A Very Useful Epistle (Epistre tres utile, 1539) is an open letter by the female reformer Marie Dentière (l. c. 1495-1561) to Marguerite of Navarre (l. 1492-1549) advocating for a greater role for women in the work of the Protestant Reformation. The letter was suppressed by the city council of Geneva, and Dentière's arguments were ignored by male reformers.

The full title of the work, as translated into English, is A Most Beneficial Letter, Prepared and Written down by a Christian Woman of Tournai, and Sent to the Queen of Navarre, Sister of the King of France, Against the Turks, the Jews, the Infidels, the False Christians, the Anabaptists and the Lutherans but is usually shortened to A Very Useful Epistle or A Very Useful Letter. Its supposed purpose was to encourage Marguerite of Navarre in furthering the work of the Reformation in France, but as it was published as a booklet in Geneva, it was actually intended to influence the reformers there, as well as the city council, in allowing women to study, write on and preach scripture.

Women were encouraged to read the Bible under the direction of men, but in accordance with biblical passages such as I Timothy 2:12, they were not allowed to preach or presume to have authority over men. Dentière, like the proto-feminist writer Christine de Pizan (l. 1364 to c. 1430), rejected this view, claiming women were just as able as men to interpret scripture and teach others. Whether Dentière ever read de Pizan is unknown, but many of her arguments echo de Pizan's own in The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), which also argued for women's equality.

Like de Pizan's book, Dentière's open letter failed to move the patriarchy. The work was suppressed, Dentière and her husband Antoine Froment (l. 1508-1581) fell out of favor with the reformers Guillaume Farel (William Farel, l. 1489-1565) and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), and the city council of Geneva prohibited the publication of any other works by women for the rest of the century and placed a ban on any they had not previously approved.

Background

Marie Dentière was an abbess at a nunnery in Tournai (in modern-day Belgium) when she read the works of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546), took a sum of money from the nunnery's treasury (allegedly "about five hundred ducats"), and fled to Strasbourg. She married a Reformed priest, Simon Robert, and they had five children before he died in 1533 and she married Froment. The couple moved with her children to a suburb of Geneva, where Froment became involved with Calvin and Farel between 1536 and 1538 before the latter were asked to leave the city when they would not comply with the demands of the city council.

Dentière's letter was written in 1539 in response to the expulsion of Calvin and Farel. She seems to have had an actual correspondence with Marguerite of Navarre, famous for her advocacy of the Reformation in France, but this letter appears to have actually been directed to the Genevan city council, condemning them for their treatment of Calvin and Farel, and making a case for the equal opportunity of women as preachers.

The Text

The text below omits the last part of the letter (owing to considerations of space) in which Dentière attacks the city council as "mute dogs, each gnawing a bone" while "true pastors and ministers of Jesus are persecuted, banished, and exiled" (Wilson, 280). She also strongly urges Marguerite to drive the Catholic clergy from France, characterizing them as "asses, wolves, and impudent hypocritical libertines among the sheep" who "seduce the poor people by their false doctrine and lying conversation" (Wilson, 279). The letter ends by touching on her major point that women be granted the same opportunities as men in advancing the cause of the Reformation and "the edification of all."

The following text is taken from A Reformation Reader: Primary Texts with Introductions edited by Denis R. Janz cross-referenced with Women Writers of the Renaissance and Reformation edited by Katharina M. Wilson. The "Faustus" mentioned toward the end of the text refers to the poet and scholar Publius Faustus Andrelinus (l. 1462-1518), one of the most popular writers of his day, who advanced the concept of women as weak and more prone to sin than men.

To the Very Christian Princess Marguerite of France, Queen of Navarre, Duchess of Alencon and of Berry: M.D. Wishes salvation and Increase of Grace through Jesus Christ.

