The Queen of Sheba is the monarch mentioned in the Bible and then in later works who travels to Jerusalem to experience the wisdom of King Solomon (c. 965-931 BCE) of Israel first-hand. The queen is first mentioned in I Kings 10:1-13 and in II Chronicles 9:1-12 in the Bible, then in the later Aramaic Targum Sheni, then the Quran, and finally the Ethiopian work known as the Kebra Negast; later writings featuring the queen, all religious in nature, come basically from the story as first told in the Bible. There is no archaeological evidence, inscription, or statuary supporting her existence outside of these texts.

The region of Sheba in the Bible has been identified as the Kingdom of Saba (also sometimes referred to as Sheba) in southern Arabia but also with Ethiopia in East Africa. In the biblical tale, the queen brings Solomon lavish gifts and praises his wisdom and kingdom before returning to her country. Precisely where she returned to, however, is still debated as the historian Flavius Josephus (37-100 CE) famously identified her as a queen of Ethiopia and Egypt but the probable (and most commonly accepted) dates for Solomon argue in favor of a monarch from southern Arabia; even though no such monarch is listed as reigning at that time.

Ethiopia or Arabia

The debate concerning whether the queen came from Ethiopia or Arabia has been going on for centuries and will no doubt continue, even though there is no hard evidence said queen even existed. Those who argue for an Ethiopian queen claim that she reigned over the Kingdom of Axum; but Axum did not exist during the reign of Solomon nor even when the Book of Kings was composed (c. 7th/6th century BCE). Axum only existed as a political entity c. 100 - c. 950 CE. It supplanted or evolved from an earlier kingdom known as D'mt which was influenced by the Sabean culture of southern Arabia.

D'mt flourished between the 10th and 5th centuries BCE from its capital at Yeha but little else is known about the culture. Sabean influence is evident in the temple to the moon-god Almaqah, the most powerful Sabean deity, which still stands. Scholars are divided on how much the Sabeans influenced the culture of D'mt but the existence of the temple and linguistic similarities indicate a significant Sabean presence in D'mt.

This should not be surprising since Saba was a growing power c. 950 BCE and the wealthiest kingdom in southern Arabia c. 8th century BCE through 275 CE when it fell to the invading Himyarites. Whether D'mt was originally a Sabean colony is disputed, and the claim has largely been discredited but the proximity of the two kingdoms and obvious Sabean presence in D'mt suggest a close interaction. Saba was the trading hub in southern Arabia for the Incense Routes, and it would certainly make sense for them to have established friendly relations, if not a colony, just across the Red Sea.

It is possible, then, that the Queen of Sheba was a Sabean ruler of D'mt and that her legend then became associated with Ethiopia by the time Flavius Josephus was writing. It is more probable, however, that the association of Saba with D'mt led later historians, including Josephus, to claim she journeyed from Ethiopia when she actually came from Arabia. There is also, of course, the probability that she never journeyed from anywhere to anywhere because she never existed but the persistence of her legend argues for an actual historical figure.

The Queen in the Bible

The Books of I Kings and II Chronicles relates the story of the queen's visit, and it is upon these works (or whatever sources the author of Kings worked from) that later versions of the story are based. According to the biblical tale, once Solomon became king he asked his god for wisdom in ruling his people (I Kings 3:6-9). God was pleased with this request and granted it but also added riches and honor to the king's name which made Solomon famous far beyond his borders.

The queen of Sheba heard of Solomon's great wisdom and the glory of his kingdom and doubted the reports; she, therefore, traveled to Jerusalem to experience it for herself. The Bible only states that the monarch is “the queen of Sheba” (I Kings 10:1) but never specifies where “Sheba” is. Her purpose in coming to see the king was “to prove him with hard questions” (I Kings 10:1) and, once he had answered them and shown her his wisdom, she presented Solomon with lavish gifts:

And she gave the king a hundred and twenty talents of gold, and of spices very great store, and precious stones: there came no more such abundance of spices as these which the queen of Sheba gave to Solomon. (I Kings 10:10)

The 120 gold talents would amount to approximately $3,600,000.00 in the present day and this kind of disposable wealth would certainly be in keeping with the affluence of the Sabean monarchy though not necessarily during Solomon's reign. The mention of the great amount of gold and, especially, the “abundance of spices” certainly suggest Saba, whose main source of wealth was the spice trade, but evidence suggests Saba was most prosperous only from the 8th century BCE onward.

