A cyclops (meaning 'circle-eyed') is a one-eyed giant first appearing in the mythology of ancient Greece. The Greeks believed that there was an entire race of cyclopes who lived in a faraway land without law and order. Homer, in his Iliad, describes the Cyclopes as pastoral but savage, typical of the strange creatures the Greeks created to represent foreign societies not regarded as civilised as themselves.

The Cyclopes are not without talents, though, and are credited with manufacturing the thunderbolts which Zeus used as a terrible throwing weapon and as the builders of gigantic fortification walls such as those still seen at Mycenaean sites today. The most famous cyclops is Polyphemus, who captured the Greek hero Odysseus and his men only for them to escape by blinding the poor giant. Cyclopes, and particularly the Odysseus story, were popular and enduring subjects in all forms of Greek and Roman art.

Origins & Name

Hesiod (c. 700 BCE), writing in his Theogony, tells us that the Cyclopes were the children of Earth (Gaia) and Sky (Ouranos/Uranus), making them the generation before the Olympian gods. The Cyclopes were thought to dwell in a faraway land of unknown location or name where there were no laws. There these giant creatures lived a simple pastoral existence herding sheep and goats and living in caves.

Hesiod names three cyclopes as Brontes (Thunder), Steropes (Lightning), and Arges (Bright). This group would go on to father more of their kind although the trio was later killed by Apollo in revenge for Zeus' murder of his son Asclepius, the demigod and master of medicine. The ghosts of the three were said to haunt the Mount Etna volcano on Sicily. Indeed, many local Greek traditions associated cyclopes with volcanoes, perhaps because their craters were reminiscent of the cyclopes' one eye, often described in ancient literature as 'burning.' Hesiod also makes the Cyclopes master craftsmen and assistants to the god Hephaistos, himself the ultimate blacksmith and ingenious inventor (and sometimes-resident within Mt. Etna).

Hesiod goes on to explain their name, too:

These were like the gods in other regards, but only one eye was set in the middle of their foreheads; and they were called Cyclopes (Circle-eyed) by name, since a single circle-shaped eye was set in their foreheads. Strength and force and contrivances were in their works.

(Theogony, 142-147)

The famed historian and expert on Greek mythology Robert Graves makes the following connection between the Cyclopes, fire and metallurgy:

The Cyclopes seem to have been a guild of Early Helladic bronzesmiths. Cyclops means 'ring-eyed', and they are likely to have been tattooed with concentric rings on the forehead, in honour of the sun, the source of their furnace fires…The Cyclopes were one-eyed also in the sense that smiths often shade one eye with a patch against flying sparks.

(3b 2)

Hesiod describes the Cyclopes as having 'very violent hearts' (139-140), making them typical of other fantastic creatures in Greek mythology such as the centaurs which represent lawlessness and who are subject to the chaotic forces that an absence of reason brings. Living in isolation, the Cyclopes live solitary and insular lives; they have no government, society or sense of community - deficiencies that civilised Greeks thought abominable.

Homer, in his 8th-century BCE Odyssey, like Hesiod, stresses the lack of civilization amongst the Cyclopes:

No laws, no councils for debate have they;

They live on the tips of lofty mountains,

In hollow caves; each man lays down the law

To wife and children, with no regard for neighbour.

(Bk. 9, 112-115)

This exact same passage is repeated in Plato's Laws (Bk. III, 680b). The philosopher, writing this later work in the mid-4th century BCE, has his characters discuss the virtues and faults of existing political systems as they search for the ideal form of government, and the Cyclopes are held up as one of the poorer examples of communal existence.

Perhaps not surprisingly, due to their status as lawless monstrosities rather than gods, the Cyclopes did not play very much part in Greek religion. There was one place where the one-eyed giants were worshipped, though, that was the Isthmus of Corinth, perhaps because of a connection with Poseidon, often seen as the father of the cyclops Polyphemus (see below). The Isthmian Games were held here every two years in honour of Poseidon, and there was an altar which received sacrifices for the Cyclopes.

Master Craftsmen & Builders

The Cyclopes helped the Olympian gods led by Zeus to defeat the Titans in their ten-year battle, known as the Titanomachy, for control of the universe. The Cyclopes, in gratitude for their release after Uranus had imprisoned them in Tartarus for unruly behaviour, made the thunderbolts that Zeus used as a weapon to strike down his enemies. Victims hit by Zeus' well-aimed thunderbolts included Asclepius when Zeus considered that his medical skills had become so wonderful that he was a threat to the eternal division between humanity and the gods. The Cyclopes also made the helmet of Hades which made the wearer invisible, the trident of Poseidon, and the silver bow of Artemis.

Another area of expertise the Cyclopes excelled at was building walls. Large Mycenaean fortification walls were credited to them; such was the huge size and irregular shape of the blocks used. The acropolis of Mycenae and Tiryns still have today long stretches of these 'Cyclopean walls.'