Everyone, my very honored lady, especially the true lovers of truth, desire to know and hear how they ought to live in these most dangerous times; so, too, we women ought to know how to flee and avoid all errors, heresies, and false doctrines, just as much those of the false Christians, Turks, and Infidels, as those of others suspect in doctrine, as has already been shown in your writing. Although many good and faithful servants of God were inspired, in times past, to write down, preach, and announce the law of God, the coming of his Son Jesus Christ, his works, death, and resurrection, nevertheless they were rejected and reproved, principally by the wise men of the people. And not only were these people rejected, but also God's own Son, Jesus Christ, the just. Therefore, it should not amaze you if, in our time, we see similar things happen to those to whom God has given the grace of wishing to write down, speak, preach, and announce the same things that Jesus and his Apostles said and preached. We see that the whole world is full of malediction, and its inhabitants troubled, because they see the great tumults, debates, dissension, and divisions of one against the other, greater than have ever happened on earth: gross envy quarrel, rancor, malevolence, greed, wantonness, theft, pillage, drawing of blood, murder, tumult, rape, fire, poisoning, war, kingdom against kingdom, nation against nation. In short, every abomination reigns. Father against son, and son against father, mother against daughter, and daughter against mother, each wishing to sell the other: the mother to deliver her own daughter up to every misfortune.

So surely there are few, in terms of the people who are on the earth, who truly seek how they ought to live, given that such things happen among those who call themselves Christians. And one does not venture to say a word about those people, for one wishes that this thing be done, the other that; the one lives well (or so he says), the other badly; the one is wise, the other foolish; the one has knowledge, the other knows nothing; the one holds this thing dear, the other that. In short, there is nothing but division. Either one of the other must necessarily live badly. For there is only one God, one faith, one law, and one baptism.

Yet still, my very honored lady, I have wished to write you, not in order to teach you yourself, but in order that you may take care with the king your brother, to heal all these divisions, which reign in those places, towns, and peoples over which God has commissioned him to reign and govern, and also to take care for your lands, which God has given you, for the purpose of watching over and giving order. For we ought not, any more than men, hide and bury withing the earth that which God has given you and revealed to us women. Although we are not permitted to preach in assemblies and public churches, nevertheless, we are not prohibited from writing and advising one another, in all charity. I have wished to write this letter not only for you, my lady, but also to give courage to other women held in captivity, so that they will no longer fear being exiled, like me, from their countries, parents, and friends for the Word of God. And principally for those poor little women who desire to know which road, which path they ought to follow. And henceforth they will not themselves be so tormented and afflicted, but now rejoice, consoled and moved to follow the truth, which is the gospel of Jesus Christ. Even to the present day this has been so hidden that one would not dare say a word and it seemed that women ought not read anything or listen to the Holy Scripture. This is my principal cause, my lady, that which has moved me to write to you, hoping in God, that henceforth women will no longer be scorned as in the past. For day to day God changes the hearts of his own people for the good. I pray that this will shortly be so through all the world. Amen.

Not only do we wish to accuse any defamers and adversaries of the truth of very great audacity and temerity, but also any of the faithful who say that women are very impudent in interpreting Scripture for one another. To them, one is lawfully able to respond that all those who are described and named in the Holy Scripture are not to be judged to temerarious. Note that many women are named and praised in the Holy Scripture, not only for their good morals, deeds, bearing, and example, but for their faith and doctrine, like Sarah and Rebecca, and principally among all the others of the Old Testament, the mother of Moses, who, not-withstanding the edict of the king, protected her son from death and caused him to be reared in the house of the Pharaoh, as is fully described in Exodus 2. Deborah, who judged the people of Israel in the time of the Judges, is not to be scorned. I ask, would it be necessary to condemn Ruth, given the fact that she is of the feminine sex, because of the story that is written about her in her book? I do not think so; she is rightly numbered in the genealogy of Jesus Christ. The queen of Sheba had such wisdom that she is not only named in the Old Testament, but Jesus also named her among other sages.

If it is a question of speaking of the graces which have been given to women, what greater grace was given to any creature on earth than that given to the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus, to have borne the Son of God? She did not have less than Elizabeth, mother of John the Baptist, who had a son miraculously, as she was sterile. What preacheress has done more than the Samaritan woman, who was not ashamed to preach Jesus and his word, confessing it openly before all the world, as soon as she heard from Jesus that one must adore God in spirit and in truth? Or is anyone other than Mary Magdalene, from whom Jesus had driven seven devils, able to boast of having had the first revelation of the great mystery of Jesus' resurrection? And were not the other women, to whom, instead of to men, his resurrection was announced by his angel, commanded to speak, preach, and declare it to others? Just as much as there is imperfection in all women, nevertheless, the men are not exempt from it.

