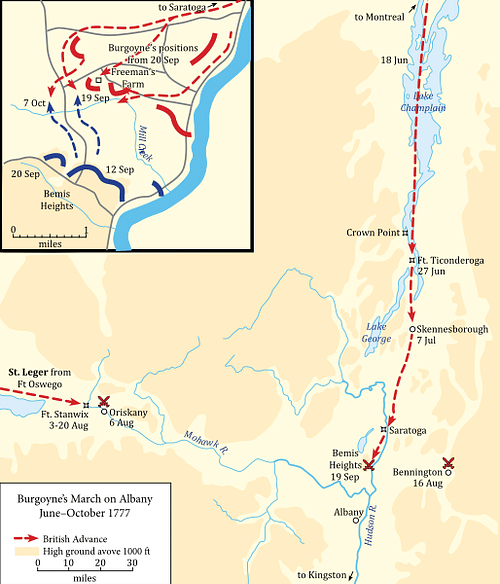

The Saratoga Campaign (20 June to 17 October 1777) was one of the most important military campaigns of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), in which a British army under General John Burgoyne invaded the Hudson River Valley but was defeated by an American force at the Battles of Saratoga. The surrender of Burgoyne's army convinced France to enter the war.

British Plans

In early 1777, as the American Revolutionary War approached its third year, British colonial secretary Lord George Germain racked his brain for new strategies with which to crush the American rebellion. The path to victory was not so clear as it had once appeared. Indeed, despite the major British successes of the previous year – including the Battle of Long Island and the capture of New York City – the war seemed no closer to being over. The American Continental Army under George Washington remained intact, bruised from the previous year's campaign but still spoiling for a fight, while the Second Continental Congress continued to mock royal authority from Philadelphia. To win the war, Lord Germain decided, the fledgling United States would have to be suffocated, and there was already a man in London with a plan for such an action.

General John Burgoyne was a man of many talents. A notable playwright, he was also a well-bred aristocrat with political ambitions; indeed, his charming aristocratic demeanor had led his soldiers to affectionately nickname him 'Gentleman Johnny'. Having served during the past two years as one of the top British field commanders in America, Burgoyne now hungered for an independent command of his own. Over lunches with Lord Germain and horseback rides with King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820), Burgoyne sketched out a plan for a decisive campaign that he claimed would win the war. It was to be a two-pronged offensive: one British army would march south from Canada, seizing the critical Fort Ticonderoga before continuing along the Hudson River to capture Albany, New York. A secondary British force, also departing from Canada, would advance along the western Mohawk River before linking up with the main army at Albany. The capture of the Hudson would, at least theoretically, sever communication between the northern and southern colonies and isolate New England, considered the heart and soul of the rebellion.

The aggressiveness of the plan appealed to the king and Lord Germain, who had both grown tired of the timidity shown by other British generals. They not only approved the expedition but also appointed Burgoyne to lead it. Lord Germain then wrote to Sir William Howe, commander of the main British army in New York City, asking him to support the expedition by pushing north and linking up with Burgoyne at Albany. Howe had little interest in supporting a campaign in which the lion's share of the glory would fall to Burgoyne, and instead, he planned a campaign of his own, in which he hoped to capture the United States capital of Philadelphia and defeat George Washington's army; this would make Howe, not Burgoyne, the hero of the war. Still, Howe made sure to soothe Germain's concerns by promising to march to Burgoyne's aid after he had seized Philadelphia, leading the colonial secretary to accept his plan.

Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

On 6 May 1777, General Burgoyne arrived back in Canada to find that his army of 8,300 men had already been assembled. It was a formidable invasion force consisting of 3,700 British regulars, 3,000 professional German soldiers, 650 Canadian militia, 400 Iroquois, and 138 artillery pieces, manned by 600 artillerymen. His officer corps, too, was quite respectable, consisting of Major General William Phillips as his second-in-command (once described by Thomas Jefferson as the proudest man in the proudest nation on Earth), Brigadier General Simon Fraser as commander of the advance guard, and Baron Friedrich Adolf von Riedesel in charge of the Germans. On 20 June, Burgoyne's expedition set out in boats down Lake Champlain; simultaneously, a secondary 1,800-man expedition under Colonel Barry St. Leger landed at Oswego, New York, to begin the conquest of the Mohawk River Valley.

