Festivals in ancient Mesopotamia honored the patron deity of a city-state or the primary god of the city that controlled a region or empire. The earliest, the Akitu festival, was first observed in Sumer in the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) and continued through the Seleucid Period (312-63 BCE) along with other religious celebrations.

As there was no concept of separation of religion and politics, festivals also served a political purpose in uniting a king's subjects in honoring his god and, in the case of the Akitu festival, legitimizing the king's rule through a public demonstration of the patron god's approval of his reign. Festivals were celebrated throughout the year for several reasons including:

- New Year

- gods' birthdays and incidents from their lives

- ceremonial mourning (such as the rites of the god Tammuz)

- memorable events (such as a military victory)

- sowing and reaping (harvest festivals)

- a monarch's coronation

- birth of royal children

- completion and dedication of a palace, temple, or city

All of these were explicitly or implicitly associated with the patron god of the city or with the Mesopotamian pantheon generally as the gods were understood as the true monarchs and the king as simply their steward. In order to maintain his authority, the king needed to court the goodwill of the gods, and although they made their approval clear through military victories, bountiful harvests, and prosperous trade, events such as the Akitu festival provided an annual opportunity for the divine to continue its relationship with the ruling house or withdraw its favor.

Evidence for the continuance of Mesopotamian festivals becomes sparse after the Seleucid Period, but those of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE) and Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) are thought to have been influenced by them. The Akitu festival is the oldest observance of a New Year's celebration in the world, and other festivals held throughout the year, although little or nothing is known of many of their details, are also thought to have established celebratory traditions later adopted by other civilizations.

The Nature of Mesopotamian Festivals

The gods were understood to have created order out of chaos, providing people with all they needed in their lives and, although human beings were expected to honor them daily by living in accordance with their will, festivals marked days purposefully set aside for giving thanks. Scholar Stephen Bertman explains:

The greatness of the gods and their manifold blessings were celebrated on special holy days and festivals. The most important of these sacred occasions in a community honored its local god, who was its patron and protector. But on a larger scale across their country, the people of Mesopotamia also expressed their gratitude in common for the fertility of their land whose bounty sustained their lives and derived from divine favor. The greatest of these agricultural holidays was called, in Sumerian, the Akiti, and in Akkadian, the Akitu, a word of uncertain meaning that may in fact be pre-Sumerian ... In some communities, like Babylon, the ceremonies were conducted once a year immediately after the barley harvest in March at the time of the spring equinox (barley was Mesopotamia's chief grain). In other communities, like Ur, there were two celebrations a year, one at the time of the harvest and the other in September when new seed was sown. (130)

In the Early Dynastic Period, these festivals were observed independently by each Sumerian city-state in honor of its god, and while this practice was continued during the Akkadian Period (2334-2218 BCE), they were observed throughout Sumer in honor of the divine triad of Akkad, the gods An (Anu), Enlil, and Enki, as well as Ishtar (derived from the Sumerian Inanna). Among the earliest rites were those observed for the dying and reviving god figure, Tammuz, known by scholars today as rituals of ceremonial mourning in which the god dies and returns to life, ensuring fertility and prosperity. These festivals followed the same basic paradigm as those observed earlier by Sumerian kings and served the same purpose: to honor the gods, legitimize the king's rule, and unite the people in religious belief and practice.

Religious Practice in Mesopotamia

The central belief in Mesopotamian religion was that human beings had been created by the gods as co-laborers to maintain the established order. Whatever job one held, one was expected to perform those duties in gratitude and humility, recognizing what was owed to the gods who, by one's labor, were freed to manage their own respective responsibilities. Gula, the goddess of healing, could concentrate her energies on health, Nisaba was free to inspire writing and creativity, Nergal to assure victory in war. Whether one was digging an irrigation ditch or crafting fine jewelry, one was still helping the gods collectively in the maintenance of life on earth.

Among the thousands of deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon were the seven divine powers originally conceived of by the Sumerians:

- Anu

- Enki

- Enlil

- Inanna

- Nanna

- Ninhursag

- Utu-Shamash

Mesopotamian art and architecture honored these seven – and the many others – through depictions of their great deeds as told in the works of Mesopotamian literature and in structures such as temple complexes centered around a towering ziggurat. People did not attend worship services at these temples – one's daily life was supposed to be lived as a kind of devotion – and they were instead regarded as the home of the deity they were dedicated to. The god or goddess was understood as living in the temple in the form of their statue, tended to by the high priest or priestess and lesser clergy, and like any of the humans who served them, they periodically needed a vacation and change of scenery offered by festivals.

During these celebrations, the statue of the deity would be taken from the temple and carried somewhere else – either to another city, around their city, or out of the city to a shrine in the countryside – to give them a holiday just as they were providing to the people. An example of this is given in the Sumerian poem, Shulgi and Ninlil's Barge, dated to the reign of Shulgi of Ur (2029-1982 BCE) in which Shulgi decks out a ship in honor of Enlil and his consort Ninlil and takes them (in the form of their statues), as well as other deities associated with them, downriver from Nippur, the holy city, to the sacred site of Tummal for a banquet.

