Marie Dentière (l. c. 1495-1561) was a French theologian, writer, and street preacher who advanced the cause of the Protestant Reformation in Geneva, Switzerland. Her written works were controversial primarily because she was a woman and were suppressed during her life and largely ignored until the 19th century.

Dentière and her second husband, Antoine Froment (l. 1508-1581), worked alongside John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) and Guillaume Farel (William Farel, l. 1489-1565) to establish the Reformation in Geneva and advance its vision elsewhere. Froment was an early advocate of reform in Geneva but was later overshadowed by his wife's powerful personality and public advocacy of women's rights and place in the Reformation at a time when women were not allowed to preach or teach men. She was eventually censured by Calvin and Farel, who distanced themselves from her and Froment, and she was denounced for 'perverting the people from devotion' by the Catholic nun and writer Jeanne de Jussie (l. 1503-1561), secretary of the convent of Poor Clares in Geneva.

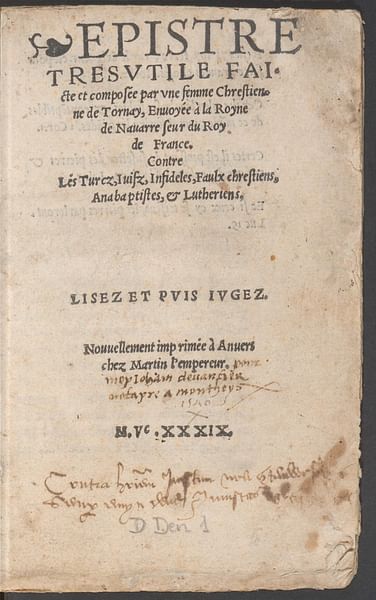

She is best known for her works The War and Deliverance of the City of Geneva (1536) and A Very Useful Epistle (full title: A Most Beneficial Letter, Prepared and Written down by a Christian Woman of Tournai, and Sent to the Queen of Navarre, Sister of the King of France, Against the Turks, the Jews, the Infidels, the False Christians, the Anabaptists and the Lutherans, 1539) as well as for the preface she wrote to Calvin's A Sermon on the Adorning of Women (1555). Her works, except for the last, were rejected by the patriarchy of Geneva, and her advocacy resulted in a difficult marriage and her estrangement from the Reformation's leaders in the city.

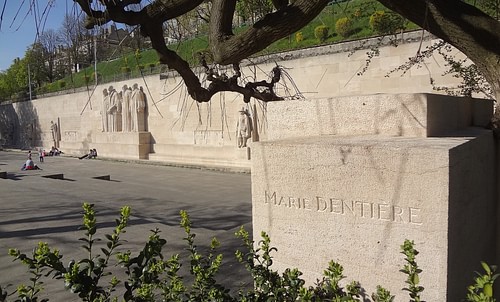

Froment seems to have preserved her works after her death, but they continued to be ignored by historians until the 19th century. She is the only woman whose name appears on the Reformation Wall monument in Geneva, unveiled in 1909, but this was only added in 2002. Today, she is recognized as one of the most significant voices of the Reformation, and Marie Dentière's A Very Useful Epistle is frequently anthologized.

Early Life and Conversion

Dentière was born in Tournai, then part of France, now in Belgium, to an upper-class family. Scholar Kirsi Stjerna comments on her early years:

Very little is known of Marie's life, with no certainty even about her birthday. She was born around 1495 in Tournai, France, to the noble family of Jerome d'Ennetieres and died around 1561. Even the spelling of her family name in documents has been irregular, d'Ennetieres and Dentière being the most frequent spellings while D'Entiere is also relatively commonly used. In 1521 she joined an Augustinian convent at Tournai, where some sources suggest she may have held a superior office. (135)

The date of Dentière's entrance to the convent is disputed, with some sources citing 1508, which makes more sense as nuns frequently began their tenure as young girls but, also, because by 1521 the works of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) were already exerting significant influence, and it was Luther's writing that converted Dentière to the Protestant vision. If she did hold a high office (which seems likely based on the later account by de Jussie), she would have had to have entered the convent prior to 1521 because she renounced Catholicism and fled the convent for Strasbourg in 1524.

Strasbourg was a popular haven for Protestants at this time, and she spent four years there before marrying a Reformed priest, Simon Robert, in 1528. By this time, she had met a number of important reformers including Matthew Zell (l. 1477-1548) and his writer-wife Katharina Zell (née Schütz, l. 1497-1562), John Calvin, William Farel, Antoine Froment, and Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551). It is suggested by Stjerna that Katharina Zell's Defending Clerical Marriage (1524), as well as her other works, may have encouraged Dentière to begin writing herself.

