In ancient warfare open battles were the preferred mode of meeting the enemy, but sometimes, when defenders took a stand within their well-fortified city or military camp, siege warfare became a necessity, despite its high expense in money, time, and men. The Romans became adept at the art of siege warfare employing all manner of strategies and machinery to batter the enemy into submission. Five factors enabled the Romans to be remarkably successful at sieges: sophisticated artillery weapons, formidable siege towers, the engineering experience of fortification construction, superior logistics to ensure long-term supply, and mastery of the seas. Thorough preparation and the careful execution of well-laid plans were second nature to the Romans in warfare, and so when they applied these skills to sieges lasting months or years, they were virtually unstoppable.

Artillery

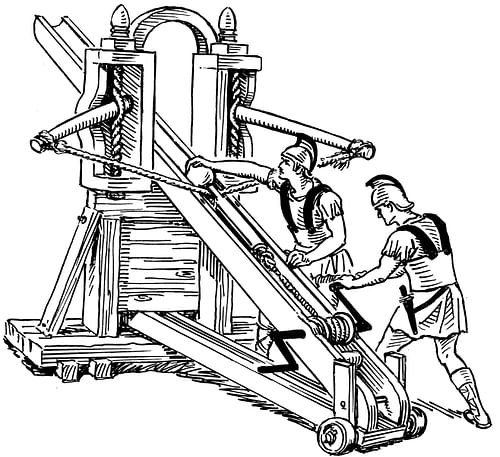

The Romans copied and improved upon the artillery weapons used by the Greeks, but they were not used in open combat, rather, they were reserved for siege warfare in order to pound the fortifications of cities and strike terror into the defenders. The Roman machines used animal sinews instead of horse hair to increase strength and torsion, allowing them to fire projectiles over several hundred metres. Metal parts (iron and bronze) replaced wood to increase strength, stability, firepower, and durability, and springs were covered in metal cases to decrease wear from the elements.

Stone throwers (ballista) had a single swinging arm and were known by the slang term onager (wild ass) for the violent kick when fired and scorpio (scorpion) because of its form. Stones were roughly circular and could weigh from 0.5 to 80 kilos, which allowed them to carve great chunks out of defensive walls and knock down fortification towers. Another type of artillery, much more accurate, was the carroballista or catapulta which fired heavy arrows, bolts or smaller stones and had two arms like a crossbow (and was also called a scorpio by some Roman writers). Bolts had iron heads and wooden shafts and fletchings and were easily capable of piercing armour. Another type of projectile was fireballs. Naturally, such weapons could be and were used to defend cities as well as attack them.

Legions probably had one artillery piece per cohort, although, some legions are described as having had 55 in some periods reflecting the fact that equipment was very much at the discretion of a particular commander. Artillerymen (ballistarii) were specialised troops exempt from normal fatigues, probably because they needed to practise with and maintain their machines. In addition, hundreds of wagons and mules were required to transport these machines and their ammunition to where they were needed. Some artillery machines were also mounted onto carts as seen in scenes on Trajan's Column.

Siege Engines

The Romans were a little slow to employ the siege engines or towers that the Hellenistic kingdoms had perfected. The siege of Utica by Scipio Africanus in 204 BCE was one of the first times they used them. They made adaptations, making their own towers smaller and so more manoeuvrable, for example. The towers also became more useful weapons in themselves when the Romans added battering rams, a boarding bridge, and interior fighting platforms which could carry both men and artillery pieces. Towers had wheels so that they could be constructed at a safe distance from the city and then moved closer when required.

Julius Caesar successfully employed a siege tower with 10 stories and bristling with artillery in the siege of Uxellodunum in Gaul in the 1st century BCE. Rolling the tower up a prepared embankment allowed Caesar to prevent the besieged accessing their fresh water spring. Sometimes towers looked so formidable that defenders surrendered rather than face them. This happened to Julius Caesar when he besieged Aduatuca, again in Gaul. Those defenders not overawed would strive to set fire to siege engines as they approached the walls but covering wooden parts in clay or soaking hide in vinegar could make the machines resistant to fire. Iron parts and shields were used for this reason too, but the extra weight meant that the towers were much less mobile.

Tactics

Sieges had significant advantages over open battles, as the historian P. Culham puts it,

they offered opportunities to kill combatants, terrorize populations, eroding their will to resist, and acquire strongholds all in one efficient operation with safely massed forces. (Campbell, 251).

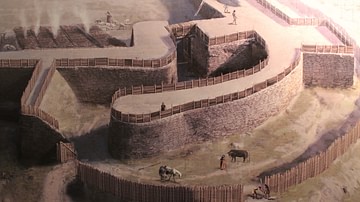

In a typical Roman siege, if an initial attack failed to bring immediate victory, forces were sent ahead to surround the settlement and prevent anyone escaping. At the same time, as very often ancient cities were also ports, they had to be blockaded by the sea as well as land. Accordingly, while ships blockaded the harbour, the main land army would build a fortified camp out of missile range from the city and preferably on high ground, which provided a good vantage point to observe inside the settlement and pick out key targets such as the enemy's water supply or secret entrances.

Then the siege might continue without any actual fighting in the hope that the defenders would eventually surrender from starvation, lack of water, or crushed morale. There was always the chance that a traitor might allow in the enemy by opening the city's gates, too. If all that did not work, then a more aggressive strategy was required. The besiegers might not always have things their own way, however, especially if they were attacking a city or fort in enemy-held territory. In that case camps would need reinforcing with wooden palisades and watch towers - both facing the enemy (circumvallation) and in the attacker's rear (contravallation). In order for the besiegers not to run out of supplies themselves, they also needed to maintain a well-defended supply route. The practice of building fortified camps now stood the Romans in good stead as they had the experience and tools to apply their engineering skills to attacking an enemy city.

