The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga (10 May 1775) was a military operation that occurred early in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). A small colonial expedition jointly led by Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen surprised the British garrison of Fort Ticonderoga, seizing both the fort and its artillery. The Americans later used the captured cannons to win the Siege of Boston.

Fort Ticonderoga

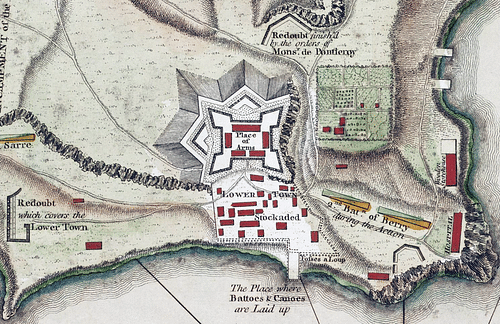

Fort Ticonderoga sits at the southern end of Lake Champlain, near the modern-day border between New York State and Vermont. Its location was of critical significance for the colonial wars of the 18th century, as it guarded a major system of rivers and lakes that connected New York City to Quebec. This waterway – comprised of the Hudson River, Lake George, Lake Champlain, the Richelieu River, and the Saint Lawrence River – was a nearly unbroken chain of bodies of water with only a handful of portages that had long been utilized by the Native Americans for travel purposes. The colonial empires of Britain and France considered the passage to be the 'American jugular', the key to the continent; if the British controlled it, for instance, they could invade France's colony of Canada, while the French could use the waterway to attack the interior of Britain's Thirteen Colonies.

In 1755, the French constructed a large star-shaped fortress, named Fort Carillon, at the key juncture between Lake George and Lake Champlain. The ongoing French and Indian War (1754-1763) marked the climactic struggle between the two colonial powers for dominance of North America, and the British knew they had to capture Fort Carillon as a prerequisite for an invasion of Canada. In 1758, a British expedition of 16,000 regular and provincial troops set out to conquer the fort but was repulsed by 4,000 French defenders. The Battle of Carillon was the largest and bloodiest battle fought on North American soil until that point. It also gave the fort a reputation for impregnability, even though most of the fighting had taken place about a mile away from the fort itself. After the battle, the French reduced the fort's garrison to only 400 men, leaving it vulnerable to another British expedition of 11,000 men the following year. Realizing they had no chance against the large British force, the French garrison decided to abandon Carillon, but not before spiking the guns and destroying much of the fort with explosives.

The British captured the ruined fort and renamed it Ticonderoga, which was derived from an Iroquois word meaning "between two waters" or "where the waters meet" (history.com). The British spent the next several years working to rebuild and improve the fort. But at the end of the war in 1763, France ceded Canada to Britain, which negated Fort Ticonderoga's strategic importance because the New York – Canada water route was now entirely within British territory. The British, therefore, did not prioritize the fort's upkeep and, by 1775, it had fallen into a state of semi-disrepair, with the walls, bastions, and blockhouses in a dilapidated condition. It was garrisoned by a skeleton force of 2 officers and 48 men and was also the home of their families, which included 24 women and children. This garrison was much too small to defend the fort from attack but was deemed suitable to watch over it during peacetime. But in early 1775, the clouds of war were quickly gathering, and Ticonderoga was woefully unprepared for the storm.

Arnold's Idea

By March 1775, tensions between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies had been rising for over a decade; the recent implementation of the Intolerable Acts by the British Parliament practically guaranteed that war would soon break out, and militias across the New England colonies were preparing for conflict with British soldiers. At Ticonderoga, the garrison's commander, Captain William Delaplace, noticed suspicious activity by American Patriots in the region and wrote to his superior, General Thomas Gage, to voice his concerns. Gage, however, had his hands full dealing with the fallout of the Intolerable Acts in Boston and brushed off Delaplace's concerns. After all, Ticonderoga still enjoyed its reputation of impregnability and was even referred to as the 'Gibraltar of North America'; how could the backwoods Americans even dare to attack such a mighty fort? But on 19 April 1775, after the first shots of the war were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Gage and his small army of British soldiers found themselves trapped in Boston by over 15,000 Patriot militiamen. Realizing he had misjudged the Patriots' resolve, Gage wrote a letter to the governor of Canada, urging him to send reinforcements to Ticonderoga. The letter would not arrive in Montreal until late May, however, by which point it was much too late.

