The African kingdom of Axum (also Aksum) was located on the northern edge of the highland zone of the Red Sea coast, just above the horn of Africa. It was founded in the 1st century CE, flourished from the 3rd to 6th century CE, and then survived as a much smaller political entity into the 8th century CE.

The territory Axum once controlled is today occupied by the states of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Somaliland. Prospering thanks to agriculture, cattle herding, and control over trade routes which saw gold and ivory exchanged for foreign luxury goods, the kingdom and its capital of Axum built lasting stone monuments and achieved a number of firsts. It was the first sub-Saharan African state to mint its own coinage and, around 350 CE, the first to officially adopt Christianity. Axum even created its own script, Ge'ez, which is still in use in Ethiopia today. The kingdom went into decline from the 7th century CE due to increased competition from Muslim Arab traders and the rise of rival local peoples such as the Bedja. Surviving as a much smaller territory to the south, the remnants of the once great kingdom of Axum would eventually rise again and form the great kingdom of Abyssinia in the 13th century CE.

Name & Foundation

The name Axum, or Akshum as it is sometimes referred to, may derive from a combination of two words from local languages - the Agew word for water and the Ge'ez word for official, shum. The water reference is probably due to the presence of large ancient rock cisterns in the area of the capital at Axum.

The region had certainly been occupied by agrarian communities similar in culture to those in southern Arabia since the Stone Age, but the ancient kingdom of Axum began to prosper from the 1st century CE thanks to its rich agricultural lands, dependable summer monsoon rains, and control of regional trade. This trade network included links with Egypt to the north and, to the east, along the East African coast and southern Arabia. Wheat, barley, millet, and teff (a high-yield grain) had been grown with success in the region at least as early as the 1st millennium BCE while cattle herding dates back to the 2nd millennium BCE, an endeavour aided by the vast grassland savannah of the Ethiopian plateau. Goats and sheep were also herded and an added advantage for everyone was the absence of the tropical parasitic diseases that have blighted other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Wealth acquired through trade and military might was added to this prosperous agricultural base and so, in the late 1st century CE, a single king replaced a confederation of chiefdoms and forged a united kingdom that would dominate the Ethiopian highlands for the next six centuries. The kingdom of Axum, one of the greatest in the world at that time, was born.

Expansion

The kingdom of Axum really started to take off around 350 CE. Axum had already established some form of dominance over Yemen (then called Himyar) in southern Arabia as well as Somalia in the southeast and several smaller tribes to the southwest. Subjugated tribes, although left semi-autonomous, had to pay tribute, typically in the form of hundreds of heads of cattle (as indicated by Axumite inscriptions). This perhaps gave some slight justification to the Axum rulers now calling themselves by the rather grand title Negusa Negast or 'king of kings.' Details of the Axum government and how this absolute monarch controlled conquered tribes over the centuries are lacking but the title 'king of kings' would suggest conquered rulers were permitted to continue to reign over their own peoples.

In the mid-4th century CE, Nubia (formerly known as Kush and located in modern Sudan), with its capital at Meroe, attacked Axum from the north (or vice-versa), perhaps because of a dispute over control of the region's ivory trade. The Axum king Ezana I (r. c. 303-350 CE) responded with a large force, sacking Meroe. Once mighty Nubia, already in serious decline and weakened by overpopulation, overgrazing and deforestation, was soon toppled and broke up into three separate states: Faras, Dongola, and Soba. This collapse left the way clear for Axum to dominate the region.

Another period of great Axum expansion came during the reign of Kaleb I in the first quarter of the 6th century CE. The kingdom came to occupy a territory about 300 kilometres in length and 160 kilometres across; not so large perhaps, but its control of trade goods was the key, not geography. Rulers were keen, too, to indulge in a spot of imperialism across the Red Sea in Yemen in an effort to completely control the many trading vessels that sailed down the Straits of Bab-al-Mandeb, one of the busiest sea stretches in the ancient world. Raids had been made in Yemen in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, but it was the 6th century CE which saw a major escalation in Axum ambitions. The king of Yemen, Yusuf As'ar Yathar, had been persecuting Christians since 523 CE, and Kaleb, who himself then ruled over a Christian state, responded by sending a force to Yemen in c. 525 CE. This invasion was supported by the Byzantine Empire with whom Axum had long-established diplomatic ties (whether the support was merely diplomatic or material is not agreed upon by scholars). Victorious, the Axum king was able to leave a substantial garrison and install a viceroy which ruled the region until the Sassanids arrived in 570 CE.

