Women played a vital role in the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648) not only by supporting the major reformers as wives but also through their own literary and political influence. Their contributions were largely marginalized in the past, but modern-day scholarship has highlighted women's roles and established their importance in spreading the reformed vision of Christianity.

Prior to the Reformation, the lives of women were ordered by the Catholic Church, the patriarchal nobility, and their husbands or sons. Women in the Middle Ages held jobs and some even assumed control of the family business after their husbands' death, but their opportunities were still limited, with rare exceptions, to becoming a wife and mother or a nun. After the Reformation began, women found new freedoms – as well as uncertain futures – as monasteries and nunneries were closed, eliminating the option of monastic life, while also allowing women who had been forced to become nuns to now choose their own path.

The Reformation affected women's lives throughout Europe and beyond and, as it was not a cohesive movement, different Protestant sects regarded women in different ways. The followers of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) believed that a woman's place was in the home, caring for the children, and those who supported the views of Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) felt likewise, while the Anabaptists, who had emerged as their own sect from Zwingli's reforms, elevated women's status to positions of authority as ministers and prophets.

Even within more restrictive Protestant sects, however, women still found they had more of a voice and greater opportunities than before. Luther's wife, Katharina von Bora, was a former nun who married, raised children, brewed her own beer, and ran a farm, while Katharina Schutz, wife of reformer Michael Zell (d. 1548), became far more famous than her husband for her written works. The Protestant Reformation encouraged literacy because, no matter the sect, the new teaching emphasized the importance of reading the Bible for oneself, and so girls were now allowed an education whereas, previously, educating women was considered a waste of time.

Ten Women of the Reformation

The ten women on this list are only a very small sampling of the many who contributed to the Reformation and are mainly drawn from the Lutheran and Reformed sects as their lives are among the best documented:

- Katharina von Bora (l. 1499-1552)

- Argula von Grumbach (l. 1490 to c. 1564)

- Anna Reinhart (l. c. 1484-1538)

- Katharina Schutz (l. 1497-1562)

- Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1549)

- Marie Dentiere (l. c. 1495-1561)

- Katharina von Zimmern (l. 1478-1547)

- Jeanne d'Albret (Joan III of Navarre, l. 1528-1572)

- Anna Adischwyler (l. c. 1504-1564)

- Olympia Fulvia Morata (l. 1526-1555)

These women did not suffer as greatly as many others who took a stand for their religious convictions but often endured hardships for their faith, refusing to compromise, even when doing so would have made their lives easier.

Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora (also known as Katherine Luther, l. 1499-1552) was a nun who wrote to Martin Luther in 1523 asking for his help in freeing her and some others who had converted to his teachings from their convent. Luther sent a merchant, Leonard Kopp, who regularly delivered goods to the convent, and he smuggled the women out in empty herring barrels. These women were then free to return home, marry, or do what they wished, but many of their families could not afford to take them back, and men were reluctant to marry former nuns. Luther found a place for all the women except Katharina who he then married in 1525. She instantly took over all of the practical matters of the household, including the finances, planted gardens, brewed her own beer for sale, and helped Luther in the formulation of his ideas. She also regularly contended with harsh criticism from Luther's enemies, who denounced the marriage of two former clerics who, according to Catholic tradition, were supposed to have remained celibate. After Luther's death in 1546, Katharina struggled to maintain their home but was forced to flee during the Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547) and died of an unknown disease in 1552.

Argula von Grumbach

Argula von Grumbach (nee von Stauff, l. 1490 to c. 1564) was born to an upper-class, highly devout, Catholic family in Bavaria who valued education. Her father ignored the Church's teachings discouraging education for women, and she was already reading and memorizing the Bible by age ten. She was a lady-in-waiting at court by age 16 where she continued to study the Bible, and in 1516, she was married to the noble Friedrich von Grumbach (d. 1530). In 1522, Argula read the works of Luther and Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) and converted to the Protestant vision. Her husband remained Catholic and, as she wrote frequently about her new faith, his colleagues encouraged him to break her hands or even murder her if he could not make her stop. He did neither, but their marriage seems to have suffered because of their religious differences. She is best known for her eloquent letter defending a young Lutheran teacher at the University of Ingolstadt who was arrested for heresy. The letter was quickly turned into a pamphlet, printed, and became a bestseller. She was regularly denounced as a whore and was shunned by many of her family and friends, but she continued writing, corresponding with Luther, and even traveling alone to preach on the new teachings until her death from unknown causes c. 1564.

Anna Reinhart

Anna Reinhart (also given as Anna Rheinhard, l. c. 1484-1538) was a young woman of Zürich known for her exceptional beauty who secretly married one John von Knonau in 1504 after his father forbade their relationship. When von Knonau's father learned of their marriage, he disinherited his son, who then joined the Swiss mercenaries to make a living. He returned from the wars in ill health and died, leaving Anna with a son, Gerold. When Huldrych Zwingli came to Zürich in 1519, he discarded the Church liturgy and began reading directly from the Bible, making him a popular minister. Anna was a member of his congregation, and he took an interest in helping her and her son. They were married in 1524, but in secret since Zwingli was a priest and was supposed to remain celibate. When news of their marriage broke, they were censured, and Zwingli responded by defending clerical marriages and the state of marriage in general as sinless. Anna supported and cared for Zwingli throughout their time together, arranging for bodyguards when he left the home and helping him proofread his translation of the Bible. After he was killed in the Kappel Wars in 1531, she was taken under care by his successor Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575) and his wife Anna until her death from illness in 1538.