Odysseus & Polyphemus

The most famous encounter between humans and a cyclops was during the long voyage home from the Trojan War endured by the hero Odysseus. The story is recounted most famously in the Odyssey by Homer. Mid-journey at an unknown location, the hero stops at an island for supplies. Unfortunately, the island was also inhabited by the cyclops Polyphemus, the son of the nymph Thoosa and Poseidon, and the giant took a distinct fancy to the travelling Greeks. Trapping them in his cave by blocking the entrance with a huge boulder only a giant could move, he swiftly ate two as an appetizer and then later a couple more of the hapless travellers.

Seeing the gravity of the situation, Odysseus, known for his intelligence and quick wits, developed a cunning plan of escape. Tempting Polyphemus with wine until the cyclops was drunk, the hero ordered his men to turn Polyphemus' olive-wood staff into a spike, this they then hardened in a fire and then used it to blind the cyclops while he slept. Unable to see and understandably livid at his treatment, Polyphemus tried to catch the still trapped travellers by feeling his sheep as they left the cave for their grazing. Odysseus then instructed his men to tie themselves to the bellies of the sheep whilst he chose a ram for the purpose, and thus they escaped to continue their voyage. However, the cyclops, after unsuccessfully hurling a boulder to try and smash the fastly-disappearing Greek ship, cursed Odysseus, predicting the loss of his men, a wearisome voyage home, and disaster when he finally arrived there. Calling on the help of his father Poseidon, Polyphemos ensured that it would be many a storm and ten long years before Odysseus reached Ithaca.

The Cyclopes in Literature & Art

The Cyclopes are both the title and subject of a satyr play by Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE), the great writer of Greek tragedy. The plot is much like Homer's Odyssey but with the added character of the elderly satyr named Silenus, who gives additional help to Odysseus and his men as they battle wits with Polyphemus. Another traditional story of Polyphemus involves him hopelessly trying to woo the sea-nymph Galatea, a tale popular with ancient pastoral writers and an early prototype for the Beauty and the Beast fairytale. In the better-known version, Polyphemus sings a love song to Galatea but without any effect, except to surprise the nymph's actual lover Acis, who tries to swim away but is crushed and drowned after the cyclops employs his weapon of choice and throws a huge rock at him. In the lesser-known version, Polyphemus is more successful in his ambitions and he and Galatea have a son called Galas (or Galates) who became the ancestor of the Gauls.

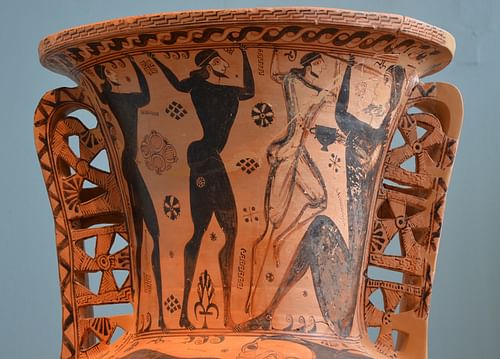

The struggle between Odysseus and Polyphemus was a popular subject for painters of Greek pottery with the blinding of the cyclops being by far the most common and enduring scene chosen. Appearing on the black-figure pottery of many different Greek city-states, the earliest known instance of this terrible deed is on the neck of a 7th-century BCE Proto-attic amphora from Eleusis. Odysseus and two men carry the spiked pole above their heads and, curiously, one figure is painted white, a colour usually reserved for women but perhaps here an attempt to pick out Odysseus as the group's leader. The vase can be seen today in the archaeological museum at Eleusis. In this and other such scenes, Polyphemus is typically seated on the floor, probably to show his collapsed drunkenness - he sometimes holds a cup or a wineskin suggestively hangs from a tree in the background - although it may also be an artistic necessity to fit the giant and men on the same horizontal plane. In some of these scenes, Polyphemus does not always have just one eye, or at least not obviously so. The blinding scene and also the escape tied to the sheep of Polyphemus appear on vases for the next two centuries, although this part of the Odyssey story ceased to be a popular subject with later red-figure pottery painters.

The Cyclopes in Roman Culture

The Cyclopes in general remained a popular subject in art well into Roman times. The Romans often depicted the giants as having a single eye in the centre of the forehead and two normal eyes which are closed, the love story between Galatea and Polyphemus being an especially popular subject. Represented in paintings, mosaics and sculpture, surviving renditions of a cyclops in the latter medium include an impressive stone head of Polyphemus from the amphitheatre of Salona (1st century CE) in Croatia and the sculptural group of Odysseus and friends blinding their foe from the villa of Tiberius at Sperlonga (also 1st century CE). The Romans, too, sometimes used a cyclops as the face of a stone mask which adorned outdoor swimming pools and functioned as a decorative fountain. Again, these often have three eyes, and an outstanding 1st-century CE example can be seen in the archaeological museum of Orange, France.