A'Aru (The Field of Reeds) was the Egyptian afterlife, an idealized vision of one's life on earth (also known as Sekhet-A'Aru and translated as The Field of Rushes). Death was not the end of life but a transition to another part of one's eternal journey.

Everything thought to have been lost at death was returned and there was no pain and, obviously, no threat of death as one lived on in the presence of the gods, doing as one had done on earth, with everyone the soul had ever loved.

This vision developed slowly from the earliest periods of Egyptian history but was fully formed by the time of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) and developed further through elaborate texts in the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE). The soul was granted eternal paradise in A'Aru based on how virtuous the person had been in life and, after passing through judgment in the Hall of Truth, found peace everlasting in paradise.

Development

People already believed in the immortality of the soul and the survival of bodily death in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) as evidenced by grave goods included in burials. This belief developed throughout the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) and was fully integrated into the culture by the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE). Although some form of afterlife was envisioned from the earliest times, its details changed as the concept developed further.

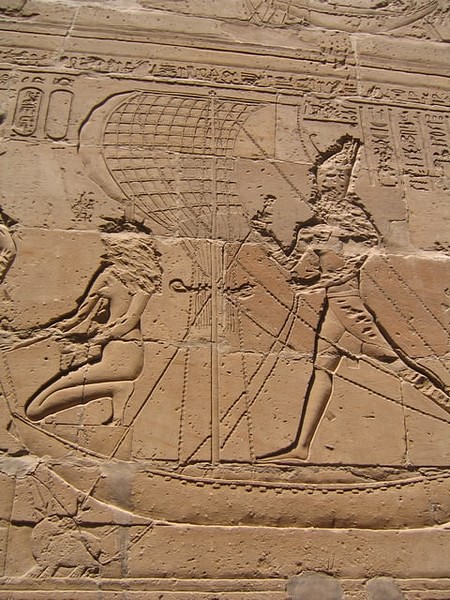

Initially, it seems the justified dead – those who had lived virtuous lives – were thought to live on in their tombs. Later, or perhaps even simultaneously, the belief arose that the souls of the righteous dead were lifted into the heavens by the sky goddess Nut to become stars. By the time of the Middle Kingdom, the cult of the god Osiris was firmly established and a more elaborate vision of the realm after death emerged which included a vast underworld known as Duat, judgment of the soul in the Hall of Truth by Osiris which included the weighing of the heart on the Scales of Justice, and eternal life in the Field of Reeds. The text known as The Book of the Heavenly Cow, parts of which date to the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE), references Ra (Atum) creating the Field of Reeds after deciding he will not destroy his human creations.

Egyptian religion was dynamic, changing by degrees during different time periods, and sometimes all of these visions of the afterlife were combined while, at others, one would dominate. In every era, however, a firm belief in life after death was central to Egyptian culture, the most enduring being the vision of A'Aru.

Religion

Religion was fully integrated into the lives of the ancient Egyptians. The gods were not faraway entities but lived close at hand in their temples, in trees, rivers, streams, and the earth itself. The gods had created order out of chaos in the dark beginnings of the world and had made Egypt the most perfect and pleasant land for humans to live in. Life in ancient Egypt was considered the best one could experience on earth - as long as one lived in accordance with the will of the gods.

Since the gods had given the Egyptians all good gifts, the people were expected to be grateful and show their thanks not only through worship and sacrifice but in their daily lives. Gratitude lightened the heart and made one content with what one had instead of envying the goods or lives of others. The central cultural value of the Egyptians was ma'at (harmony, balance), which was personified in the figure of the goddess of justice and harmony, Ma'at, depicted as a woman with a white ostrich feather (the feather of truth) above her head. If one lived with gratitude, one would be balanced in all things and this harmonious existence of the individual would encourage the same in those of one's family, one's immediate community, and finally the land at large.