Axum the Capital

The ancient city of Axum (sometimes called Axumis) is located at an altitude of over 2,000 metres (6800 ft) in the north of the Ethiopian highlands (in the modern province of Tigray), close to the River Tekeze, a tributary of the Nile. The city, occupied from the 1st century CE, was both the capital of a trading empire and a ceremonial centre which included many stone monuments. Some such monuments are very similar to Egyptian obelisks, although curiously, the granite stone is sometimes worked to resemble architectural features of dry-stone and timber Axumite buildings. Many of these stelae are around 24 metres (78 ft) in height, although one fallen and now broken example is 33 metres (108 ft) in total length and 520 tonnes in weight, making it the largest monolith ever to have been transported anywhere in antiquity. The stelae were likely transported on log rollers from a quarry 4.8 km (3 miles) away. Almost all were used as tomb markers and many have a carved stone throne next to them, often covered in inscriptions.

Other remains of stone structures include three palace-like buildings which once had towers - each with stone pillared basements, royal tombs with massive walls creating separate chambers, water cisterns, irrigation channels, and two- or three-story buildings used as residences by the Axum elite. Most large structures were built on a stepped granite base composed of dressed blocks, with access provided by monumental staircases, usually consisting of seven steps. Stone lion-head gargoyles often provided roof drainage.

Stone structures used clay instead of mortar, with a decorative effect achieved by alternating projecting and recessed blocks. Wood was used between stone layers for horizontal support in walls, for doorways, window frames, floors, roofs, and in ceiling corners to give extra structural support. The decoration on many of buildings at Axum and the motifs used in Axumite art in general such as the astral symbols of disc and crescent are evidence of influence from South Arabian cultures across the Red Sea (although the influence may have been in the opposite direction). The capital also had dedicated areas for craft workshops and, from the late 4th century CE, many churches.

Trade

Gold (acquired from the southern territories under the kingdom's control or from war booty) and ivory (from Africa's interior) were Axum's main exports - the Byzantines, in particular, could not get enough of both - but other goods included salt, slaves, tortoiseshell, incense (frankincense and myrrh), rhino horns, obsidian and emeralds (from Nubia). These goods went to the kingdom's seaport of Adulis (modern Zula and actually 4 km from the sea), carried to the coast by camel caravans. There they were exchanged for goods brought by Arab merchants such as Egyptian and Indian textiles, swords and other weapons, iron, glass beads, bronze lamps, and glassware. The presence of Mediterranean amphorae at Axum sites indicates that such goods as wine and olive oil were also imported. That Axum trade was booming is evidenced by the finding of the kingdom's coinage at such far-flung places as the eastern Mediterranean, India, and Sri Lanka.

Adoption of Christianity

In the mid-4th century CE, the king of Axum, Ezana I, officially adopted Christianity. Prior to that, the people of Axum had practised an indigenous polytheistic religion which was prevalent on both sides of the Red Sea with some local additions such as Mahram, god of war, upheaval, and monarchy, who was the most important Axumite god. Other notable gods included the moon deity Hawbas, Astar, the representation of the planet Venus, and the chthonic gods Beher and Meder. Such gods, as well as ancestors, had sacrifices made in their honour, especially cattle - either living animals or votive representations of them.

Traders and Egyptian missionaries had brought Christianity to the region during the early centuries of the 1st millennium CE, and the official acceptance by Aksum may have occurred because the kingdom had important trade connections to the North African provinces of the Roman Empire, which itself had adopted Christianity a couple of decades earlier. Indeed, there were many trade and diplomatic connections directly between Constantinople and Axum, and it is probable that this passage of individuals to and fro also introduced Christianity into Ethiopia. It is important to note, though, that the more ancient indigenous religious beliefs likely carried on for some time, as indicated by the careful wording of rulers' inscriptions so as not to alienate that part of the population which did not accept Christianity.

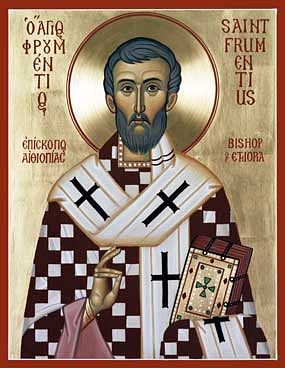

According to traditional accounts, it was Frumentius, a 4th-century CE shipwrecked traveller from Tyre, who introduced Christianity to the kingdom. Frumentius gained employment as a teacher to the royal children, and then he became treasurer and advisor to the king, probably Ella Amida. When Ella Amida was succeeded by his son Ezana I, whom Frumentius had even greater sway over given that he had been his childhood tutor, the king was persuaded to adopt Christianity. Frumentius next travelled to Alexandria to receive an official title from the Patriarch there in order to aid his missionary work, then he returned to Axum and became the first bishop of the kingdom. The dates of exactly when all this happened are wildly different depending on one's ancient source and range from 315 to 360 CE, with the latter end of that range being the more likely according to modern scholars. Frumentius was later made a saint for his efforts in spreading the Gospel in East Africa.

