Ghosts in ancient Mesopotamia were understood as a reality of life just as they were in other civilizations of antiquity. Although the cultures of the various Mesopotamian civilizations differed between c. 5000 BCE-651 CE, the belief in ghosts, and responses to supernatural visitations, remained remarkably similar even when funerary rites or visions of the afterlife changed.

The Mesopotamians understood themselves as co-workers with the gods in maintaining order. The gods had created humans out of clay and animated them with a divine breath but set a time limit on each life. When that time was up, each person went to the underworld, known by many names over the centuries but best as Irkalla – the land of no return. The divine aspect of the person lived on in Irkalla, a dark place of dust and puddles, and relied on the living to sustain them through remembrance and sacrifice, especially by daily offerings of cool water.

It was also understood that the body of the deceased required proper burial with all respect including grave goods they would need in Irkalla. If the funerary ritual was not observed correctly, or if the family of the deceased failed to remember them through sacrifice, prayer, and libations, the gods granted the spirit permission to return to the land of the living and haunt those who had forgotten their responsibilities.

This was the most common form of a ghost in Mesopotamia – a family member with a legitimate complaint against the living – but there were also stray ghosts who slipped out of Irkalla without permission or those who died in battle and were left unburied or who drowned, and the body never recovered, and any of these could haunt a home or enter into a person through their ear, bringing sickness, bad luck, or even death.

Modern scholarship has linked the Mesopotamian belief in ghosts to the social structure of the family and importance of the bonds of kinship – and this seems a valid conclusion as one’s duties to the dead forged generational relationships – but to the Mesopotamians themselves ghosts were simply another aspect of life one needed to attend to. If one wanted to remain healthy and enjoy whatever plans one had for the future, the best course was proper care for one’s own departed and measures taken to protect oneself from angry ghosts one had nothing to do with.

Early Belief and Sources

Scholar Irving Finkel has noted that the Mesopotamian belief in ghosts can be dated back to the first burials that included grave goods. The earliest graves excavated in Mesopotamia to date are the nine containing Neanderthal remains at Shanidar Cave in the Zagros Mountains dated to between 60,000 and 45,000 years ago (Black, Gods & Demons, 59). First discovered in 1951, some archaeologists claim the site provides evidence of grave goods in the form of shells and funerary practices evidenced by the presence of flower pollen in the graves, suggesting flowers had been placed on the corpse (though this has been challenged). Grave goods have been positively identified at the site of the ancient city of Eridu, however, dated to c. 5400 BCE. Scholar Gwendolyn Leick comments on grave goods up through the Ubaid Period:

Bodies in earthen or stone graves could be accompanied by sets of tools, such as flint knives, or personal ornaments, such as beads. Traces of red color are also frequently found on bones, indicating some color symbolism. In the Ubaid Period, the graves at Eridu contained rich grave gifts, such as exquisite miniature pottery sets, anthropomorphic clay figurines, joints of meat, and jewelry. Some people had been buried with a dog that was given a bone. (73)

Finkel argues that there is no other reason to place objects of value in a tomb unless one believes the deceased will require them in another realm. Further, if the spirit is able to travel onwards from the mortal world, it is reasonable to assume it could also travel back, as Finkel states in the three points of his argument regarding grave goods and ghosts. Goods are deposited in a grave because of the belief that death is not the end and, therefore, the Mesopotamians believed:

- Something survives of a human being after death.

- That something escapes the grasp of the corpse and goes somewhere.

- That something, if it goes somewhere, can quite reasonably be expected to be capable of coming back. (5)

Finkel accepts the claim that the beads found at Shanidar Caves are, in fact, grave goods and the pollen residue evidence of funerary rites. He comments:

From this vantage point, we should reckon that ghosts arrived on stage by the Upper Paleolithic, perhaps around 50,000 BC. The simple conception that something recognizable of a dead person might at some time return to human society seems to me neither fanciful nor surprising. Its roots originate at that developmental horizon where burial goods became the norm for the first time. In contrast to mourning and burial, it is the deep-seated conception that some part of a person does not vanish forever that separates us absolutely from the whole animal kingdom. (5-6)