In the days after Lexington, New England militias continued to arrive at the Patriot headquarters of Cambridge, Massachusetts, to add their strength to the rebel army. One such militia, from New Haven, Connecticut, was eager to fight the British; they had been constantly drilling for over a month, trained by their captain, a dashing 35-year-old merchant and Son of Liberty named Benedict Arnold. Dressed in the resplendent scarlet uniform of the New Haven militia, Arnold was riding ahead of his men when he encountered an old colleague, Samuel H. Parsons, who was riding the opposite way, coming from Cambridge and headed for Hartford, Connecticut. When Arnold asked for news about the Patriot headquarters, Parsons told him that the New England army vastly outnumbered the British in Boston but would not be able to drive them out due to a lack of ammunition and artillery. Arnold replied that he knew where to find both – his travels had often taken him to the vicinity of Ticonderoga in New York, where he knew the British stored an arsenal of cannons, howitzers, mortars, and lots of powder. The two men parted ways, but the idea of Ticonderoga remained in each man's head.

When Parsons arrived in Hartford, he presented himself before the Connecticut Committee of Correspondence and relayed the information he had learned from Arnold. The committee was greatly intrigued by this information – it had recently heard a report from John Brown, a Massachusetts spy, detailing the strategic location of the fort. These two factors led the committee to commission an expedition to capture Ticonderoga, which it wanted Ethan Allen to lead. Allen was a tall and burly frontiersman who was initially from Lichfield, Connecticut, but had since settled in the disputed territory known as the New Hampshire Grants (modern Vermont). The Grants had been claimed by both New York and New Hampshire, leading to conflict between the colonies. To protect their lands from the encroachment of New York's royal governor, William Tryon, Allen and other settlers had formed a militia, calling themselves the Green Mountain Boys. The Green Mountain Boys' conflict with Governor Tryon led them to despise royal authority. So, when the Connecticut Committee asked for their help in capturing Ticonderoga, Allen and the Green Mountain Boys readily agreed.

Arnold, meanwhile, arrived at the Patriot headquarters of Cambridge, where he quickly sought an audience with Dr. Joseph Warren, president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, and General Artemas Ward, commander of the makeshift army. After explaining what he knew about the guns and ammunition at Ticonderoga, Arnold requested to lead an expedition to capture the fort; this was granted, and he was given the rank of colonel, as well as £100 for recruitment purposes. Eager to make a name for himself, Arnold immediately left Cambridge to begin preparing for the expedition, only to learn that Ethan Allen had already been tasked with the same goal by the Connecticut committee. Arnold was not about to give up his chance at glory and raced to Allen's headquarters at Bennington (in modern Vermont) to assert his authority over the mission.

Preparations

Arnold arrived at Bennington on the evening of 6 May and entered the Catamount Tavern, where the Green Mountain Boys held their meetings. Dressed in the scarlet uniform of the New Haven militia, Arnold was mistaken for a British officer, and the Green Mountain Boys pointed their weapons at him as soon as he walked through the door. Luckily, Arnold carried his orders from General Ward in his pocket and was thereby able to diffuse the situation by proving his identity. But the hot-headed Arnold risked provoking the Green Mountain Boys again when he demanded their obedience, claiming that his authority was derived from his commission in the New England army. The rough-and-tumble Vermonters only laughed at this claim. They had been promised the right to elect their own officers and had already elected Ethan Allen; they would all go home rather than serve under anyone else. When Arnold asked where Allen was, he was told that the frontiersman was at Castleton, New York, preparing the expedition. Arnold left immediately, determined to lead the expedition at all costs.

Arnold arrived at Castleton on 8 May and reiterated his claims before Allen himself. Once again, the Green Mountain Boys threatened to mutiny rather than serve under anyone except Allen, but Arnold was insistent, brandishing his orders from the New England army. Eventually, a compromise was reached that the men would share the command; Allen would lead the Green Mountain Boys, while Arnold would command the men from Massachusetts and Connecticut. With this settled, Allen and Arnold set about making a plan. A spy named Captain Noah Phelps had already provided Allen with valuable information about Ticonderoga's condition; posing as a fur trapper in need of a haircut and a shave, Phelps had been allowed into Ticonderoga and had taken note of the garrison's weakness and the fort's dilapidated state. Armed with this intelligence, the two commanders decided to surprise the fort with an early morning assault; the Patriots had 250 men and could easily overwhelm the small British garrison.

