Thebes was the capital of Egypt during the period of the New Kingdom (c.1570-c.1069 BCE) and became an important center of worship of the god Amun (also known as Amon or Amen, a combination of the earlier gods Atum and Ra). Its sacred name was P-Amen or Pa-Amen meaning "the abode of Amen".

It was also known to the Egyptians as Wase or Wo'se (the city) and Usast or Waset (the southern city) and was built on either side of the Nile River with the main city on the east bank and the vast necropolis on the west. This position on the river is famously referenced in the biblical book of Nahum 3:8, when the prophet warns Nineveh of its coming destruction, claiming that not even the great Thebes "situated among rivers, the waters round about it" was safe from the wrath of God. The biblical name for the city is No-Amon or No (Ezekial 30:14,16, Jeremiah 46:25, Nahum 3:8) referencing its fame as a cult center for Amon (though this name is also associated with the city of Xois in Lower Egypt). The Greeks called it Thebai from the Coptic Greek Ta-opet (the name of the great Karnak Temple) which became 'Thebes' - the name by which it is remembered.

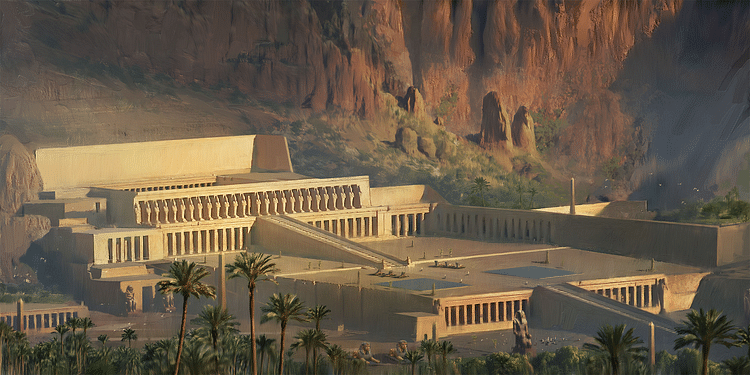

The city covered 36 square miles (93 square km) and is located approximately 419 miles (675km) south of modern Cairo. In the modern day, Luxor and Karnak occupy the site of ancient Thebes, and its surrounding area features some of the most important archaeological sites in Egypt such as the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens, the Ramesseum (temple of Ramesses II), the temple of Ramesses III, and the grand temple complex of Queen Hatshepsut.

Thebes was prominent by c. 3200 BCE owing largely to the rise in popularity of the cult of the god Amun and was known for its wealth and grandeur. In the 8th century BCE, long after Thebes had seen better days, the Greek poet Homer would still write famously of the city in his Iliad, "…in Egyptian Thebes the heaps of precious ingots gleam, the hundred-gated Thebes" and the Greeks would refer to the city as Diospolis Magna ('The Great City of the Gods').

During the Amarna Period (1353-1336 BCE) Thebes was the world's largest city with a population at around 80,000 people. At this same time, Akhenaten moved the capital from Thebes to his custom-built city of Akhetaten to dramatically separate his reign from his predecessors; his son, Tutankhamun, returned the capital to Thebes once he took the throne. The powerful priests of Amun consolidated their power to the point where, during the 20th Dynasty (c. 1190-1069 BCE) they were able to reign as pharoahs from the city.

Thebes continued as an important cult center and place of pilgrimage throughout Egypt's history, even after the capital was moved to Per-Ramesses (near the older city of Avaris) by Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE). During the Ramessid Period the priests of Amun ruled from Thebes while the pharaoh governed from Per-Ramesses. The city continued to grow in grandeur, especially the Temple of Amun, throughout this time. It was sacked by the Assyrians in 666 BCE, rebuilt, and finally destroyed by Rome in the 1st century CE.

Early Thebes

In the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2316-2181 BCE) the city was a minor trading post in Upper Egypt, which was controlled by local clans. During the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) the kingship was centered in Memphis until the rulers moved the capital to Herakleopolis. They were just as ineffectual there, however, as they had been in the old capital and this encouraged the local magistrates at Thebes to rise against the central government. The city began to grow more powerful under the leadership of powerful governors such as Intef I (c. 2125 BCE), Mentuhotep I (c. 2115 BCE) and Wahankh Intef II (c. 2112-2063 BCE) who established themselves as royalty. Wahankh Intef II even declared himself the true king of Egypt in opposition to the kings at Herakleopolis.