Once an attack began, the defender's walls could be overcome by building a ramp (agger) up against them using trees, earth and rocks. Whilst this was being done the attackers would be protected by temporary covers such as a fire-proof wooden shelter (vinca) known as the tortoise or the more mobile convex wicker shield known as a pluteus. They would also be given a covering fire from artillery batteries and archers and could then scale the last part of the walls using ladders (scalae). Artillery fire might also rain down on the city from those mounted on ships in the harbour. The defenders could try to extend the height of the wall section under threat from a ramp (as happened at Jotapata when attacked by Vespasian in the 70s CE), build a second defensive wall behind the part under attack (as at Masada in 74 CE), or even add towers in the cat and mouse game of a long siege.

The next stage or alternative strategy was for the attackers to batter the walls or gates with heavy rams (arietes). These were suspended on a framework by chains and protected by hide or wooden covers. At the same time the siege towers, which might have their own ram, were rolled up to rise over the top of the fortifications. The rams of these engines were tipped with iron for maximum damage or even a hook (falx) to pull out the stone blocks of walls. Defenders would respond by lowering bags to cushion the walls or try to set fire to the towers as they approached closer. If the city was defended by ditches, then these would have to be filled before the towers could proceed. This was done by protecting those who filled in the ditches (using bundles of wood) with strengthened hide covers or the tortoise.

For very difficult cases, and rarely attempted, a mine (cuniculus) was tunnelled to collapse the walls from below. Defenders would respond by deepening their moat if they had one or digging down to the shafts and collapsing or flooding them. There were also cases of defenders releasing bees and bears into the tunnels to wreck whatever havoc they could. A more common and successful form of mining was to remove a specific section of a wall's foundation so that it would collapse. Defenders could also try to undermine the siege ramps and towers by tunnelling themselves.

The first soldiers to break through the enemy defences were richly rewarded, if they managed to beat the odds and survive, that is. If a breach was made then infantry could follow up, protecting each other by using their shields in the famous testudo (tortoise) formation. Of course, the defenders threw everything they could down on the attackers such as burning oil, burning pieces of wood, rocks, and jars of stinging insects.

Once inside, then bloody hand-to-hand street fighting would follow with the defenders secure in the knowledge that, once conquered, only the women and children could hope to survive, sold into slavery. An example had to be set of the futility of prolonged resistance and so the treatment of the defeated was often harsh and without mercy. For the same reason it was very unusual for a Roman army to lift a siege, once started. Rare failures are Julius Caesar's blockade of well-fortified Gergovia, capital of the Arverni, and Mark Antony at Praaspa, after he was forced to give up for lack of supplies. Otherwise, siege warfare, when conducted, was pursued for as long as it took to bring the city's fall and Roman victory.

Famous Sieges

One of the longest Roman sieges was the attack on Carthage in the Third Punic War between 149 and 146 BCE. The massively fortified city resisted until Scipio Africanus the Younger built a comprehensive siege wall and systematically attacked the weaker harbour walls with siege engines. Carthage finally fell and was completely destroyed. In 133 BCE Scipio, this time, lay siege to Numantia in Spain by building a ditch and stone wall punctuated by towers around the entire town.

A notable Roman siege was carried out by Julius Caesar at Alesia in 52 BCE, more strictly speaking a blockade, where he built a double circumvallation measuring 35 km. This wall was built using ramparts topped by wooden palisades punctuated by towers and protected by a 6.5-metre wide moat, a 3.2-metre wide and 1.5-metre deep ditch, 2 ditches filled with sharpened sticks (cippi), five rows of logs with iron spikes (stimuli), trap-pits (lilia), and 23 forts. Unable to break this stranglehold, eventually Vercingetorix was forced to surrender.

Caesar also attempted a rare mining tactic in the siege of Massilia (Marseille) in 49 BCE but had to abandon the effort. In 70 CE Titus besieged Jerusalem, amazingly constructing a seven kilometre siege wall in a mere three days. Masada was besieged, again by Titus, in 74 CE when the Romans built a massive 225-metre long and 75-metre high ramp level with the top of the city walls, the remains of which can still be seen today. The ramp allowed a metal-protected siege engine to get close enough to batter a hole in the seemingly impregnable fortress. Hatra in Mesopotamia was a rare case as it was besieged by Trajan (116 CE) and Septimius Severus (195-8 CE) but both times the siege was abandoned due to the strength of the city and the vast resources required to break it.

Other sieges were carried out in Sicily, Greece, and many forts in ancient Britain. Conversely, the Romans were hardly ever besieged themselves. Two rare cases were the siege of Sabinus' camp near Jerusalem in 4 BCE and that of Philippopolis in 250 CE by the Gothic king Cniva. The Sasanids were quick to learn the Romans siege strategies when they managed to capture their equipment and train themselves using Roman prisoners. In 256-7 CE they famously besieged the Romans at Dura Europos in Syria. For the most part, though, Rome's enemies lacked the resources and equipment to conduct siege warfare. Although the empire eventually crumbled the last legacy of Roman siege warfare was that many of their innovations in machines and defensive fortifications would be revived with great success in the medieval period.