Burgoyne disembarked his army at Crown Point, 8 miles (13 km) to the north of his first objective, Fort Ticonderoga. Despite the fort's reputation as the key to the north, the Americans had allowed its principal fortifications to slip into a state of disrepair. The fort was inadequately supplied, and its garrison of 2,700 men was rapidly shrinking due to disease and desertion; the American commander, General Arthur St. Clair, knew he did not have enough resources to defend both Ticonderoga itself and the secondary fortifications on Mount Independence, just across the lake. When Burgoyne's army marched into view on 1 July, therefore, St. Clair was faced with an unpleasant dilemma: defend the fort in what was certainly a losing battle or abandon it to save his men. The decision was made easier on 5 July, when the British placed cannons atop the 750-foot (230 m) Sugar Loaf Hill, which overlooked both Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. Unwilling to subject his men to an artillery bombardment, St. Clair evacuated.

Hubbardton & Fort Anne

That night, the Americans loaded their ammunition, provisions, and most of their sick into bateaux and set sail for Skenesborough (now Whitehall) at the southern end of Lake Champlain. St. Clair led the remaining 2,000 men in an eastward retreat, into the territory known as the New Hampshire Grants (modern Vermont). When the British awoke on the morning of 6 July, they were surprised to find Fort Ticonderoga empty; an elated Burgoyne immediately occupied the fort and sent his advance guard under General Fraser in pursuit of St. Clair's retreating garrison. Fraser's 850 men spent all day on a quick march, allowing them to catch the American rearguard at the small town of Hubbardton early the next morning. The 1,000-man American rearguard, commanded by Colonel Seth Warner, stood its ground, leading to a bitter, three-hour firefight. For a while, neither side could gain the upper hand until the sudden blaring of a military band announced the arrival of Baron Riedesel and 1,200 German troops. The Germans, armed with their short, accurate rifles, were able to envelop the American flank and send them running into the woods.

While Fraser and Riedesel were battling with St. Clair's rearguard at Hubbardton, the American bateaux were rowing for their lives across Lake Champlain, with Burgoyne's main force in hot pursuit. The Americans, led by Colonel Pierse Long, finally disembarked at Skenesborough before sheltering in the nearby Fort Anne, where they were joined by 400 New York militiamen under Henry Van Rensselaer. Burgoyne sent a detachment of British troops after Long and Van Rensselaer, leading to another bloody battle on 8 July at Fort Anne. The Americans held out until nightfall, burning the fort before slipping away into the night. On 12 July, Colonel Long linked up with St. Clair's main American army at Fort Edward, on the edge of the Hudson River, as Burgoyne set up headquarters at Skenesborough.

Burgoyne was in no hurry to leave. He was hosted by the town's leading citizen, Loyalist Philip Skene, who graciously turned a blind eye to Burgoyne's dalliances with his wife. 'Gentleman Johnny' had clearly become overconfident from his recent successes, penning a letter to Lord Germain in which he gleefully predicted the fall of New England before the end of the summer. It was around this time that Burgoyne learned that Howe had not yet even set off for Philadelphia, making it unlikely that he would be able to support Burgoyne's expedition at all; so much the better for Burgoyne, who would not have to share any of the glory for his impending victory.

St. Leger's Expedition

On 26 July, the second British expedition under Colonel Barry St. Leger was getting underway. Of the 1,800 men who marched with St. Leger, around 800 were Iroquois; led by Iroquois chiefs Joseph Brant, Cornplanter, and Sayenqueraghta were warriors from the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga nations. Guided by Iroquois scouts, St. Leger's expedition marched to Fort Stanwix on the Mohawk River, which they besieged on 2 August. Fort Stanwix was defended by 750 militiamen under Colonel Peter Gansevoort, who was determined to hold the fort at all costs. Gansevoort appealed to the Tryon County militia for help, and his call was answered by Brigadier General Nicholas Herkimer, who gathered 800 men and marched off to the relief of Fort Stanwix; Herkimer's force included around 100 Oneida warriors.