Akitu & Zagmuk

The most famous festival, however, was the Akitu, which is most clearly documented through its observance in Babylon during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE), at which the god Marduk, and his son Nabu, were honored. Marduk was the patron god of Babylon and Nabu, who had replaced Nisaba as the patron god of writing, was the patron of nearby Borsippa. The Akitu festival absorbed the earlier New Year's festival of Zagmuk, which had been observed for twelve days in December, celebrating Marduk's triumph over Tiamat as given in the Enuma Elish. The Akitu festival also ran for twelve days in honor of the same event but was observed in March. Scholar Christian Roy comments:

Having started out as a sowing and harvest festival, [Akitu] came to prominence in Babylon as the proper occasion for the crowning and investiture of a new king. On this occasion, the reigning monarch's divine mandate was renewed in connection with the sky god Marduk's victory over Tiamat, the goddess of salt water. As a spring festival, Akitu thus bound together the renewal of nature's fertility, the reestablishment of the king's divine authority (formerly a fall ceremony), and the securing of the people's favorable destiny over the coming year – especially the scorching summer heat – while putting an end to the sterility of the winter months when the world seemed old and worn out. (6)

In the Enuma Elish, Tiamat makes war on the younger gods and defeats them in battle repeatedly until they choose Marduk as their leader. As the divine champion of order, Marduk vanquishes the forces of chaos under Tiamat, kills her, and creates the known world. The Akitu festival celebrated this victory while also acknowledging all the gifts of the gods that proceeded from it.

The 12 Days of Akitu

Although the Akitu festival was observed in different cities, sometimes under different names, throughout Mesopotamia's history, the best documented celebration comes from Babylon and so the Babylonian rites are presented below. Preparation for the festival most likely involved a ritual purification of the city, as was done elsewhere, though this is unclear. It is documented, however, that prior to the first day, the statues of gods from other cities were mounted on boats, carts, carriages, or sledges and began their journey toward Babylon to participate in the celebration.

Day One: Marduk's temple complex at Babylon and Nabu's at Borsippa were ornamented and prepared for the celebration.

Day Two: The high priest of Marduk at Babylon dedicated himself to the god through an act of renewal, thanked the god for his gifts, and prayed for his ongoing protection of the city.

Day Three: The high priest of Marduk officiated at a ceremony where two human figures, most likely male and female, were made from wood and represented devotees of Nabu.

Day Four: Prayers were offered to Marduk in Babylon as the king left for Borsippa to accompany the statue of Nabu on its river journey to the city. The high priest made offerings to Marduk and his consort Sarpanitum (also given as Zarpanitum and Sarpanit, among other variations), asking for their blessings, and, in the evening, would recite the Enuma Elish.

Day Five: The high priest would confer with Marduk and Sarpanitum in the temple while the lesser priests cleansed the shrine of Nabu and the central temple complex. Once rituals were complete, the shrine was covered in a canopy of gold, and the people waited in prayer for the return of the king with Nabu's statue and entourage. After the king arrived, the high priest stripped him of his royal robes and insignia and forced him to kneel before the statue of Marduk. The king confessed whatever sins he had committed but swore that he had not abused his authority or forsaken his duties. The priest then slapped the king hard enough to bring tears to his eyes, symbolizing the sincerity of the confession, and the monarch's clothing and insignia were returned to him. Prayers of thanks were then offered to Marduk's and Nabu's planet (Mercury), and Nabu's statue was placed in its shrine.

Day Six: The statues of the gods from other cities arrived and were positioned at intervals between Nabu's shrine and Marduk's temple. The two wooden figures that had been made on Day Three were then offered to Nabu, their heads cut off, and were ritually burned. Bertman suggests this may have been symbolic of earlier human sacrifice (131), but the significance of the act and the figures is unclear.

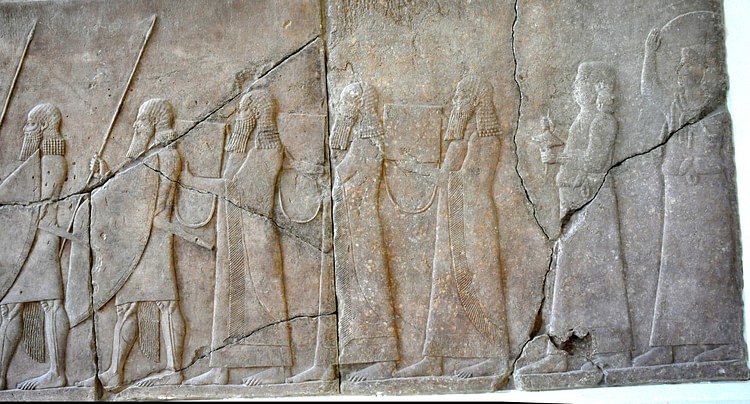

Days Seven and Eight: The ceremonies of these two days seem to blend but, during this time, the king "took the hand" of Marduk, renewing his dedication to serving the god, and ritually led him from his temple into the streets of the city. People followed the statue as the procession – which included the statues of the visiting gods – made its way to the Shrine of Destinies near Nabu's shrine. The priests called on Nabu to give his prophecy regarding the king and the coming year, and, once received, this was recorded. The statues of Marduk, Nabu, and the visiting deities were positioned around the king to honor him, and the "sacred marriage" ritual was enacted to ensure the fertility of the land in the New Year. This rite may have involved the king engaging in sexual intercourse with a priestess of Inanna/Ishtar or a ritual simulation of the act, and, afterwards, Marduk's statue was carried out of the city to his shrine, known as bit-Akitu, located in a large park ornamented with flowers.