After giving Solomon these gifts, the queen then receives from him “all her desire, whatsoever she asked, besides that which Solomon gave her of his royal bounty” and then returns to her country with her servants (I Kings 10:13). Following her departure, the narrative details what Solomon did with her gifts and with the almug trees and gold which Hiram of Tyre had brought him from the land of O'phir (I Kings 10:11-12, 14-26). Nothing further is mentioned of the queen in I Kings and her appearance in II Chronicles 9:1-12 follows this same narrative.

The Targum Sheni Version

By the time the story is repeated in the Targum Sheni, however, it has expanded with significantly more detail. The Targum Sheni is an Aramaic translation of the biblical Book of Esther with commentary but includes the story of the Queen of Sheba as one of its ancillary tales. This version takes the biblical tale of the queen's visit and embellishes it with touches of mythology which most likely had grown up around the figure of Solomon. Solomon's wisdom, according to the Bible, enabled him to understand the language of the trees, animals, and birds (I Kings 4:33). The Targum Sheni picks up on this thread and begins its story with Solomon inviting all the birds and animals of his kingdom to a great feast.

The creatures all gratefully accept the invitation except for the woodcock who declines, pointing out that Solomon is not as great a monarch as the Queen of Sheba and so does not deserve this level of respect. Solomon then invites the queen to his palace to do homage to him and prove the woodcock wrong and, in order to make a greater impression on her, has one of the spirits under his command transport the queen's throne to him. When the queen arrives she is suitably impressed, walking across a floor of glass which seems water, but still tests Solomon by asking him difficult riddles which, through his wisdom, he is able to answer; the queen then pays him homage, and presumably, the woodcock is satisfied.

The Targum Sheni comes from the genre of rabbinic literature known as the midrash: commentaries and interpretation of scripture. The work has been dated to between the 4th-11th centuries CE with different scholars arguing for an earlier or later date based on textual clues. This debate, like the one surrounding the queen's country of origin, continues but it seems likely that the Quran borrows the story from the Targum Sheni since the Islamic work regularly makes use of other older material. To cite only one such example, the Greek story of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus appears in a revised form in Sura 18. Like the tale of the Seven Sleepers, the story of the queen of Sheba changes in the Quran to fit the overall vision of the work.

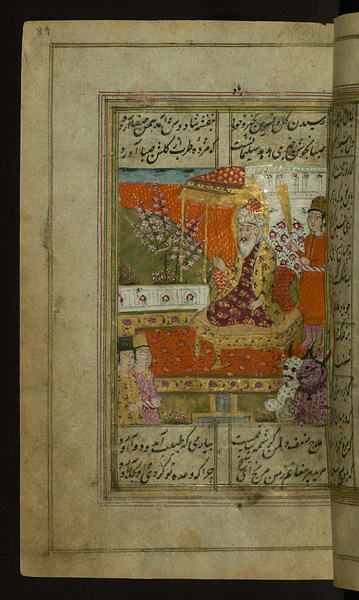

The Queen in the Quran

In the Quran, the queen is known as Bilqis and rules over the mighty kingdom of Sheba. In this version of the story, as in the Bible, Solomon (given as Sulayman) is given the gift of the speech of birds, animals, and the spiritual entities known as jinn (genies). He assembles his hosts one day to inspect them but does not find the hoopoe bird among the company. Solomon says:

How is it with me that I do not see the hoopoe? Or is he among the absent? Assuredly I will chastise him with a terrible chastisement, or I will slaughter him, unless he bring me a clear authority [provide a good excuse]. (Sura 27:20)

The hoopoe bird appears and tells Solomon that he has been flying far and came to the land of Sheba where, he says, “I found a woman ruling over them and she has been given of everything and she possesses a mighty throne” (Sura 27:20). The bird then goes on to say how the people of Sheba worship the sun, not the god of Solomon, Allah, and how Satan has led them astray so that, although they have a great kingdom, they “are not guided, so that they prostrate not themselves to God” (Sura 27:25). Solomon forgives the bird his earlier absence and sends him with a letter to the queen, inviting her to visit his kingdom.

When the queen receives the letter, she calls a council and reads aloud how Solomon wishes her to come to him in submission to his god. She asks the council for advice, and they tell her they are ready to fight for her but the decision must finally be hers. She decides to send Solomon a gift through a messenger, but the king rejects it and tells the messenger that, unless the queen complies, he will “come against them with hosts they have not power to resist and we shall expel them from there, abased and utterly humbled” (Sura 27:35). After the messenger leaves, Solomon remembers what the hoopoe bird said about the queen's throne and asks his council-members who among them can bring him the royal seat before the queen arrives. A jinn assures him it can be done and brings him the throne.

