Claude Brousson (l. 1647-1698) was a prolific writer and famous preacher after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 when Protestantism was outlawed in France. He self-exiled to Lausanne and Holland and returned to France to preach and organize illegal nighttime gatherings. After years of clandestine ministry, Brousson was arrested and executed at Montpellier on 4 November 1698.

Historical Context

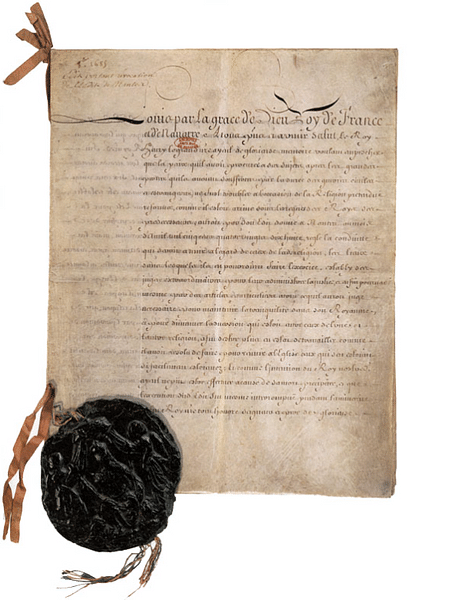

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century began a period of turmoil in Europe that would destabilize nations and disrupt the religious monopoly held by the Roman Catholic Church. The Reformation in France enjoyed great success in the poorer and more remote provinces of Languedoc and Dauphiné and led to a religious and social revolution. Protestants considered religious liberty a divine right and sought to remain faithful subjects of the king and faithful to God according to their understanding of the Scriptures. This right was contested by Catholic and royal opposition and led to the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598). The wars ended when the Protestant Henry of Navarre converted to Catholicism and was crowned Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610). Under Henry IV and the Edict of Nantes, Protestants were granted limited freedom to practice their religion in 1598. The edict was enforced during the reign of Henry IV, at times with great difficulty, until his assassination on 14 May 1610. The right of Protestants to worship God according to their conscience was undermined in the 17th century, first by Henry's son, Louis XIII (r. 1610-1643), and then by Henry's grandson Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715).

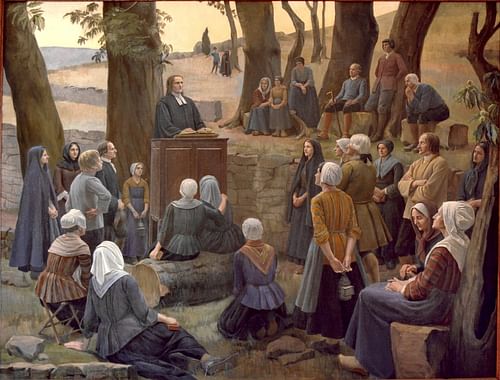

Protestants owed the recognition of their rights more to sovereign decrees than to genuine tolerance or religious pluralism. Louis XIV initially thought that strict respect for previous edicts and the refusal to grant additional rights was the most effective way to reduce the number of Protestants in his kingdom. He finally yielded to the Catholic clergy's pressure to obtain the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes on 18 October 1685, also known as the Edict of Fontainebleau. The king's subjects were compelled to adopt the religion of the king, and with the reign of Louis XIV and the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Protestants lost the rights gained under Henry IV. Following the revocation, an estimated three-fourths of Protestants renounced their faith. Those who remained in the south of France worshipped illegally, some in homes, others in secret places. The death penalty was pronounced in July 1686 against pastors who returned from exile, the king's galleys the fate of men who lent them assistance, and execution or imprisonment for anyone caught in an illegal assembly.

Early Life & Ministry

Claude Brousson was born in 1647 at Nîmes to Protestant parents, Jean Brousson and Jeanne de Paradez. He was the second son among the couple's nine children, most of whom died at an early age. His early education at the Collège de Nîmes was followed by studies at the Académie Protestante de Nîmes where he studied Latin, rhetoric, philosophy, and human sciences. He earned his Master of Philosophy in 1664 and a doctorate in law in 1666. In 1678, he married Marie de Combelles of Béziers, established himself in Toulouse as a lawyer in the Parlement of Toulouse, and served as an elder in the local Reformed church. For many years, he defended the poor and Reformed churches before the courts and came close to losing his employment because of his devotion to the Reformed faith.

Before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Brousson held to the myth that the repressive measures in Languedoc in southern France were done without Louis XIV's consent. When Brousson saw that legal recourse failed to stop religious repression, he endeavored to draw the king's attention to the plight of Protestants. In 1683, he planned a peaceful gathering of Protestants and met secretly with 28 deputies of churches of Languedoc. It was decided that in those places where Reformed worship was forbidden, Protestants would gather publicly on an appointed day. To avoid a massacre, Brousson advised the attendees to come unarmed. He understood the dangers and saw this as the least dangerous course of action. The undertaking failed for several reasons, principally because of the dissension between the reluctant urban elite and the more determined common people from the countryside.