The Theban rulers waged war with the kings of Herakleopolis for supremacy and to unite the land under one rule. Mentuhotep II (2061-2010 BCE), a Theban prince, finally prevailed in c. 2055 BCE defeating the Herakliopolitan kings and uniting Egypt under Theban rule. The victory of Mentuhotep II elevated his gods and, chief among them Amun, above those of Lower Egypt. This deity grew in stature from a local god of fertility to the supreme being and creator of the universe.

Thebes itself was thought to have been formed by the hands of Amun, drawn up from the Nile's waters, just as the primordial mound of the ben-ben rose from the swirling waters of chaos at the creation of the world. In the original creation story, the god Atum or Ra stands upon the ben-ben and begins the work of creation. Amun was a combination of Atum, the creator god, and Ra, the sun god and, as this supreme lord had stood on the first dry earth at the beginning of creation, Thebes was considered his sacred place on earth and, perhaps, the original ben-ben on which he stood at the beginning of time.

The veneration of Amun gave rise to the trinity known as the Theban Triad of Amun, Mut, and Khons (also known as Khonsu) who would be worshiped in the city for centuries. Amun represented the sun and the creative force; Mut was his wife symbolized as the sun's rays and the all-seeing eye; Khons was the moon, son of Amun and Mut, known as Khons the Merciful, destroyer of evil spirits, and god of healing. These three deities of Upper Egypt were drawn from the earlier gods Ptah, Sekhmet, and Khons of Lower Egypt who continued to be worshiped under their original names in Lower Egypt but whose attributes were transferred to the Amun, Mut, and Khons, deities of Thebes.

The popularity of these gods led directly to Thebes' development, wealth, and status. Construction of the Temple of Karnak, dedicated to the worship of the triad, was begun around this time (c. 2055 BCE), and the temple would continue to grow in size and grandeur over the next 2,000 years as more and more details were added. It remains the largest religious structure ever built in the world. The priests of Amun, who administered the rites of the temple, would eventually grow so powerful they would threaten the authority of the pharaoh and, by the Third Intermediate Period (1069-525 BCE) the priests of Amun would rule Upper Egypt from Thebes.

The Hyksos

Thebes grew in status during the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1532 BCE) when the Theban princes stood against the mysterious Hyksos rulers of the Delta region. The Hyksos were a people of unknown origin and ethnicity (though many theories have claimed to be able to identify them) who either invaded Egypt or migrated into the region and steadily took power. They were firmly in control of Egypt by c. 1650 BCE and were regarded by later Egyptian historians as oppressive foreigners even though evidence suggests they introduced many innovations and improvements to the culture (the chariot among the more notable).

The Thebans and the Hyksos abided by a truce which forbade hostilities but did not guarantee any amicable relations between the two. The Hyksos would sail past Thebes to trade with the Nubians to the south and the Thebans would ignore them until the Hyksos ruler Apophis (also known as Apepi) insulted Ta'O of Thebes in 1560 BCE and the truce was broken. The Theban armies under Ta'O attacked the Hyksos cities. When Ta'O died in battle his son Kamose took command of the armies and razed their stronghold of Avaris. After his death, his brother Ahmose I took charge and captured the re-built city of Avaris, the Hyksos capital. Ahmose I drove the Hyksos out of Egypt and reclaimed the lands formerly ruled by them. Thebes was celebrated as the city which had liberated the country and was elevated to the position of capital of the country.

New Kingdom

With Egypt stabilized again, religion and religious centers flourished and none more so than Thebes.

With Egypt stabilized again, religion and religious centers flourished and none more so than Thebes. The shrines, temples, public buildings and terraces of Thebes were unsurpassed for their beauty and splendor. It was written that all other cities were judged 'after the pattern of Thebes'. The power and beauty of the great god Amun needed to be reflected fully in the holy city of Thebes and every building project sought to out-do the last in proclaiming the glory of this god.

The Tuthmosids of the 18th Dynasty (1550-1307 BCE) lavished their wealth on Thebes and made the Egyptian capital the most glorious city in Egypt. Work continued on the Temple of Karnak, but other temples and monuments rose as well. Most of the greatest monuments of ancient Thebes were either constructed, renovated, or improved upon during this period from c. 1550-1069 BCE with a brief interruption during the Amarna Period.