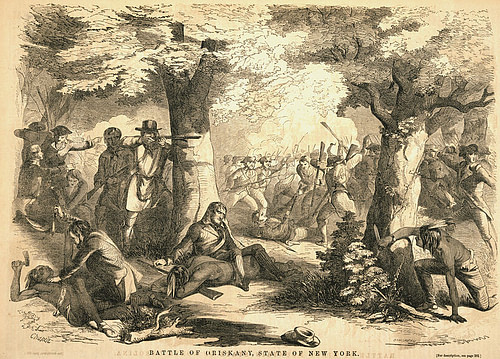

On 6 August, Herkimer was marching through the village of Oriskany, only 10 miles (16 km) southeast of Fort Stanwix, when he was ambushed by a party of Loyalist and Iroquois troops led by Joseph Brant. The ensuing battle lasted for several grueling hours before Brant's warriors slipped back into the woods. By then, nearly half of the Patriot force had been killed or wounded, including Herkimer himself, who received a mortal wound, and the Patriot column was eliminated as a fighting force. Brant's Iroquois warriors had also suffered severe casualties during the battle and had, moreover, been forced to fight and kill their Oneida brethren (the Oneida were one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois). In retaliation for this betrayal, Brant soon led his Mohawks in a raid against the Oneida village of Oriska, leading the Oneidas to attack several Mohawk settlements; the Battle of Oriskany had, therefore, triggered a civil war amongst the Iroquois.

Meanwhile, although St. Leger continued his siege, he was feeling quite exposed, anxious that another Patriot force would emerge from the woods any day. His worst fears appeared to be realized in mid-August when several Loyalist scouts reported that Patriot General Benedict Arnold was marching toward Fort Stanwix with a large relief force; on 22 August, unwilling to be caught between Arnold's force and the fort, St. Leger decided to lift the siege and retreat to Canada. Several days after the British had gone, Arnold arrived and greeted the thankful Colonel Gansevoort, who was surprised to find that the American general had less than 100 men. With a smile, Arnold explained how he had planted false clues to trick the Loyalist scouts into thinking he had a much larger force. It was with deception, therefore, that Arnold had saved Fort Stanwix.

Bennington

In mid-July, General Burgoyne set out from Skenesborough, only to find the road to Fort Edward obstructed; Patriot militias had destroyed bridges and blocked roads with boulders and felled trees, slowing the British advance to a crawl. When on 29 July, the British finally arrived at Fort Edward, it was empty – St. Clair and his Patriot troops had long since evacuated – and there were no provisions, but Burgoyne had made it to the Hudson River. However, all feelings of success were soon overshadowed by the murder of Jane McCrea, the American wife of one of Burgoyne's Loyalist officers. McCrea's scalped corpse was discovered just outside Fort Edward, and word quickly spread that she had been killed by a Native American warrior serving with the British. For Burgoyne, who had hoped to galvanize Loyalist support in the region, this was a public relations nightmare. The Patriots wasted no time propagandizing the murder, using it as evidence that Burgoyne could not control his indigenous allies, whom he supposedly planned to unleash upon American settlements.

Before Burgoyne could deal with the ramifications of McCrea's death, he was faced with a much more pressing concern: the British army was running dangerously low on every kind of provision except gunpowder. On 11 August, Burgoyne dispatched 600 Germans under Lieutenant Colonel Friederich Baum to scour the countryside in search of food. Baum led his troops to the town of Bennington (in modern Vermont), where they expected to find a large number of Loyalist sympathizers; instead, the Germans ran straight into a Patriot militia force under General John Stark, which quickly enveloped them. In the ensuing Battle of Bennington (15 August), Baum was killed, and his entire force was eliminated; when a second German force of 600 men arrived on the battlefield to reinforce Baum, it, too, was badly mauled by the Patriot forces. In all, nearly 1,000 Germans were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner.

Burgoyne learned of the defeat at Bennington on 17 August, around the same time that he learned of St. Leger's failure to take Fort Stanwix. What was more, Burgoyne's indigenous allies had become incensed by the treatment they had received after McCrea's murder and begun to desert in droves, depriving the British of sorely needed scouts. At this junction, Burgoyne's path of retreat remained wide open, but this was not an option that the general dared consider. Instead, he continued pushing south along the Hudson, hoping to find the supplies he desperately needed when he reached Albany.

Saratoga

Between 13 and 15 September, Burgoyne crossed over to the west side of the Hudson River at Saratoga; the British army now totaled around 7,000 men. It was then that Burgoyne learned that the Northern Department of the Continental Army, commanded by General Horatio Gates, had occupied the nearby Bemis Heights, which rose 200 feet (60 m) above the river and were covered by dense forest and rough terrain. At the top, the Americans sheltered behind a series of earthen fortifications constructed by Polish engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko. In all, the Continentals had around 8,500 battle-ready men.

