Marie Durand (c. 1715-1776) stands apart in French Protestant history for her courage in the struggle for freedom of conscience. She was imprisoned for 38 years in the Tower of Constance at Aigues-Mortes in the south of France, liberated in 1768, and returned to her natal village where she died in 1776.

Protestantism in France

The 16th-century Protestant Reformation initiated centuries of conflict in a nation known as the eldest daughter of the Catholic Church. In just a few decades, the Reformation's influence in France "threatened the perception of nation forged by both king and subjects, because the king's own coronation oath required him to protect and defend his realm and his subjects from heresy" (Holt, 23). The Catholic religion and monarchy were united in their desire to preserve the status quo and prevent any challenges to their authority. Conflict was inevitable. The massacre of Protestants in Vassy in March 1562 by the Duke of Guise foreshadowed the bloodshed which would follow in the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598). At stake was the status of the Reformed religion in the kingdom. The intermittent wars and truces ended only when Henry IV (r. 1589-1610) converted to Catholicism.

Henry IV of France and the Edict of Nantes in 1598 provided a measure of religious freedom for Protestants while preserving the position of the Catholic Church. Protestants retained territorial possession of strongholds in more than 100 cities in France, including La Rochelle, Saumur, Montpellier, and Montauban. After Henry's death at the hand of an assassin, the protections enjoyed by Protestants began to unravel under his son and successor, Louis XIII (r. 1610-1643) and were removed with Louis XIV and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) largely based the Revocation on the fiction that all Protestants had converted to Catholicism. The Protestant religion was outlawed and authorities made attendance at the Mass and catechism mandatory. For the stubborn and non-compliant, there were different means of pressure – fines, lodging troops in homes, the king's galleys for men and prison for women caught at unauthorized gatherings. France had prisons scattered throughout the kingdom. In the north, the châteaux of Guise and Ham; in the west, at Saint-Malo, Saumur, Angers, Niort, and Angoulême; in the south, at Carcassonne, Ferrières, and Aigues-Mortes. When more space was needed, dissidents were transported to the Antilles from Languedoc. The regions of southeast France – Vivarais, Cevennes, Dauphine, and Bas-Languedoc – provided the majority of victims.

After the Revocation, Protestants were deported, imprisoned, condemned to the king's galley ships, or executed, and over 200,000 emigrated from France to places of refuge. Of those who remained, thousands were persecuted and charged with treason for practicing their faith. Many have had their stories told; many others have remained nameless in the shadows.

Marie Durand's Early Years

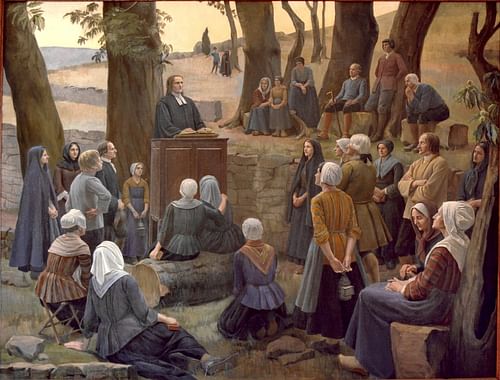

Marie Durand was born in 1715 in the hamlet of Bouchet-du-Pranles, in the Vivarais region of southern France, the daughter of Étienne and Claudine Gamonet. The Gamonets were a deeply religious Protestant couple, forcefully converted to Catholicism following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Their children were compelled to attend Mass and catechism and received Protestant instruction in secret. Marie's older brother Pierre assisted Antoine Court and the Church of the Desert and was later consecrated to the ministry.

On 29 January 1719, Étienne was arrested by the king's soldiers during a secret worship service in his home at which Pierre was preaching. Pierre escaped to Switzerland, his mother Claudine was imprisoned at the citadel of Montpellier, and their home was destroyed. Pierre later returned to France to preach and married Anne Rouvier, the sister of a friend who had been condemned to the king's galleys. The authorities again arrested Pierre's father in 1729 and imprisoned him for 14 years.

Imprisonment

When her brother fled into exile and her father was imprisoned, Marie found herself alone. Her solitude might explain her marriage around the age of 15 in April 1730. She married Mathieu Serre in secret, a man 25 years her senior, against the advice of her brother Pierre. Their time together was brief. Only a few months after their secret marriage both Marie and Mathieu were arrested. Mathieu was taken to Fort Brescou and released 20 years later in 1750. Marie was imprisoned in the Tower of Constance at Aigues-Mortes in southern France.