There were no services as one experiences in modern-day religious practices as one's daily life was supposed to be an act of self-reflection, gratitude, repentance for wrong-doing, and resolve to live in accordance with ma'at. Scholar Margaret Bunson explains:

Religious beliefs were not codified in doctrines, tenets, or theologies. Most Egyptians did not long to explore the mystical or esoteric aspects of theology. The celebrations were sufficient, because they provided a profound sense of the spiritual and aroused an emotional response on the part of adorers. Hymns to the gods, processions and cultic celebrations, provided a continuing infusion of spiritual idealism into the daily life of the people. (228)

The king of Egypt (only known as “pharaoh” beginning with the New Kingdom) was thought to have been divinely appointed by the gods to rule the land and was supposed to embody ma'at as role model. The king was recognized as the intermediary between the gods and the people by the time of the Old Kingdom and would come to be associated with the sky god Horus (also known as Horus the Younger) while he lived and, after death, with Horus' father, Osiris, the righteous judge of the dead.

Osiris & Set

Osiris was one of the first five gods created at the beginning of the world. He was the firstborn, and then came Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus the Elder. The sun god Ra (in his form as Atum) had created the world with the help of the god of magic, Heka, and (in some versions of the story), the god of wisdom Thoth. After Ra had separated Nut, goddess of the sky, from her husband-brother Geb, god of the earth, he set Osiris and Isis to rule over Egypt.

The reign of Osiris and Isis was just and prosperous but Osiris' younger brother, Set, grew jealous and killed his brother, sealing him in a coffin which he threw into the River Nile. Isis went searching for her husband, found him, and brought him back to Egypt from Byblos, setting her sister Nephthys to guard the body while she went to pick herbs to return him to life. While she was gone, Set found the body, hacked it into pieces, and scattered it throughout the land. When Isis returned, she was heartbroken, but she and Nephthys, crying loudly, retrieved all the body parts and reassembled them except for the phallus which had been thrown into the Nile and eaten by a fish.

Prior to Osiris dismemberment, but after his death, Isis had lain with her husband and conceived Horus the Younger. Once Osiris was reassembled, he could no longer rule on earth because he was incomplete and so descended into the dark realm of Duat where he reigned as just judge and king of the dead. Isis and other goddesses (including Serket and Hathor) protected young Horus from Set until the child had grown. Horus then avenged his father, cast Set out of Egypt into the wild desert lands, and restored balance to the world, reigning in accordance with ma'at. This story was central to kingship in that the ruler was supposed to emulate Horus and the people would mirror the king's virtuous conduct.

Texts

This story comes from a manuscript from the 20th Dynasty (1090-1077 BCE) known as The Contendings of Horus and Set, but this is only the most complete version of a much older tale and the cult of Osiris (which would eventually become the cult of Isis) was already popular by the Middle Kingdom. The Contendings of Horus and Set is not a religious text in the same way one may think of that term in the present day. There was no “Bible” of ancient Egyptian religion. Stories like the murder of Osiris by Set, Horus' righteous conflict with his uncle, and the restoration of order were acted out at festivals throughout the year and these celebrations – which encouraged people to express their joy in living thorough feasting, drinking, dancing, and singing – served the purpose of religious instruction and expression. Bunson notes:

Festivals and rituals played a significant part in the early cultic practices in Egypt. Every festival celebrated a sacred or mythical time of cosmogonic importance and upheld religious teachings and time-honored beliefs. Such festivals renewed the awareness of the divine and symbolized the powers of renewal and the sense of the “other” in human affairs. (227)

