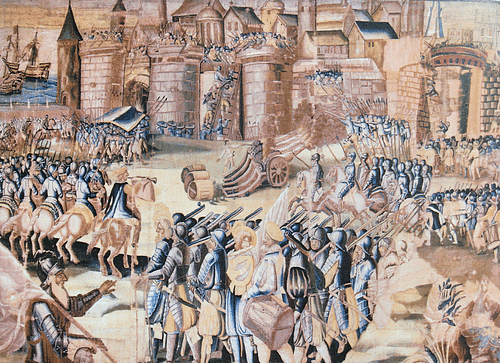

The French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) were a series of eight conflicts between Protestant and Catholic factions in France lasting 36 years and concluding with the Protestant King Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610) converting to Catholicism in the interests of peace. Although Protestant forces won the final battles, Catholicism triumphed, and France remained a predominantly Catholic nation.

The eight dates of the French Wars of Religion are:

- 1st War: 1562-1563

- 2nd War: 1567-1568

- 3rd War: 1568-1570

- 4th War: 1572-1573

- 5th War: 1574-1576

- 6th War: 1576-1577

- 7th War: 1579-1580

- 8th War (War of the Three Henrys): 1585-1589

- Armed conflict continued through 1598 when it was concluded by the Edict of Nantes.

Tensions had been rising between Protestants and Catholics since 1534 but the religious and political situation worsened after Henry II (r. 1547-1559) died from an injury. His son, Francis II of France (r. 1559-1560), crowned king at the age of 15, had been married to Mary, Queen of Scots (l. 1542-1587) who was the niece of Francis, Duke of Guise (l. 1519-1563) and his brother Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine (l. 1524-1574). Although Francis II was of age to rule on his own, his mother, Catherine de' Medici (l. 1519-1589) encouraged the Guise brothers to assume control as Francis II was inexperienced and sickly.

The House of Guise, devoutly Catholic, then exercised the power behind the throne and were hostile to the efforts of the Huguenots (French Protestants) who were advancing their vision in France. In March 1560, a group of Huguenots tried to kidnap Francis II to remove him from the influence of the Guise brothers. The plot, known as the Amboise Conspiracy, was discovered and anyone thought to be involved, as well as over 1,000 other Huguenots, were executed. In retaliation, Huguenots began vandalizing Catholic churches and rising tensions led to the Massacre of Vassy in March of 1562, in which Catholics killed more Protestants, starting the first war.

Conflict continued, with periods of armed peace between hostilities, until 1598 when King Henry IV, recognizing that France would never accept a Protestant king, converted to Catholicism (allegedly, with the famous line, “Paris is well worth a Mass”). His Edict of Nantes (1598), granting rights to Protestants in France while maintaining Catholic sovereignty, ended the French Wars of Religion (which had cost approximately 4 million lives) but did not address the underlying tensions which continued to erupt throughout the next century.

Affair of the Placards & Persecution

The Reformation launched by Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) in 1517 had reached France by 1521 but was not as enthusiastically received as it had been in the Germanic territories of the Holy Roman Empire where Luther and his followers were at work. Francis I of France, a devout Catholic, became king in 1515 but refrained from persecuting Protestant activists mainly because of his sister, Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1549), who was sympathetic to the cause and used her position as Queen of Navarre and influence over Francis I to protect them. Marguerite also intervened to reduce tensions by mediating between Catholics and Protestants to keep the peace.

Tensions between the two factions were present, but controlled, until October 17-18, 1534, when placards denouncing the Catholic Mass were publicly posted in Blois, Orleans, Paris, Rouen, and Tours – with one even appearing on the door of Francis I’s bedroom. Although this event, known as the Affair of the Placards, has been traditionally attributed to the Protestant Reformer Antoine Marcourt, some scholars believe it may have been organized by conservative Catholic authorities who had grown tired of Francis I’s leniency toward what they considered heresy and wanted to force him to act.

Francis I did so by initiating the persecution of Protestants and ignoring his sister’s pleas for restraint. Many Protestants, including Reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), left France at this time but those who remained were prohibited from gathering, preaching, or even casually discussing their views. Persecution under Francis I culminated in the Massacre of Merindol in 1545 in which thousands of the heretical sect of the Waldensians, who supported reform, were slaughtered and the survivors arrested and enslaved.

Francis I died in 1547 and was succeeded by his son Henry II who continued his policies. There was no restraining influence over Henry, as Marguerite de Navarre had been with Francis I, but his persecutions only drove Protestantism underground where it took hold and gained further support, even among members of the noble class such as Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Conde (l. 1530-1569) and Jeanne d’Albret (l. 1528-1572), daughter of Marguerite de Navarre, and Queen of Navarre after 1555.