The Amarna Period

During the reign of Akhenaten (originally known as Amenhotep IV, 1353-1336 BCE) the priests of Amun at Thebes had become so powerful that they owned more land than the pharaoh and had more wealth than the crown. Scholars believe this situation may have prompted Amenhotep IV to adopt monotheism and proclaim the Aten - the sun disk - the supreme deity. In denying the existence of other gods, Akhenaten effectively cut off the source of the priests' wealth and power. The worship of all other gods except the Aten was outlawed, sacred icons and statuary destroyed, and the temples of Amun closed. Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten (meaning "successful for Aten"), and with his proclamation of the 'one true god, Aten', Thebes was abandoned for El-Amarna and the new city of Akhetaten.

If Akhenaten's true motive for religious reformation was to crush the priests of Amun and absorb their power, it worked; there was now only one true God whose will was interpreted by Akhenaten alone. While this new belief worked well for the pharaoh and the royal family, the people of Egypt were highly resentful. The worship of the many traditional gods of Egypt was an important aspect of everyday life throughout the country, and there were many, besides the priests, who lost their jobs once Akhenaten's monotheism became the religion of the land. Every merchant who sold religious artifacts and charms, every craftsman who made them, every scribe who wrote spells or prayers, was unemployed unless they turned their efforts to promoting the pharaoh's religion.

After Akhenaten's death, his son Tutankhaten ("living image of Aten") took the throne and changed his name to Tutankhamun ("living image of Amon") and restored the old gods and their temples. The capital was returned to Thebes, and a renewed interest in building projects began, perhaps to make amends to the gods who had been neglected, which produced even more glorious temples and shrines. The western shore of Thebes became a vast and beautiful necropolis in the years and centuries following and the mortuary complexes at Deir-El Bahri (like the one of Queen Hatshepsut) were awe-inspiring in their symmetry and grandeur.

Tutankhamun was succeeded by his general Horemheb (1320-1292 BCE), who believed that the old gods of Egypt were angered by the heretic king's insult to their honor. He encouraged building projects at Thebes (and elsewhere) and destroyed any iconography related to the worship of Aten or the royal family of the Amarna Period. He named Ramesses I as his successor who founded the 19th Dynasty.

Decline & Legacy

Ramesses II moved the capital from Thebes to a new site near the city of Avaris called Per-Ramesses where he built a grand palace to distinguish his reign from any which preceeded it. On a simpler level, he may have done this simply because there was nothing of significance he could add to the grandeur of Thebes and he was a pharaoh who needed to make an impression. Avaris now grew in prosperity and beauty as Thebes declined in power but this was a temporary situation. The priests of Amun, able to do as they pleased so far removed from the sphere of the pharaohs at Avaris, acquired significant amounts of land through which they amassed more and more wealth and greater power. By the time of the Ramessid Period they were ruling Thebes as pharaohs and the actual rulers at Avaris could do nothing about it.

The city declined during the Third Intermediate Period but still was impressive. The continued worship of the popular Amun and the legendary beauty of the city guaranteed Thebes a special place in the hearts of the Egyptians. The Nubian pharaoh Tatanami made Thebes his capital in the 7th century BCE, linking himself to the glory of the past, but his reign was short-lived. The Assyrian king Ashurbanipal invaded Egypt in 667 BCE and a second time in 666 BCE, completing the work he had left unfinished earlier, and sacked Thebes, driving Tatanami out of Egypt and leaving the city in ruins.

The Assyrians decreed that Thebes should be restored and rebuilt by Egyptian labor to compensate for their resistance to Assyrian rule. The city gradually recovered and worship of Amon continued there until the coming of Rome when it was destroyed by the Roman army in the 1st century CE. Afterwards it remained in ruins, populated only by a few people inhabiting the buildings which had been left vacant after the Romans moved on.

By the time of the historian Strabo (c. 63 BCE - 24 CE) the city was no more than a tourist attraction of ancient ruins and empty streets. Thebes retained its legendary status, however, and continued to be venerated by those who remembered its former glory. As the site of the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens, the great Temple of Karnak, and those of Luxor, Thebes continues as a vital link to ancient Egyptian culture and the vitality of its history into the present day.