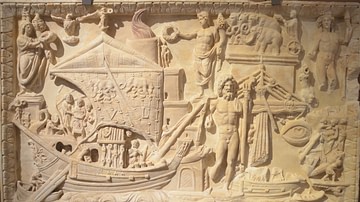

Herod's Harbor was a giant port built between 22 and 15 BCE by Herod the Great (r. 37-4 BCE), Rome's client king. Situated on the lower eastern Mediterranean coast north of Alexandria and south of Tyre, with Rome's largess and building skills, this structure was an engineering feat and visual wonder of its world.

Purpose

As Rome at this time was brought to a stalemate with the empire of Parthia, which controlled the lucrative northern silk routes through Mesopotamia, the harbor's purpose, as it annexed the city of Caesarea Maritima, was not only to control the southern east-west land routes through Arabia and sea routes by way of the Red Sea in particular but also to monopolize eastern Mediterranean trade in general. The location of the harbor, in relation to ship and trade flows, indicates a purposeful plan to capture income. The substantial flow of eastern goods going west to the eastern Mediterranean coast and the general counterclockwise movement of ship traffic in the Mediterranean made the Harbor a gateway to the west.

Goods from India and Indonesia would have moved west, then northwest through the Arabian and Red Seas. Goods from Egypt and Africa would have moved north up the eastern Mediterranean coast for distribution there, then west throughout the Mediterranean. Likewise, as the harbor was en route for emptied or loaded vessels circuiting the Mediterranean and for loaded ships moving north up the coast from Alexandria, the harbor/town complex also interacted with Gaza, which received goods from Africa, Arabia, India, and Indonesia, the most lucrative of which would have been pepper and frankincense.

Foundation

The marvel of Herod's harbor is that it was artificial. In the coastal area where Herod chose to build, there was no significant bay or promontory to build on or to add to. In addition, the biggest hurdle for Herod's builders was the tremendous wind and wave action moving north up the coast. As these same conditions exist today in this area of the Mediterranean, Josephus mentions,

For the case was this, that all the seashore between Dora and Joppa, in the middle, between which this city is situated, had no good haven, insomuch that everyone that sailed from Phoenicia for Egypt was obliged to lie in the stormy sea, by reason of the south winds that threatened them; which wind, if it blew but a little fresh, such vast waves are raised, and dash upon the rocks, that upon their retreat the sea is in a great ferment for a long way. (Wars, 1.21.5)

However, with foundation structures called moles, Herod's harbor ultimately provided a safe haven for ships. These moles were laid out on an interesting circular course to mitigate erosion. Josephus describes the Harbor as a "circular haven" (Antiquities, 15.9.6). Housing around 16 hectares (40 acres) of water, of the two moles, the southern arm extended 300 meters (1000 ft) west out to sea as it curved north 500 meters (1600 ft). The northern breakwater also extended 300 meters (1000 ft) west. Both arms terminated at the harbor's northwestern, 28-meter (60 ft) wide entrance.

Some of the foundation blocks comprising the mole structures weighed up to 50 tons. Josephus mentions one block measuring 15 meters (50 ft) in length, 5.5 meters (18 ft) in width, and 2.75 meters (9 ft) thick (Wars, 1.21.6). However, the use of hydraulic concrete for some of the foundation work is just as remarkable. One scenario is that wooden forms were hauled by boat to the area of placement, which were then, in stages, filled with Roman concrete as they were lowered in place. However, in conjunction with the use of concrete blocks, solid quartz sandstone blocks were also used at the entrance area for the foundation of the southern mole, while formed concrete was used at the northern mole.

Military Superstructure

The foundation of the Harbor would have dealt with hydrodynamic aspects, and its superstructure would have addressed Rome's military concerns. Surmounting the mole's foundation was a superstructure of towers and walls meant to repel any military invasion. Such a complex would have made the harbor appear like a massive fortress at sea.

