This text is part of an article series on the Delian League.

The third phase of the Delian League begins with the Thirty Years Peace between Athens and Sparta and ends with the start of the Ten Years War (445/4 – 431/0 BCE). The First Peloponnesian War, which effectively ended after the Battle of Coronea, and the Second Sacred War forced both the Spartans and Athenians to realize a new dualism existed in Hellenic affairs; the Hellenes now had one hegemon on the mainland under Sparta and one in the Aegean under Athens.

By the early 450's BCE, the Delian League had secured for Athens an almost inexhaustible grain supply, enormous wealth, unprecedented control of the Aegean as well as dominance in central Greece, and thus the Athenians possessed almost absolute security from invasion. By 445/4 BCE, however, the Delian League suffered a devastating defeat in Egypt, the loss of Megara to the Peloponnesian League, and several Boeotian poleis had successfully rebelled.

The Delian League agreed to surrender Nisaea, Pagae, Troezen, and Achaea (but retained Naupactus), and both sides drew up a final list of allies (who could not then change allegiances). The remaining independent poleis, which included Argos, could then ally with whomever they wished. Scholars debate whether or not the treaty also stipulated free trade amongst the Greeks. Athens now retarded any grand expansionist schemes it may have had for the Delian League and focused instead on securing it within terms of this Peace.

REORGANIZATION OF THE DELIAN LEAGUE

The Athenians spent the next few years reorganizing and consolidating control of the Delian League. They made an extraordinary assessment in 443/2 BCE and divided the poleis into five administrative districts: Ionia, Hellespont, Thrace (or Chalcidice), Caria, and the Islands. Athens also continued to establish important colonies (e.g., Colophon, Erythae, Hestiaia, and, most notably, the Panhellenic Thurii in Italy).

By 440 BCE, membership increased (or was restored) to 172 poleis. The growing number of Athenian garrisons and cleruchies throughout the Aegean, alongside the diminished role of League synods, further drove Athens to institute varying changes in relation to its allies of the League. The original founders of the Delian League did not contemplate the possibility their chosen hegemon would ever interfere in local judicial proceedings of the member poleis. They all took their individual autonomies for granted.

Nevertheless, when the Athenians passed decrees, which necessarily affected allied poleis, they made provisions for settling offenses by Athenian jurists in Athenian law-courts. Athens also instructed allies to permit various appeals to those same courts and to impose penalties as Athenians imposed such penalties. Moreover, as stated, Athenian citizens abroad remained protected by Athenian laws.

The Athenians seemed intent on settling disputes within the League quickly and fairly by relying on the "rule of law" rather than naked force. The effect of these alterations, however, appeared far different to members of the League. The changes meant the removal of important litigation from local courts and magistrates, it diminished their independent authority, and it had Athens settle these matters ([Xen.] Ath. Pol. 1.16-18). Several allies thought they had now become subject to the tyranny of Athenian jurists.

THE SAMIAN WAR

War erupted between Samos and Miletus over the polis Priene (440 BCE) – the Samian War – and the clash presented a unique problem for the Delian League. Samos had remained independent, paid no tribute, and stood as one of the very few poleis which still had a formidable navy. Miletus, on the other hand, had revolted not once but twice from the League, and the Athenians had subsequently deprived it of a navy.

The Athenians understood they might act wrongly if they acquired Samos but decided it far more dangerous to let the polis remain free. Athens reacted swiftly and decisively. They dispatched 40 triremes, seized 100 Samian hostages, and promptly replaced the polis' oligarchy with a democracy. Athens fined Samos 8 talents, installed a garrison, but then the Athenians departed as quickly as they had arrived. The League's action, however, did not cow the Samians; it infuriated them.

The Samian oligarchic leaders immediately requested assistance from Lydia, and, with the help of Persian mercenaries, overran the Athenian garrison, and declared themselves "enemies of the Athenians." The Samians also made an appeal to Sparta. They now intended to contest "supremacy of the sea" and seize it from Athens (Thuc. 8.76.4; Plur. Vit. Per. 25.3, 28.3).