Katharina Schutz

Katharina Schutz (also known as Katharina Zell, l. 1497-1562) was a well-educated Catholic of Strasbourg who was introduced to Luther's teachings by the priest Matthew Zell who became the pastor of her church in the city in 1518. Zell had rejected Catholic precepts for Lutheranism, and Katharina converted as well. She married Zell in 1523, one of the first women to marry a clergyman, and worked with him as an equal partner in advancing the cause of the Reformation. She was a prolific writer whose pamphlets became bestsellers, especially her work justifying clerical marriage. Like Argula von Grumbach, she was criticized by her enemies for neglecting her 'wifely duties' and acting 'against nature,' though she never faced the same level of opposition. When the German Peasants' War broke out in 1524, she and her husband worked together to try to stop the violence, and she regularly cared for the sick and poor of the city. After her husband's death, she continued writing, preaching, and welcoming refugees from Catholic persecution into her home. She was well-respected by both Luther and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) and continued in her care for others until dying of disease in 1562.

Marguerite de Navarre

Marguerite de Navarre (also known as Margaret of Navarre, l. 1492-1549) was the highly educated Queen of Navarre, wife of Henry II of Navarre (r. 1517-1555) and sister of Francois I (Francis I of France, r. 1515-1547). She was fluent in English, French, Hebrew, Latin, and Spanish and well-versed in classical literature. Her court was internationally renowned and, after her conversion to Protestantism, she influenced the Reformation in England through the translation of her poem Mirror of the Sinful Soul, which was condemned as heretical by the Catholic Church. Marguerite would have no doubt been persecuted for this poem and her other writings but for the protection of her powerful brother. She regularly interceded with him to release Protestants from prison or allow them to preach in France, and he did as she asked, even though he remained a devout Roman Catholic. She maintained a correspondence with Marie Dentière, John Calvin, and Philip Melanchthon, among others, and helped to establish the Reformation in France through her patronage of the arts, Protestant works, and protection of those who would otherwise have been arrested and executed as heretics.

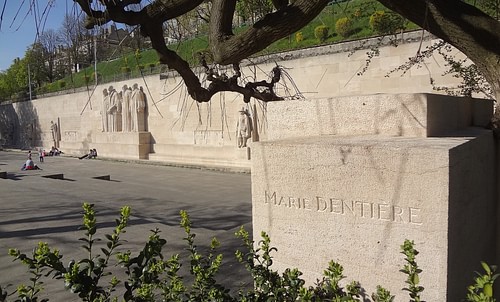

Marie Dentière

Marie Dentière (l. c. 1495-1561) was an accomplished writer and reformer in her own right who worked with her husband Antoine Froment (l. 1508-1581), Guillaume Farel (William Farel, l. 1489-1565), and John Calvin to establish the Reformation in Geneva and extend reformed teachings throughout Switzerland and France. She was a nun in modern-day Belgium and had become an abbess when she read Luther's works in 1524 and abandoned her position, fleeing to Strasbourg where she married a Reformed priest. After his death, she married Froment, and the two lived outside of Geneva. She wrote and anonymously published The War and Deliverance of the City of Geneva in 1536 advocating for widespread acceptance of Reformed teachings and equality for women, especially as clergy. Dentière rejected the patriarchal view that women were incapable of understanding, much less preaching, scripture, and cited female figures from the Bible as support for her claims. She encouraged Marguerite de Navarre to banish the Catholic clergy from France and supported the work of Calvin and Farel in Geneva until they distanced themselves from her due to her 'radical' views on women's equality. After her death, Froment faded from the movement, suggesting it was actually Dentière who was the reformer. She is the only woman whose name appears on the Reformation Wall monument in Geneva.

Katharina von Zimmern

Katharina von Zimmern (l. 1478-1547) was the abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey in Zürich for 30 years and the last before the monasteries were dissolved. She entered monastic life when she was around 13 and became abbess at 18. Under her authority, the monastery expanded, and she became one of the most powerful and well-respected women in the city. When Zwingli began preaching the Reformed vision in 1519, von Zimmern supported him, inviting him to preach at the monastery every Friday. After the First Disputation of 1523 between Zwingli and representatives of the Church, Zwingli's version of Christianity was accepted by Zürich, and in 1524, von Zimmern voluntarily surrendered Fraumünster to the city of Zürich to be put to other uses. Her advocacy of the Reformation ensured its peaceful adoption by the city council and the closure of the other monasteries without the kind of violence and bloodshed that accompanied such changes elsewhere. Afterwards, she married Eberhard von Reischach, and they had two children before von Reischach was killed in the Kappel Wars along with Zwingli. She died of natural causes at home around the age of 69.