Josephus mentions "edifices all along the circular haven" and "very large towers on a stone wall that ran around it" (Antiquities, 15.9.6; Wars, 1.21.6). While Josephus fails to give the exact sizes of towers at the harbor, he does give dimensions of Herod the Great's and Herod Agrippa's fortification work at Jerusalem. There, common towers ranged between 9 and 11 meters (30 and 36 ft) square, while curtain wall heights were 9 meters (30 ft), with a typical curtain wall thickness half the wall's height. Common Roman bridge widths were in the 5.5-meter (18 ft) range, and mirroring that workspace makes it possible that the wall width at Herod's Harbor was 5.5 meters (18 ft), supporting an argument for 11-meter (36 ft) square towers. If their height were twice the width, tower-plus-curtain-wall-height at Herod's harbor could have been a whopping 18 or 22 meters (60 or 72 ft). Finally, based on the effective trajectory of arrows shot from composite bows of the day, space between towers would have approached a distance of 27-30 meters (90-100 ft) for adequate crossfire protection. Like at Jerusalem, battlements would have topped all towers and curtain walls.

Additionally, like any fortification, where the entrance is most vulnerable, towers at the entrance to Herod's harbor had to have been definitively outsized, perhaps reaching widths of, 18 meters (60 ft) or more, with dizzying heights reaching over 27 meters (90 ft). That Josephus refers to Drusium as the "principal" tower at the harbor suggests a larger size, as does the fact it was named after a significant person, Caesar's son-in-law, Drusus. Similarly, Herod also assigned people's names to the largest towers in Jerusalem. For comparison, a twin for Drusium would be the tower named Phasaelus, after Herod's brother.

Furthermore, "at the eastern face of the channel leading into the harbor basin" has been found evidence of extraordinary reinforcement (Oleson, 165). The use of blocks fastened together with iron clamps set in lead reveals, as Avner Raban says, "a special function which imposed exceptional physical stress on the structure" (Harbours, part 2, 280). Similarly, Josephus describes the use of lead and iron clamps between blocks at a section of the temple in Jerusalem to secure foundational integrity for a building "which proceeded to a great height" (Antiquities, 15.11.3). The additional effort to produce such foundational support suggests a larger structure, perhaps a lighthouse. Either way, larger towers would have been employed at the Harbor's entrance for defensive measures.

Edifices at the Entrance

The protection of a watery entrance would have required added measures. Josephus relates:

At the mouth of the haven were on each side three great Colossi, supported by pillars, where those Colossi that are on your left hand as you sail into the port, are supported by a solid tower; but those on the right hand are supported by two upright stones joined together. (Wars, 1.21.6)

Supporting Josephus' description of edifices near the entrance, four blocks were discovered approximately 8 meters (26 ft) from a line parallel to the outer face of the northern breakwater. Two blocks, just west of the entrance on entering, corresponds with the structure Josephus describes as joined at the top. The single block discovered just east of the entrance also agrees with Josephus' placement of a solid tower to the left on entering. For function and symmetry, their platform heights would have approximated the curtain wall heights at the harbor. Moreover, these platforms would undoubtedly have served as a height from which to rain down missiles on any hostile vessels attempting a breach at the entrance.

The unusual axis of the two contiguous blocks in relation to the entrance and the breakwaters indicates a deflective hydrodynamic function. As Oleson and Branton state, "They may have been designed to break the force of waves rolling around the barrier of the southern breakwater towards the harbor entrance ... shielding the inner basin from disturbance" (56). Yet this structure would also have produced a redundant eddy effect, which was mitigated by its flow-through feature. Still, the remaining amount of kinetic energy moving past the entrance, as it was pushed toward the shore by ocean pressure and shore-bound waves, would have eddied back toward the entrance.

Of the round tower associated with the block closest to the entrance, Josephus mentions its deflective purpose: "On the left hand, as you enter the port, [there is] a round turret, which was made very strong in order to resist the greatest waves" (Antiquities, 15.9.6). The other structure, located just northeast of the tower block, was likely low-slung (perhaps just under the surface since Josephus missed it in his observations), which would also have deflected energy before it hit the round tower. As angles produced more eddy, the round tower would have produced less. Thus the edifices at the entrance, with their hydrodynamic purpose, would have helped calm the water at the entrance.

Colossi & Temple

As to aesthetics, Josephus mentions that the harbor was ornately finished for its final stage of completion. The most conspicuous aesthetic structure would have been the temple adjoining the harbor and the statues at the entrance as they stood on columns from a lofty height. As Mark Wilson Jones points out, the Corinthian column became the order of choice for the emperors, starting with Caesar Augustus, and "was embraced with surprising rapidity throughout the empire" (139). Additionally, as the fragmentary evidence from debris at Caesarea's temple site suggests Corinthian columns there, the Corinthian was the likely column of choice at the entrance.