Several regions refused to participate in the public manifestation; the churches of Haut- and Bas-Languedoc and the consistories of Castres and Nîmes opposed even peaceful resistance. Despite the opposition, the towns and villages of Dauphiné, Vivarais, and the Cévennes seized the opportunity to gather at their dilapidated temples. A few days later, church representatives assembled to declare both their loyalty to the king and their intention to defend the freedom of conscience granted by the Edict of Nantes. Violence broke out in August when Catholics tried to forcibly prevent Reformed worship in public. In response, Protestants attempted to recruit thousands of men for armed resistance. The authorities dispatched soldiers, leading to a clash between the royal troops and Protestants. 50 men were hanged and two pastors were condemned to the wheel. Many pastors fled to Switzerland where Brousson also found refuge. From there, he went to Holland and published a defense of his failed project, and using extensive biblical references, he linked the suffering of Protestants to those of ancient Israel.

After the revocation, Protestants were left with the choice of submission, exile, clandestinity, or resistance. Those who refused to submit were met with severe repressive measures – confiscation of property, child kidnapping, forced lodging of soldiers in their homes, death for those caught in illegal assemblies, and prison or the kings' galleys for those who sought to flee the kingdom. Despite the threats, thousands fled to find refuge in Protestant lands.

Return from Exile

In exile, Brousson studied the Book of Revelation of the New Testament and found the source for his thunderous warnings and calls to repentance for Protestants who had returned to the Catholic Church and sent thousands of sermon pamphlets to Languedoc. Despite the danger that awaited him, he returned to the Cévennes in 1689. Another returnee was François Vivent (l. 1664-1692), who had received ordination while in exile and became pastor of the Church of the Desert. The Church of the Desert recalled the wilderness wanderings of the people of Israel after their exodus from Egypt and came to designate the period when the Reformed religion was outlawed in France. When Brousson and Vivent arrived in the Cévennes they called an assembly and organized a day of fasting and repentance. Amazed at the people's zeal, they were persuaded that by taking up arms, they could hasten the deliverance of the true church.

Brousson and Vivent also addressed what has been called a 'prophetic epidemic'. In the absence of pastors, prophets and prophetesses proliferated in Dauphiné, Vivarais, and the Cévennes. In the beginning, these self-appointed leaders preached the Bible, exhorted people to repentance, and promised them freedom. Over time the message turned to armed resistance. Not all Protestants supported Brousson, Vivent, and the Church of the Desert. The church was mostly composed of the lower classes of society – artisans, sheep and goat herders, and farmers. The Protestant nobility was virtually absent. Most pastors in exile disapproved of the public gatherings and recommended family worship and patience.

Vivent consecrated Brousson to the pastoral ministry before Vivent went to Bas-Languedoc and Brousson remained in the Cévennes. He wandered from place to place, traveled great distances, and held assemblies. Through his social origin and professional training, Brousson was by far the most educated and most qualified to lead in reestablishing the ruined structures of the Reformed Church. He wrote out the sermons of others with an apocalyptic emphasis. The image of the desert, a place of trials and suffering, was prominent in his messages. Brousson also intended to join the coalition of William III of England (l. 1650-1702) in the hope of fomenting an insurrection. He and Vivent were in regular contact with friends in Switzerland and government leaders in England and Holland to request foreign intervention. A price was put on both their heads by the king's steward. Vivent was killed in a cave defending himself in February 1692, and his four companions were captured and hanged.

After Vivent's death, Brousson remained the only leader of the Church of the Desert. Over time, however, he turned from armed resistance to spiritual resistance. When the army of the Duke of Schomberg penetrated Dauphiné in the summer of 1692, Brousson prevented the Cévenols from participating in an uprising, and the duke's army returned home. Brousson wrote letters to the king and the provincial governor. He was pursued by the king's troops and again found refuge in Holland. Many preachers were captured, yet the resistance and the illegal assemblies multiplied.

Arrest & Death

While Brousson was in Holland, the Treaty of Rijswijk in 1697 ended Louis XIV's war against an alliance of England, Holland, and Austria. Rumors circulated that the French king was prepared to offer clemency to Protestants and allow them to gather for worship in their homes, bury their dead in public cemeteries, have their marriages blessed, and permit his subjects to practice the religion of their choice. In truth, the king had not consented to any of these measures. Brousson returned to Languedoc in 1698 where the forced housing of the king's troops (dragonnades) had restarted in the homes of Protestants.

In the Cévennes, soldiers went house to house searching for weapons and heretical books. Those found in possession of them were condemned to fines or the king's galleys. People were forcefully escorted to Mass by soldiers and fined for refusing to send their children to catechism. Brousson finally realized that the king himself was responsible for the persecution and not only the governors of the provinces. With this conviction, he once again wrote the king a series of petitions and sent them to other provinces and countries to influence public opinion. The king's regional steward distributed Brousson's portrait throughout Languedoc. He was recognized, arrested, and imprisoned, then escorted to Montpellier to stand in judgment. Brousson admitted the charges against him, that he had preached throughout the province, held communion services, and baptized infants. He was condemned to be broken on the wheel and strangled to prevent him from speaking. According to a contemporary, Brousson walked to his execution as if going to a feast.

There would be other arrests and executions. Only a shadow remained of the Church of the Desert. The last preachers fled the kingdom in 1699, and Protestants were once again left without their shepherds. In their place would arise prophets and the return of violence with the War of the Camisards in 1702.