Once the throne is installed in a pavilion made of crystal, Solomon disguises it. When the queen arrives, he asks her if it is her throne and she replies that it seems to be the same. She is then told to enter the pavilion where she bares her legs before stepping onto the floor because it is so clear she thinks it is water. The wonder of the crystal pavilion and the appearance of her own throne there overwhelms the queen, and she says, “My lord, indeed I have wronged myself and I surrender with Solomon to God, the Lord of all Being” (Sura 27:45). Once the queen has submitted to Solomon's god the narrative in the Quran ends but Islamic tradition and legend suggests that she married Solomon.

The Kebra Negast Version

In the Kebra Negast (“The Glory of Kings”) of Ethiopia this story is retold but developed further. Here, the queen's name is Makeda, ruler of Ethiopia, who is told of the wonders of Jerusalem under Solomon's reign by a merchant named Tamrin. Tamrin has been part of an expedition to Jerusalem supplying material from Ethiopia for the construction of Solomon's temple. He tells his queen that Solomon is the wisest man in the world and that Jerusalem is the most magnificent city he has ever seen.

Intrigued, Makeda decides to go visit Solomon. She gives him gifts and is given gifts in return and the two spend hours in conversation. Toward the end of their time together, Makeda accepts Solomon's god and converts to Judaism. Solomon commands a great feast to celebrate Makeda's visit before her departure, and she spends the night in the palace. Solomon swears an oath that he will not touch her as long as she does not steal from him.

Makeda agrees but, in the night, becomes thirsty and finds a bowl of water which Solomon has placed in the center of the room. She is drinking the water when Solomon appears and reminds her that she swore she would not steal and yet here she is drinking his water without permission. Makeda tells him he can sleep with her since she has broken her oath.

Before she leaves Jerusalem, Solomon gives her his ring to remember him by and, on her journey home, she gives birth to a son whom she names Menilek (“son of the wise man”). When Menilek grows up and asks who his father is, Makeda gives him Solomon's ring and tells him to go find his father.

Menilek is welcomed by Solomon and stays in Jerusalem for some years studying the Torah. In time, however, he must leave and Solomon decrees that the first-born sons of his nobles will accompany Menilek back home (possibly because the nobles had suggested Menilek should leave). Before the group departs, one of the sons of the nobles steals the ark of the covenant from the temple and replaces it with a duplicate; as the caravan leaves Jerusalem, the ark goes with them.

The theft of the ark is discovered soon after, and Solomon orders his troops to pursue but they cannot catch up. Menilek, meanwhile, has discovered the theft and wants to return the ark but is persuaded that this is the will of God and the ark is supposed to travel to Ethiopia. In a dream, Solomon is also told that it is God's will the ark was taken and so calls off his pursuit and tells his priests and nobles to cover up the theft and pretend the ark in the temple is the real one. Menilek returns to his mother in Ethiopia with the ark which is enshrined in a temple and, according to legend, remains there to the present day.

Conclusion

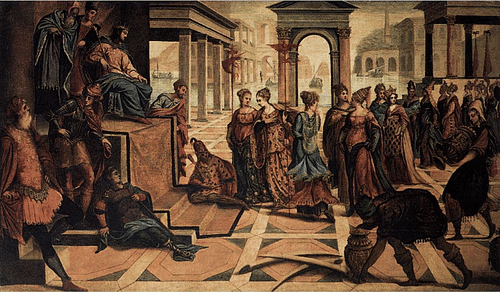

There are other later sources which also feature the mysterious queen and argue for or against her historicity. The Christian canticles of the Middle Ages, drawing on the New Testament references to a “Queen of the South” as the Queen of Sheba (Matthew 12:42 and Luke 11:31), represented her as a mystical figure. Christian art of the Middle Ages and Renaissance often chose the queen as a subject depicted either alone or in the company of Solomon.

The Talmud claims that there never was such a queen and that the reference to a queen in I Kings is meant to be understood figuratively: the “queen of Sheba” should be understood to mean the “kingdom of Sheba”, not an actual person (Bava Batra 15b). Other traditions seem to indicate there was such a queen but who she was and where she came from remains a mystery.

There is no reason to question the claim that a diplomatic mission may have been sent from Saba to Jerusalem during the reign of Solomon and that the emissary would have been a woman. The queen could have been the daughter of one of the Sabean kings or perhaps ruled on her own after the death of her husband.

There is, as noted, no record of a queen of Saba but neither is there any indication of a queen of Sheba named Makeda in Ethiopia or any record of a queen name Bilqis outside of the Quran. Historically, the Queen of Sheba remains a mystery but her legend has endured for millennia and she continues to inspire literature and art in her honor in the present day.