The near simultaneous rebellions of Byzantium as well as numerous poleis in the Carian, Thraceward, and Chalcidice Districts revealed the seriousness of the unrest – even Mytilene intended to join the revolts and awaited word from Sparta. Some of these poleis received support from Macedon. Sparta summoned the Peloponnesian League and a divisive debate ensued. The Corinthians argued strongly against intervention, advocating that each alliance should remain "free to punish its own allies" (Thuc. 1.40.4-6, 41.1-3). The Spartans remained silent.

The Athenian response again proved decisive and swift. With reinforcements from Lesbos and Chios, the Athenians besieged Samos. After nine months, they crushed the revolt. Samos would pull down its walls and pay reparations of 1,300 talents (in 26 installments). On the other hand, Samians did not surrender their navy or pay tribute, nor did the Athenians compel the island to accept a colony or cleruchies. Byzantium, who had, in any case, showed only moderate resistance, surrendered shortly thereafter, and the Athenians permitted them to rejoin the League with minimal punishment.

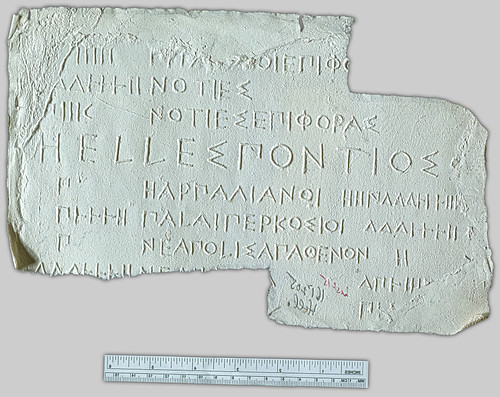

EPIPHORA & LOSS OF THE CARIA DISTRICT

The Tribute Lists for 440/39 BCE show another change in procedure. For the first time, the treasury purposely lists some poleis twice: first with their normal assessments and then a second entry with an ἐπιφορά or epiphora (lit. a 'bringing upon' or 'repetition'): a small additional charge the nature of which is not yet clear.

The term had many uses, but for the League, it appears the Hellentamiai imposed penalties or recorded additional deposits. The treasurers, for instance, seem to have charged interest due on late payments (3 minai per talent per month) or imposed a simple fine. The entry may also indicate, however, a voluntary additional payment for some specific service rendered. Most of these second payments occurred in the Ionia and Hellespont Districts.

The suppression of Samos did not prove a total success; by 438 BCE, about 40 of the more remote and inland poleis from the Caria District permanently disappear from the Tribute Lists. Caria had always proven difficult to control and tribute rolls often fluctuated. The combined assessment amounted to not more than 15 talents. Any force sent to collect arrears would have cost more than the lost tribute. Like Cyprus, Caria possessed little strategic value. The Athenians subsequently merged the remaining poleis into the Ionia District.

Even though the League relaxed its hold on its southeast periphery, the unrest at Byzantium exposed deeper problems in the Hellespont region. The Mediterranean possessed four great granaries, and the littoral of the Euxine Sea (i.e., imports from the Ukraine region) had become the most critical to Athens and its large population. Unfettered shipping remained paramount.

PERICLES & THE BLACK SEA

The following summer, to counter the unrest, Pericles, son of Xanthippus, launched his now famous Expedition to the Black Sea (437 BCE). The Athenian goal was simple: impress upon the more remote League members, as well as nearby barbarians, the value and importance of Athenian friendship. Athens put to sea an audaciously large and well-equipped fleet. Pericles "displayed the greatness of Athenian power, their confidence and boldness in sailing where they wished, having made themselves complete masters of the sea" (Plut. Vit. Per. 20.1-2).

