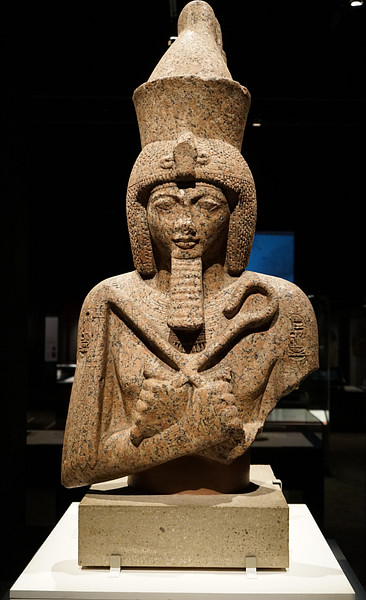

Pi-Ramesses (also known as Per-Ramesses, Piramese, Pr-Rameses, Pir-Ramaseu) was the city built as the new capital in the Delta region of ancient Egypt by Ramesses II (known as The Great, 1279-1213 BCE). It was located at the site of the modern town of Qantir in the Eastern Delta and, in its time, was considered the greatest city in Egypt, rivaling even Thebes to the south. The name means 'House of Ramesses' (also given as 'City of Ramesses') and was constructed close by the older city of Avaris.

The association of the new city with Avaris gave it instant prestige in that Avaris was already legendary by the time of Ramesses II as the capital of the Hyksos who had been defeated and driven from Egypt by Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE), initiating the period of Egypt's empire now referred to as the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE). The victory of Ahmose at Avaris, ending Hyksos control of the Delta, was greatly respected by the people of the New Kingdom, but even before that Avaris had been an important center for trade.

Associating his city with Avaris, therefore, was a clever choice of Ramesses II but hardly surprising in that he was well known for his skill in promoting himself and his grand projects. The size and grandeur of Pi-Ramesses, capital of Egypt, would make it far more famous than Avaris ever was, and its association with the long and glorious reign of Ramesses II ensured the memory of the city would live on long after it was abandoned toward the end of the New Kingdom of Egypt.

Pi-Ramesses in the Bible

The city is best known as the 'Rameses' from the biblical Book of Exodus 1:11: "So they put slave masters over [the Israelites] to oppress them with forced labor, and they built Pithom and Rameses as store cities for Pharaoh," but there is no evidence that the city was built by slave labor of any kind nor was it a 'store city' which held surplus grain or supplies. There is, in fact, no evidence whatsoever of a large Israelite community of slaves in Egypt at any time in its history, and the great cities and monuments were built by Egyptian laborers.

The association of Pi-Ramesses with the biblical Pharaoh of Exodus has also naturally suggested Ramesses II as that king. Ramesses II, however, left the most extensive and exacting records of any Egyptian monarch – there is literally no ancient site in Egypt which does not mention his name – and nowhere does he make any mention of Israelite slaves nor any of the events given in Exodus.

Exodus 12:37 claims that the Israelites left Egypt from the city of Rameses and that they numbered "about six hundred thousand on foot that were men, beside children." Numbers 33:3-5 also mentions Pi-Ramesses as the city the Israelites left Egypt from and mentions how the Egyptians were busy at the time burying the dead of their first-born whom God had killed in order to effect the release of his chosen people.

Although some scholars claim that Ramesses II would have omitted the story of the Exodus from his official records, because it cast Egypt in a poor light, it is far more probable that the Exodus story is a cultural myth which had nothing to do with Egypt's actual history and Pi-Ramesses was chosen for mention by the Hebrew scribe who wrote Exodus because its name would have been instantly recognizable. The link between Ramesses II and the heartless Pharaoh of the biblical narrative, as well as his city, is unfortunate in that it obscures the great achievements of the historical king and the Egyptian citizens who labored on his monuments and temples. Pi-Ramesses was built to exemplify the grandeur of Egypt under Ramesses II and its location chosen not only for ease of access to neighboring lands but because the locale of Avaris resonated with the people and the region had special meaning for the king.

Pi-Ramesses & the Battle of Kadesh

The area near Avaris was the childhood home of Ramesses II. His father, Seti I (1290-1279 BCE) built a summer palace there, and Ramesses II would have grown up exploring the region when he was not in school or following his father on military campaigns. Ramesses II was already named co-ruler with his father by the age of 22 and was leading his own successful campaigns into Nubia before coming to the throne in 1279 BCE. At some point, prior to 1275 BCE, he had his new city built, although some scholars suggest that construction actually began under Seti I who expanded on his palace. Whenever it was founded, it served as the launching point for the military expedition which Ramesses II himself always considered his greatest victory: The Battle of Kadesh.

