy, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, and others, was primarily the area of modern-day Germany. The war almost completely destroyed many of the villages throughout the region and devastated the city of Magdeburg which lost 20,000 of its 25,000 inhabitants and 1,700 of its 1,900 buildings and homes. The sacking of villages drove refugees into cities already overpopulated and rife with disease, increasing the death toll.

Foreign soldiers were blamed for bringing the plague and other illnesses, encouraging a national resentment against other nations which would later be exploited by leaders of Prussia, Brandenburg, and then Germany through reminders of atrocities inflicted on the Germanic population by “the other” in mobilizing for later conflicts. The German memory of the Thirty Years’ War, handed down generation-to-generation and popularized by German writers and poets, would go on to inform propaganda for both World War I and World War II.

Even so, the Peace of Westphalia, reasserting the religious sovereignty of the Peace of Augsburg, established the concept of national sovereignty which prohibited any nation from interfering in the laws governing another, eventually giving rise to the modern international system of governments. Once Calvinism was recognized, freedom of religion – at least on paper – became more widespread and there was an increase in literacy as schools were established, by both Protestants and Catholics, to enable a better understanding of scripture.

In spite of these advances, and others, it should be noted the war killed approximately eight million people. At the Battle of Nordlingen in 1634 alone, approximately 16,000 combatants died in a single day and that is not counting non-combatants in the area. It is a certainty that many of those, directly or indirectly involved in the war, could not have cared less about the claims of Ferdinand II or Frederick V but it does seem that many, if not most, were heavily invested in their religious identification which attached them to one side or the other.

After the destruction of the Germanic territories of the Holy Roman Empire between 1618-1648 and the deaths of millions, the religious aspect of the conflict reflected exactly what had already been resolved in 1555 at Augsburg. The conflict was not resolved in any new way; everyone was simply tired of fighting. Still, it was not long before both Catholics and Protestants found their second wind and religious differences would continue to inform civil unrest going forward and continue to right up to the present day.