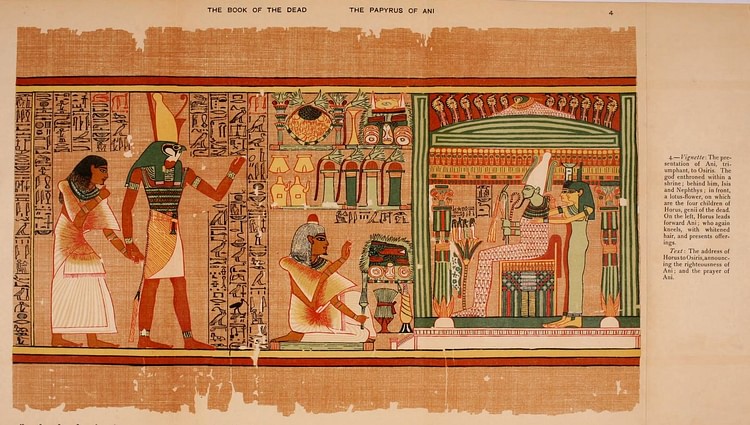

This awareness of the divine infusing daily life became central to the concept of the afterlife. Although ancient Egypt is often characterized as death-obsessed, the opposite is actually true: they were so aware of the beauty and goodness of life, they never wanted it to end and so envisioned an eternal realm which was a mirror-image of the life they knew and loved. This vision was developed through funerary inscriptions such as the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300 BCE), the Coffin Texts (c. 2134-2040 BCE), and finally culminated in The Egyptian Book of the Dead (“The Book of Coming Forth by Day”, c. 1550-1070 BCE). In addition to these, there was the Amduat (“That Which is in the Afterworld”) written in the New Kingdom, and others - also developed in the New Kingdom – The Book of Gates, The Book of Caverns, and The Book of Earth, all of which added to the vision of the afterlife and, when inscribed inside tombs, served to inform the soul of who it was and what it should do next.

Funerary Rituals & the Soul

Funerary rituals developed from primitive rites and modest preparation of the body to the elaborate tombs and mummification practices synonymous with ancient Egypt. At its most sophisticated (during the New Kingdom), the corpse of the newly deceased would be brought to the embalmers, who would prepare the body for burial. The body needed to be preserved because it was thought the soul would require it for sustenance in the afterlife. The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts:

- Khat was the physical body

- Ka was one's double-form

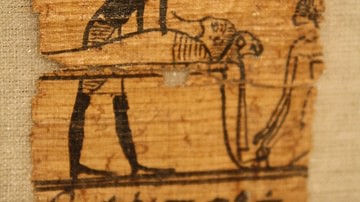

- Ba was a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens

- Shuyet was the shadow self

- Akh was the immortal, transformed self

- Sahu and Sechem were aspects of the Akh

- Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil

- Ren was one's secret name

The Khat needed to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and the Akh to proceed to paradise so the body had to be preserved as intact as possible. Once the body was prepared for burial, mourners would follow it to the tomb. Nobility and wealthy people began building their tombs while they were still alive so it would be ready when they needed it. Portions of the texts noted above would be inscribed on the walls and these were tailored to the individual tomb owner.

As the funeral procession moved along, professional mourners, known as The Kites of Nephthys (who were always women emulating the grief of Isis and Nephthys as they mourned Osiris), would wail and cry to encourage others to express their grief. This outpouring of emotion was thought to be heard and appreciated by the deceased who would be gratified they would be missed on earth, and this would enliven the soul. Once at the tomb, a priest would perform the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony in which he would touch the mummy's mouth (so it could speak) and arms and legs (so it could move) and then the tomb was sealed.

The Soul's Journey & the Hall of Truth

The mourners would then honor the dead with a ritual feast, often held right outside the tomb or at the home of the family. While they ate and drank, the soul of the deceased would rise from its body and would at first be confused. The texts on the walls would comfort the soul and instruct it. Anubis would appear to guide the soul from the tomb to a queue of souls standing in line awaiting judgment. As the soul waited, it would be comforted by various deities including Qebhet, Anubis' daughter, who brought the souls cool water to drink.

