The Colossi of Memnon (also known as el-Colossat or el-Salamat) are two monumental statues representing Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. They are located west of the modern city of Luxor and face east looking toward the Nile River. The statues depict the seated king on a throne ornamented with imagery of his mother, his wife, the god Hapy, and other symbolic engravings. The figures rise 60 ft (18 meters) high and weigh 720 tons each; both carved from single blocks of sandstone.

They were constructed as guardians for Amenhotep III's mortuary complex which once stood behind them. Earthquakes, floods, and the ancient practice of using older monuments and buildings as resource material for new structures all contributed to the disappearance of the enormous complex. Little of it remains today except for the two colossal statues which once stood at its gates.

Their name comes from the Greek hero Memnon who fell at Troy. Memnon was an Ethiopian king who joined the battle on the side of the Trojans against the Greeks and was killed by the Greek champion Achilles. Memnon's courage and skill in battle, however, elevated him to the status of a hero among the Greeks. Greek tourists, seeing the impressive statues, associated them with the legend of Memnon instead of Amenhotep III and this link was also suggested by the 3rd century BCE Egyptian historian Manetho who claimed Memnon and Amenhotep III were the same person.

The Greek writers referred to the entire complex regularly as the Memnonium and the site became legendary for divination after one of the statues began making noises interpreted as oracles. From ancient times to the present the Colossi have been a popular tourist attraction and in the present day one can see graffiti inscribed on the base from visitors thousands of years ago.

Amenhotep III & the Glory of Egypt

Amenhotep III lived during the period of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-c. 1069 BCE) in which Egypt became a country of international power and wealth. His father, Thutmose IV (1400-1390 BCE), left his son a prosperous and stable empire of substantial riches which the new king used wisely. He was only twelve years old when he came to the throne and married Tiye, a girl of only eleven or twelve, who came from a prestigious family. Tiye was given the title of Great Royal Wife, an honor which even Amenhotep III's mother had not been accorded. This title reflects the great status of both Amenhotep III and Tiye as a royal couple of impressive power.

In keeping with the traditions of powerful pharaohs, Amenhotep III almost instantly embarked on grand building projects throughout Egypt. His vision was of a land so splendid and opulent that it would leave one in awe and the over 250 buildings, temples, statuaries, and stele he commissioned attest to his success in realizing this. His pleasure palace at Malkata, on the west bank of the Nile near Thebes, covered over 30,000 square meters (30 hectares) and included spacious apartments, conference rooms, audience chambers, a throne room and receiving hall, a festival hall, libraries, gardens, storerooms, kitchens, a harem, and a temple to the god Amun.

Amenhotep III commissioned so many monuments, temples, and other building projects that later Egyptologists attributed to him an extraordinarily long reign because it seemed impossible that one king could have had the resources to accomplish what he did in less than 100 years. Amenhotep III, of course, ruled for far less time but was so effective a king that he accomplished far more than most.

He was a master of diplomacy who placed other nations in his debt through lavish gifts to ensure they would be inclined to bend to his wishes. His generosity to friendly kings was well established and he enjoyed profitable relationships with the surrounding nations which filled Egypt's royal treasury. He maintained the honor of Egyptian women in refusing requests to send them as wives to foreign rulers, claiming that no daughter of Egypt had ever been sent to a foreign land and would not be sent under his reign. While other nations may not have felt at all flattered by this policy, it expressed an adherence to tradition and cultural values which won their respect.

Throughout his reign, Amenhotep III improved upon his father's very sound policies of rule and in religion he did likewise. Amenhotep III was an ardent supporter of the ancient religion of Egypt and expressed his interest lavishly in patronage of the arts and in building projects. Among the most opulent was his mortuary temple complex which included the massive figures of the Colossi of Memnon.

The Grand Mortuary Complex

Amenhotep III's mortuary complex was larger and greater in every way than anything previously built in Egypt. At the time of its construction it was more magnificent and awe-inspiring than the Temple of Karnak. It covered over 86 acres (35 hectares) and included numerous rooms, halls, porticos and plateaus which probably mirrored the vision of the Field of Reeds, the Egyptian paradise. In their time, the colossal statues of the king would have flanked a walkway, probably ornamented with statuary, leading to the complex.

There was an open sun court adjacent to the temple surrounded by three rows of columns and, on the north and south sides, statues of the king as Osiris in mummified form. This was in keeping with the tradition of kings associating themselves with Horus during their reign and with his father Osiris in death. The statues were 26 feet (8 meters) tall; those on the south side of the court wore the white crown of Upper Egypt while those on the north wore the red crown of Lower Egypt.

The statues of the king symbolized his rule over all Egypt, identified him with Osiris, and made clear the king's wealth and power. Osiris was believed to have been the first king of Egypt and the Lord and Judge of the Dead. Even though kings before and after Amenhotep III associated themselves with Osiris in their mortuary complexes, Amenhotep III made his close relationship with the god both more apparent and more impressive.