Burgoyne knew he had to roll the Americans off the heights to continue his push toward Albany. On the morning of 19 September, he ordered an attack, relying on a detachment of troops under General Fraser to swing around the American left flank and push Gates' army into the river. As the British began their march, Benedict Arnold, who had just rejoined the main American army from Fort Stanwix, recognized the danger of a British flanking maneuver. Accompanied by Daniel Morgan's Virginia riflemen and Henry Dearborn's light infantry, Arnold occupied Freeman's Farm where he awaited the British advance. When Fraser's column approached their position, the Patriots opened fire, beginning the Battle of Freeman's Farm (or the First Battle of Saratoga). Arnold's troops withstood hours of musket volleys and bayonet charges; it was only after the fall of darkness that they pulled back to the safety of Bemis Heights. The British attack had been stalled, at the cost of 556 British and 319 American casualties.

For the next few weeks, neither army moved, with both Burgoyne and Gates waiting for the other to make the first move. Time was not on the British side, however; thousands of Patriots, inspired by the recent victories at Bennington and Freeman's Farm, arrived on Bemis Heights to enlist in Gates' army. By contrast, Burgoyne was losing men every day, with British troops dying of their wounds or deserting. To make matters worse, Patriot General Benjamin Lincoln had gathered 2,000 New England militiamen and retaken Fort Ticonderoga on 18 September, thereby cutting off the redcoats' route of retreat. Burgoyne now had no choice but to reach Albany.

There was one last ray of hope for the faltering British expedition. On 3 October, Sir Henry Clinton, commander of the British garrison in New York City, sailed up the Hudson with 3,000 men. On 6 October, Clinton captured the two Patriot forts Montgomery and Clinton in the New York highlands, before dismantling the chain across the Hudson River and burning the town of Kingston, provisional capital of New York State. The hope was that General Clinton could make enough of a fuss to pull Gates' army off Bemis Heights and allow Burgoyne to continue on to Albany; but Gates refused to take the bait, and stayed put. The only solution was for Burgoyne to attack.

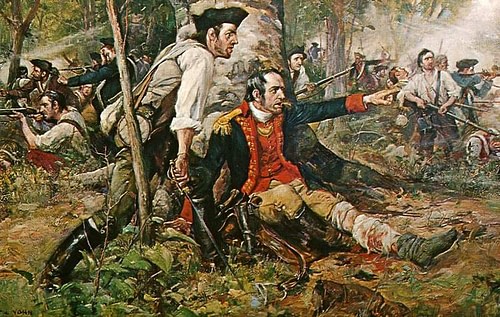

On 7 October, Burgoyne sent out General Fraser with a reconnaissance force to probe the American left; if it detected any weakness at all, Burgoyne would attack with his entire army. The British detachment was intercepted by the Americans, leading to the Battle of Bemis Heights (or Second Saratoga). In the ensuing fight, Fraser was killed, and the British were pushed back to their redoubts. With Arnold in the lead, the Patriots stormed the British position; Arnold was wounded in the leg, but his men successfully captured one of the British redoubts. By nightfall, around 900 British had been killed, wounded, or captured, compared to only 150 American casualties.

Surrender

On 8 October, the British army attempted a northerly retreat, but a sudden storm prevented them from escaping. Instead, Burgoyne ordered his tired and hungry army to dig in near the town of Saratoga, in the desperate hope that Clinton's army would come to their rescue. However, it became apparent that this would not happen, and Burgoyne entered negotiations with General Gates. Gates, who was eager to bring the matter to an end, granted the British surprisingly lenient terms, promising that, in return for their surrender, they would be permitted to leave for England. Burgoyne agreed and surrendered his army on 17 October 1777, with the full honors of war, as military bands played 'Yankee Doodle' and 'The British Grenadiers'. When the Continental Congress learned about the overly lenient terms Burgoyne had been granted, it overrode them; instead of leaving for England, the British army was imprisoned in Virginia, where it would sit out the rest of the war.

The Saratoga Campaign marked the first time an entire British army had surrendered to the Americans. Moreover, it made an impression on the French foreign ministry, which had been watching the war closely; France immediately entered talks with Congress about a potential alliance and officially joined the war in early 1778.