Dentière and her husband worked closely with Farel and Froment, following their lead in preaching outside of Strasbourg. Farel left for Geneva in 1532 and spearheaded Reformation efforts there with Pierre Viret (l. 1511-1571) while Froment remained behind and supported the various ministries that had begun, including Robert's. Dentière and Robert would have five children before he died in 1533 and she then married Froment. The family then followed Farel's lead and moved to a suburb of Geneva in 1535.

Dentière & de Jussie

Froment became a popular preacher in Geneva at this time and was respected as the author of a Protestant history of the city, The Marvelous Acts and Deeds of the City of Geneva. He was soon overshadowed by the arrival of John Calvin, who, with Farel, began the large-scale conversion of the city to the Reformed vision. Part of the conversion effort was 'liberating' the nuns from their convents in which, according to the reformers, they had been imprisoned by false beliefs. The Convent of Saint Clare in Geneva was home to the order of nuns known as the Poor Clares who were sworn to chastity, enclosure within the convent, obedience to the Church, and poverty.

The women of the order, according to the work of Jeanne de Jussie, were perfectly content with their lives before the Reformation, which encouraged Protestant women to preach to the nuns to convert them, and, in time, male reformers also appeared, including Farel and Viret. Their first (and last) sermon at the convent was loudly denounced by the sisters of the order, with the prioress, who had been locked out of the room, beating on the doors and the nuns crying to drown out Farel's words. The two men left but, shortly after, sent Dentière with some other women to see if she could persuade them. Dentière had no more success than Farel and Viret, however, as explained by de Jussie:

In that company was one false abbess, wrinkled and of diabolical language, possessing a husband and child, named Marie D'Entiere of Picardy, who mixed herself up in preaching and in perverting the people from devotion. She placed herself among the sisters [who rejected her] but, because of the desire she had of perverting someone, she did not take note of these reproaches and said, "Alas, poor creatures! If only you knew how good it was to be next to a handsome husband, and how God considers it pleasing. For a long time, I lived in those shadows and hypocrisy where you are, but God alone made me recognize the abuse of my pitiful life, and I was brought to the light of truth. Considering with regret how I lived, for in these orders there is nothing but sanctimoniousness, mental corruption, and idleness…I took about five hundred ducats from the treasury of the abbey, and I left that unhappiness. Thanks to God I have five handsome children and I live wholesomely." (Wilson, 263)

For many women, the daily life of medieval nuns was a liberating option to marriage. As a member of an order, a woman could receive an education, learn various skills, and was freed from the direct dominance of a husband and the possibility of dying young in childbirth. Jeanne de Jussie, in her Short Chronicle (1535), rejects the reformers' efforts at 'liberating' women such as herself and calls them false Christians and enemies of the faith.

Although de Jussie and Dentière both advocate for the value of women as equal to, or greater, than men, they interpreted 'liberation' quite differently. De Jussie understood herself as having been freed by monastic life; Dentière felt the same for having rejected it. De Jussie's work presents a different perspective on the Reformation in Geneva from Protestant works which view it as a great cultural and religious achievement. To de Jussie, the Reformation destroyed the cultural cohesion of the city, and women like Dentière were the ones in need of 'saving', not the nuns of the convent.

Famous Works

Dentière disagreed and made her feelings known to de Jussie and everyone else in her 1536 work The War and Deliverance of the City of Geneva (full title: The War for and Deliverance of the City of Geneva, Faithfully Prepared and Written Down by a Merchant Living in that City), which presented a history of the city's "salvation from darkness" between 1532 (when Farel arrived) and 1536 (the year of Calvin's arrival). Comparing the people of Geneva to the Israelites in the biblical Book of Exodus, Dentière depicts the Reformation in the city as a holy war to free those held in bondage to false beliefs. Stjerna comments:

She boldly argued that the people's suffering had its origins in false preaching (as proven by the suffering of her fellow Genevans who were listening to false proclamations). She also predicted that any attempts to destroy the gospel and its proper proclamation would only have the counter effect of making the people yearn for more. In other words, good preaching was a necessity that could not be suppressed; there was a need for it among people and it would eventually cause changes and end the suffering in Geneva – just as had happened to the Israelites in the story of Exodus. (138)

The work advocated for the recognition of female preachers who were just as able to interpret scripture and teach others as men and denounced clerical celibacy as unbiblical and oppressive to both men and women. The piece was published anonymously and, at first, was attributed to Froment because of his earlier Protestant history and the title page attributing it to "a merchant living in that city". It was popular reading at first but quickly disappears from all accounts with no reason given. Scholars speculate, however, that it fell out of favor when it was found to have been written by a woman.

Dentière does not seem to have cared and continued her advocacy, which encouraged Calvin and Farel to distance themselves from her and her husband. In a 1537 letter, Calvin mocks Froment, and Farel accused Dentière of ruining her husband. Calvin and Farel continued to orchestrate the Reformation in Geneva until they were asked to leave by the town council in 1538 after they issued their Articles on the Organization of the Church and Worship and demanded the right to excommunicate church members, which the council felt was too extreme.