Why then is it necessary to gossip about women? Seeing that it was not a woman who sold and betrayed Jesus, but a man, named Judas. Who are they, I ask you, who have invented and contrived the ceremonies, heresies, and false doctrines on the earth, if not the men? And the poor women have been seduced by them. Never has a woman been found to be a false prophet, just fooled by them. Nevertheless, I do not wish to excuse by this the overly great malice of some women, which outstrips the bounds of measure. But there is no longer reason to make of that malice a general rule, without exception, as some do daily, particularly Faustus, that scoffer, in his Bucolics. Seeing that work, surely, I am unable to fall silent, given that it is more recommended and used by men than the gospel of Jesus, which is defended by us, and given that this fable teller is in good repute in the schools. If God has given graces to some good women, revealing to them something holy and good through his Holy Scripture, should they, for the sake of the defamers of the truth, refrain from writing down, speaking, or declaring it to each other? Ah! It would be too impudent to hide the talent which God has given us, we who ought to have the grace to persevere to the end. Amen!

Conclusion

Dentière had published an earlier work, The War and Deliverance of the City of Geneva (1536), anonymously, but she signed her name (her initials) to A Very Useful Epistle. Printers at this time were publishing Protestant works as quickly as they could because they sold well, and the printer Jean Gerard published 1,500 copies of the letter in booklet form. Gerard sent Froment 450 of these copies, which began to circulate, drawing the attention of the city council, who seized the rest of the booklets, jailed Gerard, and later fined and released him. Froment was called before the council to give an account of his wife's behavior, and this increased the tensions already present in his relationship with Farel and Calvin, who distanced themselves from him and his wife.

As noted, the city council outlawed any publication that did not receive their prior approval and banned any works by women. Her arguments were not considered heretical, only misguided, and her husband and Gerard seem to have been held more to blame than Dentière herself for allowing a woman such license as a public voice. Scholar Thomas Head comments:

Marie Dentière fought not only for the success of the evangelical reform in her adopted city, but also for the place of women in that movement. One of the chief attractions that the evangelical reform held for the marginal people of sixteenth-century French society was the message of universal access to religious truth. Groups who had long been the recipients of authoritative teaching rallied to the promise of the ability to test the clerical interpretation of Scripture against what they read in the vernacular. Dentière clearly states the aspirations of women to preach and interpret that Gospel message for themselves…[but] the right of Dentière and women like her to preach, to write, and to interpret Scripture, exercised during the period of reform struggle itself, was sharply curtailed as the Reformation consolidated its power. (Wilson, 266)

Dentière continued to preach openly on street corners in Geneva after the suppression of A Very Useful Epistle, even after she was censured by Calvin once he returned to the city in 1541. He later asked her to write a preface to his work A Sermon on Female Apparel (also known as A Sermon on the Adorning of Women, 1555), which some scholars interpret as a reconciliation of the two or even Calvin's eventual approval of her outspoken views.

It is far more likely, however, that Calvin asked her to write the preface to a work that relies on the I Timothy 2 passage, and others, on how women should be obedient to men and not be "impudent" and presume to speak in a man's presence in the hope that she would 'learn her place' in accordance with the biblical passages prohibiting women's participation in public affairs, especially in teaching men. In asking her to write a preface to such a work, Calvin effectively neutralized her as a theologian and preacher.

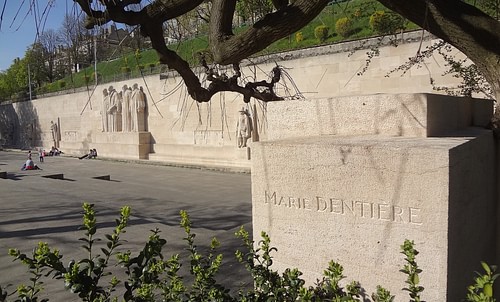

Dentière died in 1561 of natural causes, and her writings, including A Very Useful Epistle, seem to have been preserved by Froment, who dropped out of the Reformation movement afterwards and lived as a notary, periodically involved in scandals, until his death. How Dentière's writings were preserved afterwards is unclear. Her works were only rediscovered in the 19th century, and her efforts were later recognized through her inclusion on the Reformation Wall monument in Geneva. Today her open letter is frequently anthologized as an example of women's contributions to the Reformation, even though, in her time, her work was largely unappreciated, ignored, and suppressed.