On the night of 9 May, Arnold, Allen, and 220 of their men marched silently along the Crown Point Road, their movements hidden by the dense forest that surrounded them. At 11 p.m., they arrived at Hand's Cove on the eastern shore of Lake Champlain, less than two miles (3 km) from the fort. Here, they waited while a raiding party of 30 men approached Skenesboro, the nearby estate of Philip Skene, a prominent Loyalist. The plan was for the raiding party to capture the boats at Skenesboro, which would then be used to ferry the men across the lake to the fort. However, upon arriving at Skenesboro, the raiding party took a slight detour into Philip Skene's liquor cellar and proceeded to get drunk; by 1:30 a.m., the main body of troops at Hand's Cove was still anxiously waiting, with no sign of the boats. Finally, close to 3 a.m., the intoxicated raiders returned, but with only two scows, having been unable to locate any more. Each boat could only fit around 40 men, meaning that more than half of the assembled troops would have to be left behind.

Arnold and Allen met to consider the situation. Not only would the attack be going off hours behind schedule, but they would only have 83 men, though they had counted on attacking with all 250. The commanders ultimately decided they did not want to risk losing the element of surprise and opted to go forward with the attack. They loaded 83 of their best men into the scows and sailed off into the lake. The winds were turbulent that morning, causing large waves to constantly crash onto the boats, drenching the men, who did everything they could to prevent capsizing. Shortly after dawn, the boats landed about a half-mile (800 m) from Ticonderoga. Arnold, Allen, and their soaked men disembarked and hurried toward the fort, aware that they needed to make it before the garrison woke up.

The Attack

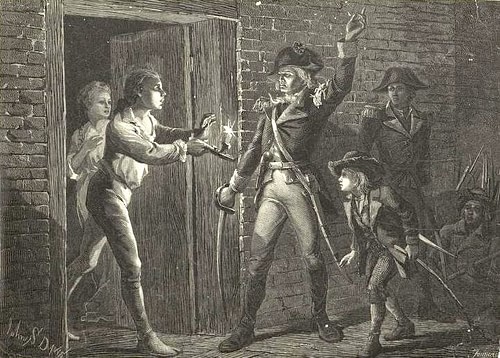

The lone sentry had fallen asleep. It had been a long, wet night, and with no sign of an enemy, he had allowed his eyelids to shut for what he had intended to be only a few moments. Shortly after 4 a.m., the sentry was jostled awake by the sound of several hurried footsteps; peering beyond Ticonderoga's main gate, the guard could just make out the silhouettes of 40 rugged Americans charging straight for him. Startled, the British sentry aimed his musket and pulled the trigger, only to feel a wave of panic as the weapon misfired; the sentry then fled into the fort, running toward the barracks to wake his comrades. Allen and his Green Mountain Boys pursued, easily climbing over the decaying walls of the fort's eastern side and quickly detaining the man.

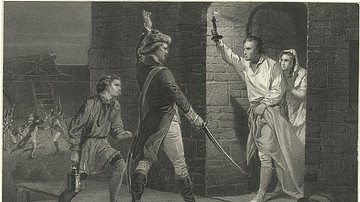

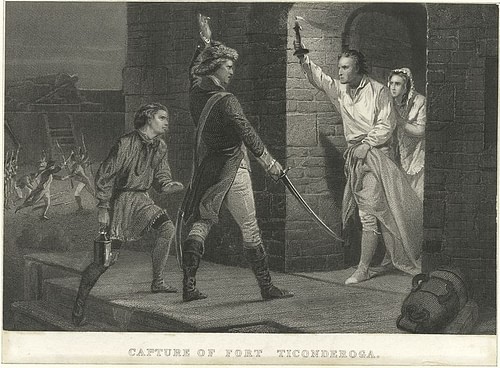

The Green Mountain Boys were then confronted by a second sentry, who fired at the oncoming Patriots but, in his haste, aimed too high and missed. The sentry then lashed out with his bayonet at the nearest American, slightly wounding James Easton, Allen's second in command. Allen then used the flat of his sword to strike the sentry in the side of the head, causing the man to drop his musket. The soldier begged for mercy, which Allen granted him, on the condition that he lead the Patriots to the officers' quarters. By this point, Arnold had entered the fort at the head of the second boatload of men. Most of the Patriots were sent toward the barracks, with orders to each wake up a British soldier at gunpoint and keep him detained. Meanwhile, Allen, Arnold, and six other men followed the captured sentry to the officers' quarters.