During this time, Athens also established sizeable colonies at Amisus, Nymphaeum, Brea, and finally, and most importantly, Amphipolis (on the Strymon river near Macedon). Amphipolis would serve as an impregnable fortress to prevent rebellion and guard the Hellespont while also securing timber and precious metals from the area.

THE EPIDAMNIAN INCIDENT (CORCYRAN CONFLICT)

A relatively minor event, which began in Epidamnus, would soon engulf Corcyra and Corinth (and several of its colonies) and eventually lead the two hegemons Sparta and Athens into open conflict and ultimately result in the great Peloponnesian War (435 - 432 BCE).

Epidamnus, a colony of Corcyra (itself a colony of Corinth), became embroiled in a civil war, which involved some local barbarians. They asked their mother polis to assist. Epidamnus rested on the eastern coast of the Adriatic, more than a hundred miles to the north of Corcyra and thus existed far beyond either the Peloponnesian or Delian Leagues' interests. Corcyra refused to assist. Epidamnus, after consulting Delphi, subsequently appealed to the Corinthians. They responded vigorously with assistance from Ambracia and Leucas (Thuc. 1.26.2-3), but Corcyra, who had a long-standing quarrel with Corinth, would not tolerate such interference. The Corcyrans moved to intervene but soon realized that they had underestimated Corinthian resolve.

Corinth received additional assistance from Megara, Cephallenia, Epidaurus, Hermione, Troezen, Thebes, Phlius, and Elis. Many of these poleis were also members of the Peloponnesian League, and thus this Epidamnian Incident had captured the attention of Sparta. Corcyrans historically avoided alliances and saw Corinth commanded considerably more resources. To avoid war or the loss of Epidamnus, they asked for arbitration from the Peloponnese or Delphi, or failing that, threatened to seek assistance elsewhere. The Corinthians ignored the veiled threat and refused, but they too underestimated Corcyra's own resolve.

A modest Corinthian force of 75 ships sailed to Actium but confronted 80 defending vessels. Corcyra proved victorious, destroying 15 Corinthian triremes. The defeat only hardened Corinthian determination, however, who set about immediately to construct a larger fleet. Corcyra had no choice and sought assistance from mighty Athens.

THE BATTLE OF SYBOTA

The Athenians agreed to an ἐπιμαχία (defensive alliance) and dispatched ten triremes in support of Corcyra. This time, Corinth approached Corcyra leading 155 ships. They brought contingents from their colonies Leacus, Ambracia, and Anactorium, as well as their allies Megara and Elis. On the other hand, Epidaurus, Hermione, Troezen, Cephallenia, Thebes, and Phlius saw the conflict now involved the Athenians and elected to remain neutral. The Corcyrans possessed 110 ships to defend (plus ten Athenian vessels acting as a type of reserve).

The Corinthians gathered at Cheimerium, while the Corcyrans established a base on the island of Sybota. The resulting battle proved clumsy, but the Corinthians eventually routed the Corcyran fleet when 20 additional Athenian triremes suddenly appeared on the horizon. The Corinthians, fearing an even larger Delian League force would arrive, withdrew and viewed the interference as an open breach of their own treaty with Athens. The Athenians retorted that they had only supported their new ally and wished no war with Corinth (433 BCE).

Both sides declared victory, but the Corinthians then proceeded to seize Anactorium. Their quarrel with Corcyra had not ended, and they now had cause and made preparations for war against the Athenians. At the same time, representatives from Leontini and Rhegion arrived in Athens from Italy, and the Athenians accepted them into the alliance. The Ionian poleis of Sicily became fearful that Dorian Syracuse (also originally a colony of Corinth) might use Athenian preoccupation in any upcoming war to swallow them and thus joined the Delian League.