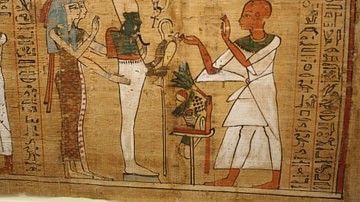

While waiting, the soul would know what to expect because of the texts: one would enter the Hall of Truth and see Osiris, Thoth, and Ma'at standing near the Scales of Justice as well as the deities known as The Forty-Two Judges who would have significant influence over one's fate. On the floor, below the Scales of Justice, would be the monster Ammut (part lion, part hippopotamus, part crocodile) waiting to eat the heart of the unjust who were judged unworthy of paradise.

When one's turn came, the soul would enter the Hall of Truth and address the Forty-Two Judges by their secret name (their ren) and then recite the Negative Confession (also known as The Declaration of Innocence), a list of forty-two sins one had not committed. The Negative Confession was written for each specific individual. A merchant would not have been tempted toward the same types of sins as a soldier or an artisan. The best-known confession comes from The Papyrus of Ani, a text of the Book of the Dead, and appears in Spell 125 which also relates the other aspects of judgment in the Hall of Truth.

Having recited the confession, one presented one's heart to be weighed on the golden scales against the white feather of Ma'at. If one's heart was heavier than the feather, it was dropped to the floor and devoured by Ammut; if the heart was lighter, and after Osiris conferred with the Forty-Two Judges and Thoth, one was justified and could move on toward the Field of Reeds.

The Field of Reeds

As with all aspects of Egyptian religion, what happened next depends on which text one reads and the period of history in which it was written. In some versions, the soul still has to dodge various traps and pitfalls. The most common version has the soul leave the Hall of Truth and walk to Lily Lake, where it encounters the entity known as Hraf-haf (“He Who Looks Behind Him”), an obnoxious and surly ferryman. The soul would need to find some way to be kind and courteous to Hraf-haf, even though he would do nothing to encourage this, and if one passed this final test, one would be rowed across the water to the shores of the Field of Reeds.

Once there, the soul would find everything thought to have been lost at death. One's home would be there, just as one left it, as well as all those loved ones who had passed on before and even one's favorite dog or cat or other pets. The tree one enjoyed sitting under or the stream one used to walk by would be there, and one would live eternally in the presence of the gods. Just as Horus had defeated Set to establish the ordered world the soul had left, the justified soul defeated death and found perpetual paradise in the afterlife. Scholar Rosalie David describes the land:

The inhabitants were believed to enjoy eternal springtime, unfailing harvests, and no pain or suffering. The land was democratically divided into equal plots that the rich and poor alike were expected to cultivate. (Handbook, 142)

The eternal aspect of the Field of Reeds was not uniform in every era, however. During the Middle Kingdom, a cynical religious skepticism appears in Egyptian literature which may, or may not, echo the actual belief of the time. Scholar Geraldine Pinch describes the temporal view of paradise engendered by this cynicism:

The soul might experience life in the Field of Reeds, a paradise similar to Egypt, but this was not a permanent state. When the night sun passed on, darkness and death returned. The star-spirits were destroyed at dawn and reborn each night. Even the evil dead, the Enemies of Ra, continuously came back to life like Apophis so that they could be tortured and killed again. (94)

This view was not the dominant one, however. Throughout most of Egypt's history, the Field of Reeds was the everlasting home of the justified soul. This vision of paradise is probably best expressed today in the last lines of the Christian hymn Be Still My Soul:

Be still, my soul, when change and tears are past

All safe and blessed, we shall meet at last. (Hymn 370)

The soul, having passed through the trials and joys of life on earth, and justified by the gods for its virtuous adherence to ma'at, found peace in an unchanging reflection of the world it had never wanted to leave behind. Here was work but no toil and love without the threat of loss. All one had mourned was returned, and every prayer was answered in that one could enjoy the best moments of one's life without them ever passing into memory. All the inspiring festivals and every cherished moment with those one loved were returned, and the soul rejoiced in knowing that death was not a loss at all but only the next phase of one's eternal life.