Jeanne d'Albret

Jeanne d'Albret (Joan III of Navarre, l. 1528-1572) was the daughter of Marguerite de Navarre. She converted to Calvinism in 1560 and became the leader of the French Huguenots (French Protestants). She was well-educated, composing poetry and memoirs, and was influenced by her mother's religious convictions, entertaining them without embracing them. In 1555, she and her second husband Antoine de Bourbon (l. 1518-1562) became the rulers of Navarre, and one of her earliest acts was to call a conference of Protestant ministers to present their case. She officially converted to Protestantism on Christmas Day 1560 and outlawed Catholicism, banishing all Catholic clergy. Her actions contributed to the hostilities that erupted as the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) between Catholics and Protestants in which over 3 million people, including Antoine de Bourbon, died. Jeanne ruled alone afterwards and used her personal funds to finance the Huguenot forces. She was threatened by the pope, who also initiated plans to have her kidnapped and imprisoned or executed, but she remained true to her convictions even when Antoine, who had sided with the Catholics, threatened to divorce her. She concluded the peace through the marriage of her son Henry (l. 1553-1610, later King Henry IV of France) to Margaret of Valois (l. 1553-1615), daughter of King Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici (l. 1519-1589), who was later rumored to have poisoned her. She actually died of natural causes at home.

Anna Adischwyler

Anna Adischwyler (also known as Anna Bullinger, l. c. 1504-1564) was the wife of the reformer Heinrich Bullinger who succeeded Zwingli as head of the Reformed Church in Zürich after the latter's death in 1531. Her father died when she was eight years old, and her mother, who was ill and could not afford to raise her, turned her over to a local convent in Zürich, where she became a nun. The convent also served as a hospital where her mother became a patient. After the monasteries were dissolved in 1524, Anna (who had converted to Protestantism) and her mother remained behind, and she met Bullinger when he accompanied Zwingli's associate Leo Judd (l. 1482-1542) on a visit one day. Bullinger instantly fell in love with her and proposed marriage, but her mother, who remained Catholic, objected, and they had to wait until she died in 1529 to marry. Anna Bullinger not only supported her husband's ministry and vast responsibilities once he took over from Zwingli but also opened her home to refugees and the poor of the city as well as entertaining the leading reformers of the day when they visited Zürich in addition to raising her eleven children. She was praised as a selfless and devoted Christian, working tirelessly to provide comfort and shelter for others, and proved this by caring for her husband when he was stricken by the plague, even though she was sick herself. She died of the plague in 1564.

Olympia Fulvia Morata

Olympia Fulvia Morata (l. 1526-1555) was a poet, scholar, and writer who also served as companion and tutor to the princess Anna d'Este (l. 1531-1607). She was born in Ferrara, Italy, and her literary father ensured she was well-educated. She had read the classical works and was fluent in both Greek and Latin by age 12, prompting her selection as companion-at-court to Anna d'Este. Around 1546 she converted to Protestantism, and after Anna d'Este left to get married, Olympia returned home to care for her ailing father. After his death, she cared for her mother while studying philosophy and the Bible, writing commentaries and dialogues, and corresponding with other scholars including Melanchthon. Around 1550, she married the physician Andreas Grundler and followed him to his hometown in Schweinfurt, Bavaria. At this point, she had already translated the psalms into Greek and seems to have written a number of important commentaries on philosophy and religion, which were not yet published. In 1553, the renegade noble Albert Alcibiades pillaged Schweinfurt as part of his policy of securing sacred relics, and the couple had to flee with only their clothes, leaving many of Olympia's works behind, which were lost when the city was burned. They found refuge in Heidelberg, where they lived for a year until Olympia died, possibly of plague, in 1555. Her husband had saved what works he could, and they were later published at Basel in three editions between 1558 and 1580. They are regarded as some of the greatest philosophical works of the Reformation period.

Conclusion

There are many others whose contributions were considered important enough to note but with few details given. One famous example of this is Idelette de Bure (l. 1500-1549), wife of John Calvin. Idelette was a young widow with two children when she married Calvin, and when she died, he wrote that she was his best friend who faithfully encouraged his ministry. She also cared for him constantly during his bouts of illness. Another interesting figure is Mary Phyllis (b. c. 1577), who came from Africa to London as a child and embraced the Protestant vision. She is among the first known Protestants of color in Europe, but little else is recorded of her life save that she was an important member of her congregation.

Several Anabaptist women are also noted in the records but frequently only regarding their arrest and execution. Aefgen Listincx (d. 1538), for example, was an Anabaptist prophet who was instrumental in establishing the sect's control over the German city of Münster in 1534-1535. The Anabaptists were denounced as dangerous radicals by both Catholics and other Protestant sects, and after the city fell to their forces in 1535, she was arrested and burned as a heretic in 1538. These women, and many others, contributed greatly to the Reformation, establishing themselves as the equals of men and encouraging other women to follow their example.