Kadesh, in Syria, was an important trade center which had changed hands between the Hittites and Egyptians a number of times. Seti I had taken it from the Hittites, but they had seized it again under their king Muwatalli II (1295-1272 BCE). Ramesses II had already taken Hittite territory and scattered their defense in Canaan and so now turned his attention to Kadesh.

Preparations for the campaign began in Pi-Ramesses at least by early 1275 BCE. While Ramesses II consulted his oracles and advisors for auspicious omens, he had the entire industrial military complex of his city at work making arms, training horses, equipping soldiers, and building chariots. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson describes how, although ancient descriptions of Pi-Ramesses emphasize the beauty of its palaces and parks, the city also served in the war effort:

One of the largest buildings was a vast bronze-smelting factory whose hundreds of workers spent their days making armaments. State-of-the-art high-temperature furnaces were heated by blast pipes worked by bellows. As the molten metal came out, sweating laborers poured it into molds for shields and swords. In dirty, hot, and dangerous conditions, the pharaoh's people made the weapons for the pharaoh's army. Another large area of the city was given over to stables, exercise grounds, and repair works for the king's chariot corps...In short, Pi-Ramesses was less pleasure dome and more military-industrial complex. (314)

Ramesses II's battle with Muwatalli II at Kadesh was his most famous victory, which he celebrated through an account known as the Poem of Pentaur and another called the Bulletin. In these versions of the event, Ramesses II is every inch a warrior-king who leads his army to victory against overwhelming odds. The account of Muwatalli II, however, claims the same for the Hittite forces.

The Hittite account was unknown until the middle of the 19th century CE when European archaeologists were excavating Mesopotamian and Anatolian sites on a larger scale than ever before. Cuneiform tablets began to turn up in these digs which contradicted the version of history – in many areas – held up to that time. Prior to these excavations, the story of the Great Flood, Noah's Ark, and many other biblical narratives were thought to be original works and the Bible itself considered the oldest book in the world. After the Mesopotamian finds, scholars realized they had been missing some extremely important pieces of information in constructing the history of the world and Muwatalli II's account was among them.

Recent scholarship is fairly unanimous in agreeing that The Battle of Kadesh was more of a draw than a victory for either side. Muwatalli II still held the city but had failed to crush Ramesses II's army as he had wanted, and Ramesses II had driven Muwatalli II's army from the field and inflicted heavy casualties but had not taken the city. In Ramesses II's account, however, the victory for the Egyptians was complete and he was the king who had made it happen.

Grand City of Canals & Temples

Following Kadesh, Ramesses II would never lead another great military campaign; but that does not mean he did not commission them, and his reign is marked by decades of successful diplomatic and military victories, economic prosperity, and social stability. The reign of Ramesses II was so prosperous and so long, in fact, that when he died his people felt it was the end of the world; they had never known an Egypt without Ramesses II as pharaoh.

Ramesses II made Pi-Ramesses the most beautiful and opulent city in Egypt, rivaling the majesty of Thebes. An inscription regarding it reads:

His Majesty has built for himself a Residence whose name is 'Great of Victories'.

It lies between Syria and Egypt and is full of food and provisions.

It follows the model of Upper Egyptian Thebes and its duration is like that of Memphis. (Snape, 203)

The city was built on a series of earthen mounds known as geziras close to the Nile River. During the season of inundation, the Nile would overflow its banks and flood the area and Pi-Ramesses would be transformed into a city of islands amidst a swirling lake. During these times, the different geziras could only be reached by boat and ancient inscriptions (and archaeological evidence) indicate that the people moved easily around the city through an elaborate canal system.

Spread across six square miles (15 square km), and housing over 300,000 people, Pi-Ramesses became the most prosperous city of its day. It would have been the first city, other than Pelusium, any visitors from the east would have seen upon entering Egypt and was intended to impress. Every project Ramesses II commissioned was larger than life and created to glorify his name but his city seems to have been his crowning achievement.