THE FINANCIAL DECREE OF CALLIAS

The Assessment of 434/3 BCE displays two new conditions: poleis that initiated tribute themselves, and poleis that accepted assessment by special arrangement. The volatile and constantly changing conditions in Thrace and Macedon make definitive conclusions difficult, but, in general, it seems some poleis in the region recognized the benefits of Athenian protection and voluntarily requested to pay a tribute to the Delian League.

The Athenians also passed two decrees on the proposals of Callias, son of Calliades. The measures concentrated various treasuries in the Opisthodomos. Once the League paid its debts, the treasurers would use surpluses on the dockyards and walls, but all sums exceeding 10,000 drachma needed a special vote of the Ekklesia. The Financial Decrees of Callias have provoked continuous controversy amongst scholars, but they appear to show Athenians had grown convinced another major war had become unavoidable and imminent. Whether or not such a conflict would stay focused against Corinth or come to involve Sparta, the Athenians readied the resources of the entire League for that war.

THE REVOLT OF POTEIDAIA & THE MEGARA DECREE

While assisting Corcyra at Sybota, the Athenians also decided to become involved in Macedon, ostensibly to protect League interests in the area, but more likely to remove the fickle and untrustworthy King Perdiccas II and thus the constant threat of unrest from Thracian tribes in the region. Assessments in this area of the League (Pallene and Bottice) had risen since 438/7 BCE (presumably because of Thracian and Macedonian encroachments). Perdiccas then sent embassies to Sparta.

Perdiccas had long demonstrated a willingness to side against Athens when an opportunity presented itself. Athens dispatched 30 triremes with 1,000 hoplites to support both Perdiccas' brother and nephew in a civil war that had developed there. About the same time, the Athenians issued what has become known as the Megara Decree (more than one decree actually existed, and the precise dates of their passages remain unknown). Athens essentially forbade the Megarans access to the Athenian agora and all harbors under Athenian rule.

The Decrees' exact meanings remain debated, but, by suddenly closing the harbors of the entire Delian League, Athens demonstrated its power to disrupt the flow of trade when provoked. The Athenian Ekklesia further issued an ultimatum to Poteidaia, a tribute paying Delian League member in the Chalcidice District since 445/4 BCE but also a Corinthian colony: the Poteidaians must dismiss their Corinthian magistrates. The Poteidaians flatly refused and appealed to Sparta for assistance (433/2 BCE). The Ephors promptly promised to invade Attica.

Poteidaia's overt resistance resulted in several rebellions in the Chalcidice area. Corinth, moreover, dispatched a force of 2,000 volunteers to aid their colony. The Corinthian action compelled Athens to dispatch an additional 40 triremes and 2,000 hoplites to suppress the now serious rebellions from the Delian League occurring about Thrace. Unlike the revolts in Caria, Athens could not simply ignore this unrest. The insurrections here represented a more significant loss of about 40 talents out of a total collection of 350.

THE PELOPONNESIAN LEAGUE CONGRESS

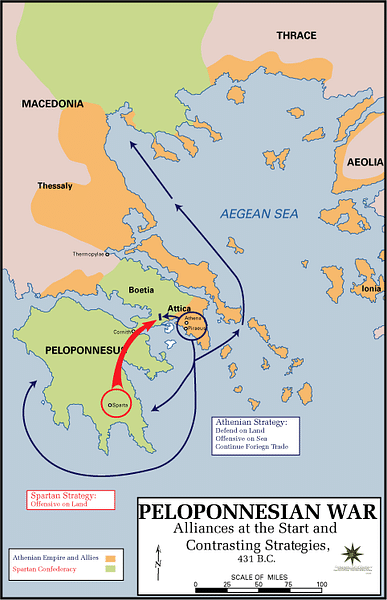

The developments in Sybota and Poteidaia prompted Corinth to gather allies and go to Sparta. The Athenians sent ambassadors to appeal. Historically, the Spartans proved not swift "to enter upon wars unless compelled to do so" (Thuc. 1.118.2). By 432 BCE, however, Corinth and Megara, as well as Aegina and Macedon, all desired war against Athens. The Corinthians and Athenians made their cases. King Archidamus of Sparta cautiously argued against: "Complaints on the part of poleis or individuals can be resolved, but when a whole alliance begins a war whose outcome no one can foresee, for the sake of individual interests, it is most difficult to emerge with honor" (Thuc. 1.82.6). The Ephors called for a vote: the Athenians had violated the Thirty Year's Peace.