Lt. Jocelyn Feltham had been woken up by the commotion and stepped outside; according to Allen's memoirs, Feltham had thrown his officer's jacket over his nightshirt and carried his breeches in his hand. The British lieutenant confronted the Patriots on the staircase that led to the officers' quarters and asked them by whose authority they had dared to enter His Majesty's fort. In response, Allen leveled his saber at Feltham's throat and proclaimed, “in the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress” (Randall, 96). Arnold, who was as diplomatic as Allen was dramatic, presented Feltham with his orders from General Ward and announced that they were taking control of the fort. Allen then went on to threaten that if the British put up any resistance, the entire garrison, including the women and children, would be put to the sword.

After this altercation, the fort's commander, Captain Delaplace, emerged from his quarters and officially surrendered. The Green Mountain Boys then proceeded to plunder the fort, breaking into Delaplace's room and drinking his liquor, despite the captain's protestations. Arnold attempted to stop the plunder, but the Green Mountain Boys still refused to recognize his authority and ignored him. Embarrassed, Allen and Arnold gave Delaplace a receipt for the stolen alcohol which the captain later presented to the Connecticut Committee of Correspondence for reimbursement. But aside from the officers' property, no further damage was done. No one had been killed during the capture of Ticonderoga, and only James Easton, who had been lightly cut by the sentry's bayonet, had been wounded in any way. The 'impregnable' Fort Ticonderoga, the 'Gibraltar of North America', had fallen with no more than a single shot fired.

Aftermath

In the days after Ticonderoga's fall, the Patriots sent detachments to capture other nearby fortifications. Fort Crown Point, which had a garrison of only nine men, fell on 10 May while Fort George, held by only two soldiers, was captured on the 11th. Their mission accomplished, Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys then went home, leaving Ticonderoga and the surrounding forts in the hands of Arnold and his men. When word of the mission's success reached Hartford, the Connecticut Committee dispatched Colonel Benjamin Hinman and 1,400 men to garrison Ticonderoga in the event of a British attack from Canada. But when Hinman arrived, Arnold refused to give up command of the fort, resulting in a leadership struggle between the two men. This dispute continued until 22 June, when the Massachusetts Congress made it clear that Arnold was to serve under Hinman. Arnold felt snubbed, robbed of the spoils of his victory, and resigned. It was the first of several instances in which Arnold felt unappreciated by his countrymen, contributing to his decision to betray the United States five years later.

The capture of Fort Ticonderoga was one of the earliest Patriot victories in the American Revolutionary War. It enraptured the rebels, encouraging many of them to think that they stood a chance against the British. In November 1775, Colonel Henry Knox arrived at Fort Ticonderoga to take the artillery and powder back to Cambridge. He loaded 44 cannons, 14 howitzers, and a mortar onto sleds and transported them the hundreds of miles to Cambridge over difficult winter terrain; Knox's Noble Artillery Train, as it became known, arrived in February 1776. The guns were placed on the heights overlooking Boston, forcing the British to evacuate the city on 17 March. The capture of Ticonderoga, therefore, allowed the Patriots to reclaim Boston and free New England from the presence of British troops.

Ticonderoga's capture also emboldened the Second Continental Congress to order an attack on British-occupied Canada. Using Fort Ticonderoga as a base, the two-pronged American invasion of Quebec began in September 1775, with Benedict Arnold again sharing the command. The invasion was defeated at the Battle of Quebec (31 December 1775), ending American ambitions in Canada. The British briefly recaptured Ticonderoga two years later during their Saratoga Campaign (June to October 1777) but were forced to abandon it shortly thereafter, leaving it permanently in Patriot hands for the remainder of the war.