Four large temples at each of the cardinal directions defined the city. To the north was the Temple of Wadjet, in the south the Temple of Set, east was the Temple of Astarte, and west the Temple of Amun. The choice of two of these particular deities is interesting in that Set and Astarte were both worshiped by the Hyksos at Avaris. It seems peculiar, at first, that Ramesses II would continue any tradition associated with the Hyksos since they had been cast as the supreme villains of Egyptian history by the scribes of the New Kingdom. Astarte, a Phoenician goddess, was long associated with Set as one of his consorts, however, and Set himself – although acknowledged as a god of chaos and darkness – was popular during the New Kingdom as a champion of the military. Ramesses II's father, Seti I, honored the god with his throne name.

Wadjet and Amun are logical choices in that Wadjet was one of the oldest goddesses of Egypt and the pre-eminent deity of Lower Egypt from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) onwards and Amun, by the time of the New Kingdom, was considered the most powerful of the gods. These four temples served as the 'anchors' of the city with the roads, canals, and other buildings constructed to reference each.

The western part of the city, near the Temple of Amun, was the royal district. The temple was actually dedicated to a composite god Amun-Ra-Harakhty-Atum who encompassed the power and characteristics of the creator-god Atum, the sun god Ra (also a creator-god), Ra-Harakhty (an amalgam of Ra and Horus, signifying the sun at the two horizons of sunrise and sunset), and Amun (the supreme king of the gods at the time). The grand palace of the king was also located here in proximity to the temple as were the administrative offices. Ramesses II's commemorative hall, built to commemorate his Heb-Sed Festivals (he celebrated two; one every 30 years) was said to be impressively adorned with statues, columns, and monumental statues of the king.

To the south, near Set's temple, were the military barracks, factories, a training ground, stables, the commercial district, and the two harbors which served the city. The stable complex was enormous, housing over 450 horses, and built with slightly slanting floors which allowed for waste to drop down into troughs. The training ground was a huge courtyard near the temple in which both soldiers and horses pulling chariots were put through maneuvers. In keeping with the grandeur and scope of the city, the bronze smelting factory was also the largest of its kind.

The eastern section, surrounding Astarte's temple, was the residential district as was the north, near Wadjet's temple. The houses were closely packed and, in keeping with traditional Egyptian custom, had the kitchen toward the back and open to the air, protected by a thatched roof. Each house probably also followed the traditional floor plan of a front parlor for receiving guests with the other rooms opening off of that one in a rectangular shape running toward the back. The homes of the more affluent had walled gardens at the back of their homes with brightly painted walls and a reflecting pool.

The main temple in the city was that of Amun, Ramesses II's patron god, which was said to be massive and included enormous statues of Ramesses II in his divine aspect. Ancient writers from the time and afterwards comment on the awe-inspiring grandeur of the city, the towering scope, and beauty of the canals and monuments. It would continue as the capital of Egypt under Ramesses II's successors but seems to have lost its luster further and further with each new king who came to the throne.

Decline & Fall

Although the inscription concerning it claims that Pi-Ramesses lasted as long as Memphis, this is not so. In its time, as noted, it rivaled Thebes in grandeur and power, but Thebes would continue long after Pi-Ramesses was a memory. The end of the city was signaled by the shifting of the Nile which silted the harbors so thoroughly that they became unusable. The eastern branch of the Nile changed its course, as it had done in the past, and the city could not adapt to this. As Steven Snape notes, this situation was common enough and Memphis had long ago grown used to it and made allowances in order to survive, but Pi-Ramesses was simply abandoned, largely dismantled, and moved south to the new city of Tanis with some monuments taken to Bubastis.

By around the year 1069 BCE, the central government was no longer effective and the high priests of Amun at Thebes were far more powerful than the king. Ramesses II was long dead by this time and his successors lacked his skills in leadership and administration. The last good pharaoh of the New Kingdom was Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE), but even he was not as impressive as Ramesses II and the so-called Ramesside Period of Egypt is one of decline. The kings who followed Ramesses III seemed weaker with each succession until, by c. 1060 BCE, the country had been ruled for about a decade by Thebes in the south and Tanis in the north, an era known as the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE).

When Pi-Ramesses was abandoned, the monumental statues, sections of temples, and other buildings were moved downstream in such quantity that, centuries later, archaeologists were sure that Tanis was Pi-Ramesses or, at least, was a city built during Ramesses II's reign. What remained at the site of the abandoned city was left to decay and, eventually, be reclaimed by the earth; the city center today is beneath the village of Qantir and, above ground, only the meager ruins of the Temple of Set, some foundations, and two stone feet from a statue of Ramesses II remain.