The form of Christianity at Aksum was similar to that adopted in Coptic Egypt, indeed, the Patriarch of Alexandria remained a strong figurehead in the Ethiopian Church even when Islam arrived in the region from the 7th century CE. Churches were built, monasteries founded, and translations made of the Bible. The most important church was at Axum, the Church of Maryam Tsion, which, according to later Ethiopian medieval texts, housed the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark is supposed to be still there, but as nobody is ever allowed to see it, confirmation of its existence is difficult to achieve. The most important monastery in the Axum kingdom was at Debre Damo, founded by the 5th-century CE Byzantine ascetic Saint Aregawi, one of the celebrated Nine Saints who worked to spread Christianity in the region by establishing monasteries. From the 5th century CE the rural population was converted, although, even in cities, some temples to the old pagan gods would remain open well into the 6th century CE. The success of these endeavours meant that Christianity would continue to be practised in Ethiopia right into the 21st century CE.

A Cultural Mix: Writing & Coinage

The area which Axum would later occupy used an Arabian type script from the 5th century BCE called Sabaean (a Semitic language then used in Southern Arabia). Greek was also used in some inscriptions. The kingdom of Axum had its own writing system, the earliest examples of which are found on sheets of schist rock slabs which date to the 2nd century CE. This script, called Ge'ez or Ethiopic, resembles Sabaean but had gradually evolved into a quite distinct script which included characters for vowels and consonants and which was read from left to right. The Ge'ez script is still used today in modern Ethiopia.

Another example of Axum's tendency to profitably mix ideas from different cultures can be seen in the kingdom's coinage, the first sub-Saharan kingdom to have its own mint. The gold and silver coins of Axum, which appeared from the 3rd century CE onwards, have Greek inscriptions, Sabaean religious symbols, and they were minted adhering to Roman standard weights. The most common material of the thousands of Axum coins discovered is bronze. Coins and their legends are often our only information on Axum's various kings, 20 in total. A portrait of the king is usually accompanied by two ears of corn and, from the reign of Ezana I, a Christian cross. Legends include the name of the king, his title and an uplifting phrase, for example, 'Peace to the People' and 'Health and Happiness to the People.'

Art

In the arts, Axum potters produced simple red and black terracotta wares but without using a wheel. Wares are usually matt in finish, and some are coated with a red slip. Forms are simple cups, bowls, and spouted jugs. Decoration of geometric designs was achieved using incisions, painting, stamps, and added three-dimensional pieces. By far the most common decorative motif is the Christian cross. There seems not to have been either the inclination or know-how to produce the finer wares which Axum imported from Mediterranean cultures.

No large-scale statues have been discovered from the kingdom but there are stone bases. One example has indentations for feet carved into it with each foot space measuring 90 cm (35 inches) which would make the standing figure three-times life-size. An inscription on the base indicates that there once stood a large metal figure on it, probably of a divinity. The same inscription mentions other statues of gold and bronze. The stone thrones found near stelae may also have had seated metal statues on them. Small scale figurines abound and these depict nude females and animals. Unfortunately, the impressive stone chamber tombs of the kingdom were all looted in antiquity and only broken fragments of precious materials and pieces of storage chests and boxes indicate what has been lost to posterity.

Decline & Later History

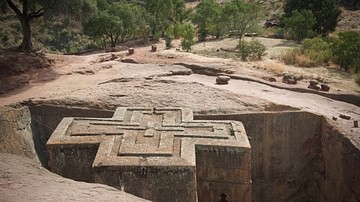

The kingdom of Axum went in decline from the late 6th century CE, perhaps due to overuse of agricultural land or the incursion of western Bedja herders who, forming themselves into small kingdoms, grabbed parts of Aksum territory for grazing their cattle and who persistently attacked Axum's camel caravans. In addition, the policy of Axum's kings to allow conquered tribal chiefs a good deal of autonomy often backfired and permitted some of them to have the means to launch rebellions. Ultimately, Axum would pay dearly for its lack of any real state administrative apparatus. Finally, there was from the early 7th century CE stiff competition for the Red Sea trade networks from Arab Muslims. The heartland of the Axum state shifted 300 km (186 miles) southwards to the cities of Lalibela and Gondar. As a consequence of the decline, by the late 8th century CE the old Axum Empire had ceased to exist.

The city of Axum fared better than its namesake kingdom and never lost its religious significance. The territory of the kingdom of Axum would eventually develop into the medieval kingdom of Abyssinia with the founding of the Solomonid dynasty c. 1270 CE, whose kings claimed direct descent from the Biblical King Solomon and Queen of Sheba.