Henry II died in 1559 from an accident incurred in a jousting match and his son, Francis II, became king at the age of 15 but, as he was inexperienced and often ill, his mother, Catherine de' Medici, asked the Guise brothers to assume control and instruct the young king. Francis and Charles of the House of Guise were already involved with the royal court since their sister, Mary of Guise (l. 1515-1560), had earlier arranged the marriage of her daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots, to Francis II. The Guise brothers quickly isolated the king from others at court, including Louis de Bourbon and the Admiral of France, Gaspard II de Coligny (l. 1519-1572) among others.

Amboise Conspiracy & Massacre of Vassy

This situation led to the Amboise Conspiracy of 1560 in which a group of Protestants planned to kidnap Francis II to remove him from the Guise’s influence. The plot was discovered and all those suspected of taking part in it were arrested and executed. Louis de Bourbon was among these and was slated for execution when Francis II died. His brother, Charles IX (r. 1560-1574) took the throne and his mother assumed direct control over him, sidelining the House of Guise and freeing Louis de Bourbon. In December 1560, Jeanne d’Albret publicly declared in favor of the Reformation, converting to Calvinism and in 1561, Catherine de' Medici appointed her Catholic husband Antoine de Bourbon (l. 1518-1562, brother of Louis) Lieutenant General of France.

Jeanne d’Albret outlawed Catholicism in Navarre while her husband was now responsible for controlling the simmering tensions between the traditional faith of France and what was seen as the heretical movement of the Protestants. The tension this caused in their marriage mirrored that of the country generally at this time which erupted in March 1562 in the Massacre of Vassy. Francis, Duke of Guise, was en route to Paris and near to the village of Vassy when he heard church bells ringing at a time when no Catholic Mass would be called. He sent his men to disperse what he recognized as a Protestant service and, when they met resistance, the massacre began leaving at least 50 Protestant worshippers dead. This event is considered the beginning of the French Wars of Religion.

First Three Wars 1563-1570

Both factions quickly blamed the other for the killings in propaganda campaigns which only fueled tensions. Louis de Bourbon seized Orleans in April 1562, declaring it now a Protestant city, and this encouraged other Huguenot leaders elsewhere to do the same. The first war raged for almost a year, during which Antoine de Bourbon was killed at Rouen and Francis, Duke of Guise was assassinated. The war was ended in March 1563 by the Edict of Amboise, brokered by Catherine de' Medici and supported by Jeanne d’Albret, but the underlying causes of the conflict were not addressed.

Both factions remained armed and hostile to each other between 1563-1567, only working together to drive the English (who had been invited by the Huguenots to help them) out of the port of Le Havre. The second war broke out in 1567 due to the Huguenot fears of Catholic reprisals against them for the first war and, although a peace was concluded in March 1568, it did not last long, and the third war was launched that summer. Battles and various atrocities continued throughout 1569 with many killed on both sides, including Louis de Bourbon, prince of Conde, who was executed after surrendering at the Battle of Jarnac in March 1569.

In the third war, Jeanne d’Albret, who had helped finance the first two, was actively leading the Huguenot forces as spiritual figurehead, propagandist, and financier. She again enlisted the aid of Protestant Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) in the cause and, with the help of Admiral de Coligny, made the city of La Rochelle a Huguenot stronghold. Neither faction could decisively defeat the other and the war dragged on until August 1570.

Hostilities ended with the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, negotiated by d’Albret and Catherine de' Medici, in 1570 and, in a gesture of reconciliation of the two factions, the women agreed their children – d’Albret’s Protestant son Henry of Navarre (later King Henry IV of France, l. 1553-1610 and de Medici’s Catholic daughter Margaret of Valois (l. 1553-1615) should marry. The marriage was set for August 1572 but d’Albret would never see it, dying of natural causes in June 1572.

St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre & Fourth War: 1572-1573

The wedding of Henry and Margaret drew large crowds, Protestant and Catholic, to Paris in August and tensions were running high already when, on 22 August 1572, Admiral de Coligny was shot in the street by an unknown assailant. De Coligny was only wounded and was brought to his apartments for care but Henry I, Duke of Guise (l. 1550-1588, son of Francis, Duke of Guise), argued for a preemptive strike against Protestants before they could begin reprisals for de Coligny.

On 24 August, Henry I’s supporters broke into de Coligny’s apartments, killed him, and threw his body out of a window, launching the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre which raged for the next five days and, elsewhere, for months, resulting in the deaths of thousands of Protestants and the fourth war. This conflict was concluded with the Edict of Boulogne in 1573 which granted immunity to Protestants for past “crimes against the state” but severely restricted their freedom of religious expression.