Days Nine and Ten: With Marduk situated in his shrine, Nabu in his, and the visiting deities in their respective places of honor, the great feast of Akitu was held over two days. The state provided entertainment, food, and drink for the banquet attended by all the people of the city as well as visitors.

Day Eleven: Marduk's statue was carried back into Babylon to Nabu's shrine, and the statues of the visiting gods were placed nearby. The prophecy of Nabu recorded on Day Seven was read aloud, and afterwards, closing ceremonies were observed.

Day Twelve: The festival concluded with ceremonial rites, and Nabu's statue was taken from his shrine and brought back to the ship he had arrived on to return to Borsippa. After Nabu departed, the statues of the visiting deities and their attendant priests and dignitaries returned to their cities, and the statue of Marduk was placed back in his temple.

Conclusion

Besides the Akitu festival, as noted, there were many other celebrations throughout the year in every era of Mesopotamia's history. Some form of the oldest of these may have been observed in the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE), or earlier, but are first attested in writing from the Early Dynastic Period. The holy city of Nippur, dedicated chiefly to the cult of Enlil, was an important pilgrimage site and host of various celebrations from this era onwards, but festivals were observed in virtually every city throughout Mesopotamia.

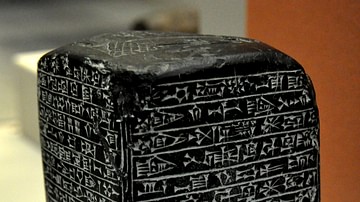

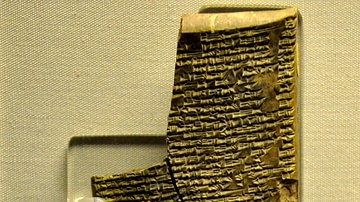

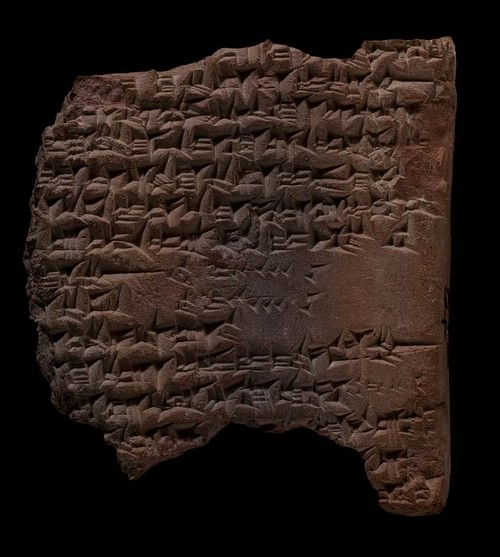

From the Early Dynastic Period through the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) on into the Assyrian Period (c. 1307-912 BCE), Neo-Assyrian Period (912-612 BCE), and further at least through the Seleucid Period, the state sponsored festivals, attested to through inscriptions, stele, reliefs, monuments, and literary works including the Hymn to Inanna, Enlil in the E-kur, and Shulgi and Ninlil's Barge. Among the best documented of the Neo-Assyrian Period is the greatest party ever thrown: Ashurnasirpal II’s Kalhu Festival in 879 BCE to celebrate the completion of the city of Kalhu, attended by 70,000 guests.

Festivals, as noted, served both political and religious purposes but, on an individual level, were the primary means of public, ritual participation in the religious life of the city. As noted, one did not attend religious services weekly or listen to sermons but, instead, served the gods daily through one's actions and offerings brought to the temple complex. Only through festivals was the average person allowed to view the statue of their patron god or take part in a public expression of faith. Scholar A. Leo Oppenheim comments:

The basic function of the temple for the community seems to have been its mere existence in the sense that it linked the city to the deity by providing a permanent dwelling place. The house in which the god lived was maintained and provided for in due form in order to secure for the city the prosperity and happiness which the god's presence was taken to guarantee. Beyond that, the common man was given the opportunity to admire only from afar the glamor of the image displayed in the background of the sanctuary, which he himself was not permitted to enter, at least in Babylonia. Or he was a spectator when the images were carried in processions which displayed the temple's wealth and pomp, and he participated in the collective joys of festivals of thanksgiving and expressions of ceremonial mourning. (108)

Besides serving the interests of the king and state, Mesopotamian festivals met the religious needs of the people by providing them with the opportunity to interact face-to-face with their god. These celebrations were manifestations of the relationship between the people and the divine as they were allowed the chance to personally address and give thanks to the god and, in return, directly receive assurance of blessing, prosperity, and the comfort in knowing that a higher power cared for and would continue to watch over them.