Although no remains have been found, since bronze was a durable medium of choice for statues exposed to the elements, especially ocean air, the colossi were probably made of bronze. Finally, while Josephus does not specifically identify who the images were, it is easy to deduce their probable identity from Josephus' statements about the temple and his summary statement about the harbor. Josephus says the temple adjoining the harbor housed the colossi of Caesar and Juno, Rome's patron goddess. Then right after, he states, "So he dedicated the city to the province, and the haven to the sailors there" (Wars, 1.21.7). The third image for the colossi at the harbor's entrance would have been representative of the sea, sailors, and maritime trade, all of which came under the protection of the god Neptune. Thus, the images at the entrance, as they mirrored each other – three on the left and three on the right – were likely of Caesar, Caesarea's namesake; Juno, as a symbolic tribute to Rome; and Neptune, the ultimate protector of maritime trade, which is what the harbor was all about.

The other main ornate feature was the temple. At the foot of the harbor, with its Corinthian columns and cascading steps to the quay, lay the temple through which visiting notables passed. Josephus says the temple could be seen from 'a great way off" and was "excellent both in beauty and largeness" (Antiquities, 15.9.6, Wars, 1.21.7). As vessels approached from the sea, the view of the harbor's ornateness would have started with the temple that could be seen from a distance. Then on closer approach, as intended, Rome's power and level of sophistication would have impressed the minds of all who sailed between the imposing edifices with their towering colossi.

Procumatia

Moving from the entrance to the back of the harbor at the southern mole, though less conspicuous but perhaps the most functional, was the Procumatia. Without it, the harbor would have quickly eroded into rubble, especially, as mentioned, considering the extreme conditions of wind, waves, and currents moving north. Of the structure, Josephus states:

He enlarged that wall which was thus already extant above the sea, till it was two hundred feet wide; one hundred of which had buildings before it, in order to break the force of the waves, whence it was called Procumatia or the first breaker of the waves; but the rest of the space was under a stone wall that ran around it. (Wars, 1.21.6)

Recent material discovery in this area confirms a low-slung structure but freestanding from the mole. As the Procumatia was low-slung, to dissipate the scouring effect of incoming waves and currents more effectively, when Josephus says the Procumatia had "buildings before it, in order to break the force of the waves," this is remindful of today's 'baffle blocks' serving as energy dissipaters at the spillways of dams, reservoirs or other water catchments to reduce downstream erosion.

Causeway

Finally, of functional structures, a causeway at the harbor certainly would have expedited commercial and military activity. As the whole harbor area had been divided into the larger outer harbor and the much smaller inner harbor – where warships carrying commanders and dignitaries of the highest rank would have parked near the temple – dividing the two is a structure identified as a harbor-divide. However, as the moles were virtually separated from each other by the unbridgeable entrance and the adjoining temple, this structure was most likely a causeway spanning the diameter of the harbor as it served several practical purposes.

Commercially, if high traffic made the berthing of an incoming ship intended for one arm unavailable, a vessel could be parked at the other arm while its goods were hauled directly over to the arm intended for offloading. A ship with mixed cargo destined for southern and northern locales could unload completely at one arm without having to be moved. With a causeway, immediate in-place unloading, reloading, and quick dispersal are possible no matter where the initial docking would have been.

Militarily, when it came to the outfitting and manning of the towers and curtain wall, a causeway would have offered a high degree of flexibility. Likewise, in times of war, if the harbor was under assault, a practical diameter course between the two moles would be essential. In the event of an emergency, it would have been impossible for military personnel stationed at one mole to move quickly to the other side.

Conclusion

Met with almost impossible odds against extreme conditions, the master builders of Herod's harbor certainly introduced innovative engineering techniques to accomplish the task. Not only were answers given to unique problems, as the harbor was built on a massive scale expecting to monopolize trade but its size was also equaled by its level of splendor. However, despite its grand view of the future, the harbor's life may have been relatively short.

In 2005, ROMACONS discovered that inferior concrete was used at the site. Whether this compromised the structural integrity of the breakwaters, seismic activity soon caused them to sink. Then a tsunami hit the area sometime in the 1st or 2nd century. These events, along with the constant battering of waves, may have made maintenance impractical for Rome during its own period of decline. By the 6th century, the harbor fell into complete disuse.