The following year, her best-known work, A Very Useful Epistle, was published as an open letter in response to the council's treatment of Calvin and Farel. It was addressed to Marguerite of Navarre (l. 1492-1549), who was leading Reformation efforts in France, and who had an established relationship with Dentière. Marguerite had written Dentière asking why Calvin and Farel had been expelled from Geneva, and Dentière took the opportunity in reply of chastising the city council and advocating for a greater role for women in the Reformation movement.

Protestant works were bestsellers at this time, and the Genevan printer Jean Gerard published 1,500 copies of the letter as a booklet, expecting a handsome return. He sent Froment 450 copies to circulate while he waited for the work to catch on to sell the rest. The Genevan city council, however, denounced the letter, seized the remaining booklets from Gerard's shop, and arrested him. This work, like her earlier one, was at first attributed to Froment but, this time, Dentière had signed it with her initials. Froment was called before the city council for his inability to control his wife, was censured, and sent home. Gerard was fined and released, and the council then outlawed any publication they had not personally approved and banned any works by women in Geneva.

Dentière & Calvin

Dentière's letter failed to move the council, primarily because she characterized them as "mute dogs" who could not compare with the brilliance of Calvin and Farel and because she was a woman presuming to instruct men. The booklets taken from Gerard's shop were destroyed, but the ones sent to Froment seem to have continued circulating. The council called Calvin back to Geneva from Strasbourg in 1541 because church attendance was down, and the Reformation's momentum had slowed. Calvin only returned because he was promised it would only be for six months, but he wound up staying for the rest of his life.

When he came back, he found Dentière preaching on street corners which furthered his disdain for her as evidenced in a later account he wrote to Farel:

Froment's wife came here recently; in all the inns, at almost all the street corners, she began to harangue against long garments. When she knew that it had gotten back to me, she excused herself, laughing, and said that either we were dressed indecently, with great offense to the church, or that you taught in error when you said that false prophets could be recognized by their long garments…feeling pressured, she complained about our tyranny, that it was no longer permitted for just anyone to chatter on about anything at all. I treated the woman as I should have. (Stjerna, 143-144)

Calvin's reference to "long garments" has to do with an earlier sermon by Farel on the apparel of Catholic priests in their frocks which Dentière seems to have taken as an opportunity to mock the Protestant Reformers, who wore long coats, and who had chosen to ignore her demands for an equal voice for women in the movement. His line about her complaining "about our tyranny" is a direct reference to the refusal of the patriarchy of the Reformation to make room for women, even though women like Dentière had helped advance the cause of reform in Geneva. There is no record of Calvin ever thanking Dentière for her defense of him in 1539 and, after his return, no evidence he had very much to do with her or Froment for the next 14 years save for this one account.

In 1555, Calvin asked Dentière to write a preface to his work A Sermon on Female Apparel (also given as A Sermon on the Adorning of Women) and, for some reason, modern-day scholars sometimes interpret this to mean the two reconciled and Calvin was actually interested in what Dentière had to say. It is far more likely, especially considering the above account related to apparel, that Calvin asked Dentière for the preface in the hope she would 'learn her place', especially since Calvin's sermon drew on the biblical passage of I Timothy 2:12, which makes clear that women are not to have authority over men or presume to teach them. The preface to Calvin's sermon is the last known written work by Dentière.

Conclusion

The last years of Dentière's life are just as unclear as her youth. Froment is thought to have remarried after her death in 1561, but some scholars have suggested he separated from her before that. Froment had been replaced as a reformer first by Pierre Viret, then by Calvin – which he seems to have accepted – but Farel's letters suggest he became a subject of ridicule once his wife became a better-known preacher and writer than he had been. He preserved her works until he died, but what happened to them then, or how they survived to the modern era, is unknown.

The Reformation at first welcomed and encouraged women like Marie Dentière to speak out but, as the movement became formalized, this was only tolerated before it was suppressed. Scholar Thomas Head notes:

The right of Dentière and women like her to preach, to write, and to interpret Scripture, exercised during the period of reform struggle itself, was sharply curtailed as the Reformation consolidated its power. (Wilson, 266)

The men of the Reformation steadily gained prominence as historians focused on their contributions, while those of the many women who also fought for reform were sidelined and then forgotten until the women's movements of the 19th century began bringing them to light. Dentière's inclusion on the Reformation Wall monument in 2002 is a long-overdue acknowledgment of her efforts, even though it came over 400 years after her death, and today, women's contributions to the Protestant Reformation, as well as their reactions against it, are finally receiving the attention they have deserved.