King Archidamus' warning proved prophetic. The war would not exist simply between Athens and Sparta but between the Peloponnesian and Delian Leagues. It would prove a war for all of the Hellenes like no other, not between individual poleis for small and precise reasons but rather between two great alliances over a multitude of competing and disparate interests.

The Spartan Assembly nonetheless declared the Treaty broken. This required King Archidamus to summon the Peloponnesian League to hear the growing list of complaints against Athens, and Sparta's allies quickly voted for war. The majority of them simply had faith in the supremacy of the Peloponnesian army and predicted quick victory. King Archidamus further advised that they should first prepare for the next couple of years, and he convinced the allies to send three separate embassies to the Athenians. Although the Peloponnesian League did not make an appeal to arbitration (as required by the Thirty Years Peace), negotiations between King Archidamus and the Athenian Ekklesia continued for months.

Thebes ultimately forced Sparta's hand. Expecting Athens to invade Megara and secure the Attic southern border, the Thebans attacked Plataea to hold the northern border – an open violation of the Thirty Years Peace and the first clear act of war. Although the attack ultimately failed, King Archidamus gathered the Peloponnesian forces in the Isthmus of Corinth. He made one final bid for concessions. When the Athenians refused, he finally (and reluctantly), led the Peloponnesian army into Attica launching a war, he predicted, that they would leave to their sons. History proved Archidamus correct.

THE TWO GREAT LEAGUES ON THE EVE OF WAR

The two great alliances of Ancient Greece finally stumbled into a massive clash of arms, which resulted from a cascading chain of events. A relatively insignificant civil war that had begun in the remote and strategically unimportant Corcyran colony of Epidamnus became the catalyst. That civil war soon brought a series of competing alliances amongst various poleis into open conflict.

Corinth feared any resulting Athenian-Corcyran alliance overwhelmed the still formidable Corinthian navy, while the trade embargo of Megara, the critical polis between Corinth and Athens that resided in the middle of the main route between Attica and the Peloponnese, markedly discouraged pro-Spartan allegiances. The Spartans thus came to fear what the Confederacy of Delos represented: the unprecedented success of Ionian culture, symbolized by a radical democracy, an immense fleet, majestic buildings, grand festivals, flowering populations, spreading colonies, and a still growing alliance that might take hold within and eventually overwhelm the Peloponnese.

By the start of the Peloponnesian War, the Delian League had come to operate with naked aggression and repression. On the one hand, Persia had all but disappeared as a threat. On the other hand, many poleis protested that Athenian rule had severely restricted the liberty of the Delian League's members. Athens had also engaged in administrative and judicial interference, repeatedly demanded compulsory military service, exacted monetary payments, openly confiscated land, and attempted to impose uniform standards.

The Delian League now engaged in a form of open, hard imperialism. It not only unilaterally entered into alliances which affected all member poleis, not only interfered with the internal mechanisms of member poleis but had also transferred jurisdiction of the allied poleis to Athens and thus treated them all as honorary colonists.

This article is part of a series on the Delian League:

- The Delian League, Part 1: Origins Down to the Battle of Eurymedon (480/79-465/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 2: From Eurymedon to the Thirty Years Peace (465/4-445/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 3: From the Thirty Years Peace to the Start of the Ten Years War (445/4–431/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 4: The Ten Years War (431/0-421/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 5: The Peace of Nicias, Quadruple Alliance, and Sicilian Expedition (421/0-413/2 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 6: The Decelean War and the Fall of Athens (413/2-404/3 BCE)