Upon her arrival, Marie joined 28 other women, mostly prophetesses from Languedoc and Vivarais. Imprisoned for being the sister of a pastor, she spent 38 years there in inhumane conditions. Apart from children born there, she was the youngest prisoner. Two years into her imprisonment, her brother Pierre was arrested and executed by hanging. Despite her great sorrow, she rose to lead the imprisoned women and wrote letters for herself and others to request help or to stay in contact with their families. These letters, of which about 50 have been found, have contributed to her renown in providing detailed information about life in the Tower of Constance. In her tower prison, there is an inscription which can be seen today engraved in stone – 'Resister'. Although there is no evidence that Marie wrote this, that single word captures the courage of women who suffered rather than deny their faith.

Life in the Tower of Constance

The Tower of Constance in the medieval town of Aigues-Mortes in the Languedoc-Roussillon region of southern France dates to the 13th century. The 33-meter-high tower was erected along with a château under Louis IX of France (r. 1226-1270). The origin of the name is contested but some believe the tower was named after Constance, daughter of Louis VI of France (r. 1108-1137). Aigues-Mortes was an insignificant, isolated port town surrounded by swamps. In 1574, the town came under Huguenot control, and in 1576, it was declared one of 8 safe havens for Protestants under the terms of the Edict of Beaulieu. The Edict of Nantes in 1598 preserved this special status. A Huguenot garrison was quartered there until its fall in 1622 after a siege led by Cardinal Richelieu (l. 1585-1642) during the reign of Louis XIII (r. 1610-1643). After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, the Tower of Constance was transformed into a royal prison for religious dissenters.

Beginning in 1715, the tower was reserved for women found guilty of attending illegal gatherings of the Church of the Desert. The women and their children born in the tower lived in wretched conditions of extremes of heat in summer and cold in winter. They occupied two vaulted rooms between walls several meters thick. During their years of imprisonment, they were supported with gifts from their friends in Switzerland and France. They worshipped regularly while their captivity served as an example to frighten others who might dare to disobey the royal edict forbidding Protestant gatherings.

From time to time, prisoners were freed upon conversion to Catholicism; some died in the tower, and others arrived to fill their ranks. Among the four new prisoners who arrived in 1737 was Isabeau Menet, a friend of Marie convicted of attending an illegal gathering with her husband, François Fialès. He was sentenced to the king's galleys and died in 1742. Isabeau suffered from a mental breakdown and was released to her family in 1749. Seven more women arrived from the Cévennes in 1742. In 1761, the last prisoner, Jeanne Darbon of Beaucaire, entered the tower and was liberated a month later.

Apart from those who recanted their faith or received a special dispensation, the first women were set free in 1762 thanks to a new military commander, and by 1766, only 11 prisoners remained. Prince Charles of Beauvau (l. 1720-1793) obtained the liberation of the remaining prisoners. Marie was freed on 14 April 1768, and the last three detainees, Suzanne Bouzigues, Suzanne Pagès, and Marie Roue were freed in January 1769. Marie returned to her natal village, Bouschet-de-Pranles where she lived with Marie Vey-Goutète, a companion in captivity. She died in July 1776, aged and infirm beyond her years.

Legacy

Thanks to the world of art Marie Durand has a visage, immortalized more than a century after her death by the painter Michel Leenhardt. In the 1892 painting Women Huguenot Prisoners in the Tower of Constance, Marie stands among weary women on the upper terrasse of the tower with her finger pointed heavenward in a posture of unshakeable submission to the divine will. Her letters provide information on conditions in the tower and her correspondence between France and Protestants in exile, yet little is known about Marie's daily life in confinement or how her faith was nourished and sustained. Her letters reveal little about her spiritual struggles during 38 years of imprisonment.

In any case, in the history of French Protestantism, Marie personifies peaceful resistance against religious oppression. Although her name today is found on a few schools and streets in the south of France, she has been largely forgotten by the French public and remains virtually unknown outside of France. Her memory, however, lives on as an example to those in the struggle for freedom of religion and conscience.