Most Egyptians would never have been allowed into the complex to see these statues, the sun court, or anything else but they would have been aware of the great figures who stood at the gates which could be seen for miles from every direction. Egyptologist Gay Robins notes that the statues' function "was to guard the entrance to the complex, to inspire awe at the king's might, and to celebrate the acheivements of the state" (130). Their ability to awe is well established by writers from ancient times to the present owing to their sheer size and the amount of effort it must have taken to create them.

The Guardians of the Gate

The statues were carved from single blocks of quartzite sandstone quarried either from the area around Memphis (near modern-day Cairo) in the north or from the region near Aswan in the south. If quarried from the north, the blocks had to be transported overland 400 miles (645 km) and, if from the south, 147 miles (238 km) as they were too heavy to move by ship on the Nile. How the stones were transported is unknown but they were most likely pushed on sleds in the same way blocks of stone were moved to the site of Giza for construction of the pyramids.

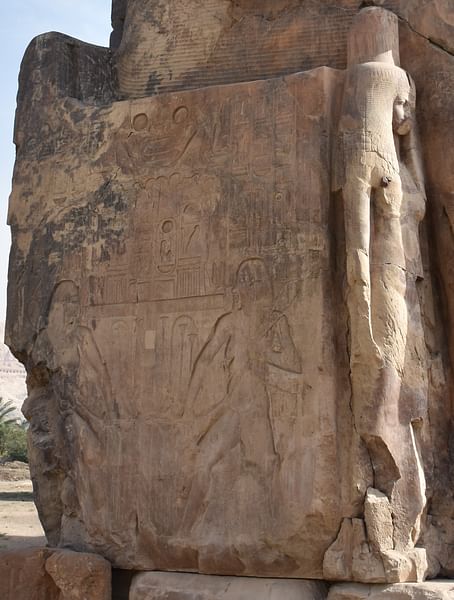

In their day, the guardians at the gate would have been clear depictions of Amenhotep III as god-king although they have sat in ruin now for centuries and, today, the figures are unrecognizable. He was deified in his lifetime and venerated by his own cult for centuries afterward. The base of the works depict his mother Mutemwiya and wife Tiye on the front and Hapy, the god of the Nile, on the side. All three of these figures symbolized rebirth. Gay Robins comments on the significance of the mother/wife figures:

Together these women represented the combined mother/consort role of the sky goddess through which the sun god renewed himself so that their presence symbolized the king's perpetual renewal through self-regeneration. (130)

Art in ancient Egypt was created to be functional and the Colossi are no exception. The statues would have served not only to guard the complex but, through a kind of sympathetic magic, allow the king to inhabit them and receive strength and sustenance from the symbolic imagery. The figures of Mutemwiya and Tiye are not just honorary ornamentation but served a specific purpose according to Egyptian belief. Mortuary statues placed in tombs were considered homes for the soul of the deceased when it visited earth and needed to be provided with food and drink offerings. In this same way, the Colossi were also thought to be more than simple stone images and especially after one of them began to sing.

The Singing Statue

The Greek historian Strabo (65 BCE-23 CE) is the first to record the sound which would later be described as singing, the sound of a lyre, brass instruments, a broken harp or lyre string, and a slap or blow. Strabo noted in his Geography that an earthquake shattered the upper part of the northern statue which, thereafter, made the noise every day at dawn. After visiting the site, Strabo writes:

Here are two colossi, which are near one another and are each made of a single stone; one of them is preserved, but the upper parts of the other, from the seat up, fell when an earthquake took place, so it is said. It is believed that once each day a noise, as of a slight blow, emanates from the part of the latter that remains on the throne and its base; and I too, when I was present at the place with Aelius Gallus and his crowd of associates, both friends and soldiers, heard the noise at about the first hour. (XVII.46)

Strabo adds that he cannot be sure where the sound came from, whether the statue itself, the base, or from one of the people standing nearby, but claims he will accept any explanation other than that of the stone image "speaking" in some way.

Many other ancient writers record the singing statue and the graffiti one may still see at the base records whether a visitor heard or did not hear the sound. People from all classes of society and regions traveled to the site for divination purposes, to ask a question and hope for the gods' answer, and would be rewarded - or disappointed - by the experience. This practice continued until the Roman emperor Septimus Severus (193-211 CE) visited in either 196 or 199 CE and did not hear the sound. Hoping to curry favor with the oracle, he had the northern statue repaired; afterwards, the sounds stopped completely.

It is popularly supposed that the sound was caused by dew drying inside the cracks of the statue and the porus rock was simply responding to the oncoming heat of the morning after a cool night. Similar "mysterious" sounds can be heard from objects like guard rails on roads between dawn and mid-morning in the present day.

Severus' repair of the statue sealed the cracks of the upper body and no doubt saved it from collapse but the site dwindled in popularity afterwards. With no miraculous oracle to answer their questions at the Memnonium, people went to other sites with their supplications and prayers. The site remained a tourist attraction, however, for the experience of seeing the enormous statues rising against the background of the far mountains and the ruins of the mortuary complex behind them. The site was already in ruin in Strabo's day and the temple and inner statues are now long gone but the Colossi of Memnon remain as reminders of the grandeur and vision of ancient Egypt.