Fifth Through Seventh War: 1574-1580

Charles IX’s brother Henry, Duke of Anjou (the future Henry III of France, l. 1551-1589) had been elected King of Poland-Lithuania in 1573 but, when Charles IX died in 1574, returned to France and was crowned king. By this time, his younger brother, Francis, Duke of Anjou and Alençon (l. 1555-1584), had secretly sided with the Huguenots and, in 1575, joined the forces of Henry I de Bourbon (l. 1552-1588, son of Louis de Bourbon) and Henry of Navarre in the south. France was now divided between Catholic-controlled territories in the north and Protestants in the south with the Catholic faction drawing support from the pope in Rome and Phillip II of Spain and the Protestants supported by England, Germanic Protestants, and some Swiss cantons.

The fifth war lasted a year and was ended by the Edict of Beaulieu which restored religious rights to Protestants but angered the Catholics, especially Henry I, Duke of Guise, who felt it made too many concessions to “heretics”. Henry I formed the Catholic League, a coalition of powerful nobles supported by Phillip II of Spain, and started the sixth war in 1576 which ended with the Treaty of Bergerac (1577) that reversed the Edict of Beaulieu and again alienated the Protestants.

Protestant resentment, and both factions continuing to condemn each other as “heretics”, sparked the seventh war in 1579. These hostilities ended with the Treaty of Fleix in November 1580 negotiated between Henry III of France and Francis, Duke of Anjou and Alençon. Francis left France shortly afterwards at the invitation of the Dutch Protestant leader William the Silent (l. 1533-1584) to become monarch of the Netherlands and throw off the rule of Catholic Spain there. Francis arrived in the Netherlands in 1582, was given control of significant territories, but wanted more and so invaded Antwerp in early 1583. His troops were ambushed and slaughtered, and he returned to France in disgrace where he died in June 1584.

War of the Three Henrys: 1585-1589

Henry III of France had no son and so Francis had been next in line for the throne. After his death, this honor went to Henry of Navarre who was considered unacceptable as a Calvinist. Henri I de Guise and his Catholic League, with the support of Catholic Spain, forced Henry III to nullify Henry of Navarre’s legitimate claim as his heir and issue the edict in 1585 demanding that all Huguenots convert back to Catholicism or leave the country within six months. The Catholic faction still held most of the territory in the north while the Protestants held the south.

Armed conflict began in 1585 but escalated in 1587 (sometimes cited as the beginning of the eighth war) and, by 1588, Henri I de Guise had successfully turned Paris against Henry III for his failure to defeat the Protestants and unite France as a Catholic nation. Henry I, popular among the majority of Catholics in Paris, let the rumor spread that Henry III was trying to kill him and in May 1588 (the Day of the Barricades) Parisians revolted against Henry III, barricading the streets of the city to protect de Guise. Henry III fled to Blois and his mother, Catherine de' Medici, negotiated a peace with de Guise and the Catholic League.

In September 1588, Henry III called for a meeting at Blois where he had Henry I de Guise and his uncle the cardinal assassinated. The Catholic League was now taken over by Charles I, Duke of Mayenne (l. 1554-1611, the younger brother of Henry I de Guise), who denounced the king as a Protestant sympathizer and called for his execution. Henry III, with nowhere else to turn, joined forces with Henry of Navarre who began marching from the south toward Paris. In July 1589, Henry III was assassinated by a Dominican friar, Jacques Clement, who was following the directives of the Catholic League. As he lay dying, Henry III named Henry of Navarre his successor. The War of the Three Henrys was concluded, with only one left standing, but armed conflict continued.

Conclusion

Henry of Navarre was now legally Henry IV, King of France, but had no control over the northern and eastern parts of his kingdom. Between 1589-1593 he won a series of decisive battles against the forces of the Catholic League but could not take Paris which was heavily fortified against him. Recognizing that France would not accept a Protestant monarch, and understanding he could better advance the cause as king than by continuing the slaughter, he converted to Catholicism in 1593 and was crowned king in 1594.

In 1598 he issued the Edict of Nantes, formally ending the French Wars of Religion by mandating freedom of religion for both Protestants and Catholics, although Protestants were limited to practicing their faith in restricted regions and all outside of Paris. The Edict of Nantes ended the open conflict between the factions but, like all the other treaties and edicts issued since 1563, could do nothing to change people’s hearts and the factions continued hostilities, on a quieter, more personal scale, afterwards.

Henry IV was assassinated in 1610 by a Catholic zealot who felt he had betrayed the true faith and religious tensions would continue throughout the next century. The failure of the two factions to come to a mutual understanding contributed to France’s 1635 entry into the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), one of the most devastating conflicts in European history.