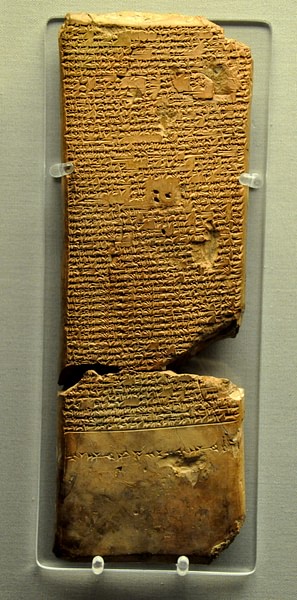

Even if one rejects the earlier date of the Shanidar Cave burials, it is clear the practice of including grave goods in burials was established by the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100) and written sources relating to ghosts appear by the Early Dynastic Period of Mesopotamia (2900-2334 BCE). These include spells to protect one from ghosts, to send a ghost back to the underworld, and spells related to necromancy whereby one could summon a ghost to question it before reciting other spells to return it to where it belonged.

Unlike ancient Egypt which developed a lengthy and intricate collection of works on the afterlife and spirits, Mesopotamian sources are varied and include compositions recited at religious rituals or during funerary rites or famous literary works including Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld, The Epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld, Nergal and Ereshkigal, and The Death of Ur-Nammu.

The Underworld

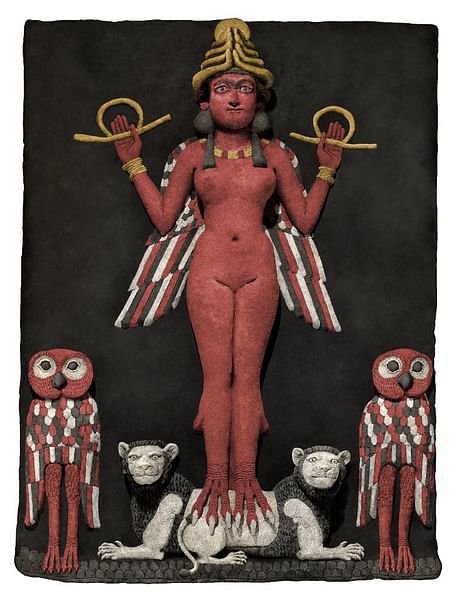

The Mesopotamian underworld was the final destination for all mortals regardless of how they had lived. King or peasant, hero or villain, man, woman, or child, all went to the same place: a dark realm beneath the earth ruled by Ereshkigal, Queen of the Dead who was later joined by her consort Nergal. Ereshkigal was also known as Allatu and Irkalla, also the names of her realm, which also was known as Kurnugia – the Land of No Return. Scholar Jeremy Black comments on the root kur in Kurnugia:

The word kur in Sumerian has two separate meanings. One of these is `mountain’ or, more generally, the `mountains’, especially the Zagros Mountains to the east of Mesopotamia. Because of this, it can also refer to a `foreign land’ (other than Sumer) …the second meaning of kur is `earth, ground’ and in particular kur is one of the names for the world under the ground we live on: the underworld or abode of the dead. (Gods & Demons, 114)

Kurnugia/Irkalla was thought to lie under the Mountains of Sunset in the west early on but eventually there were a number of entrances to the underworld, and it was considered a vast realm that filled with new arrivals constantly every day. Ereshkigal’s central responsibility was to maintain order which included making sure that the dead remained where they belonged, separated from the living, and that no living being entered her realm. She was assisted by her servant Neti, the gatekeeper and, later, by Nergal, god of war.

Ereshkigal is first referenced in a fragment from the Akkadian Period (2334-2218 BCE) but appears fully as Queen of the Dead in the poem The Death of Ur-Nammu from the reign of Shulgi of Ur (2029-1982 BCE). The poem is notable because it presents a different image of the underworld while still retaining the basic vision of a barren land. Kurnugia/Irkalla is always depicted as a desolate wasteland of darkness and dust but, when Ur-Nammu arrives in this poem, a great banquet is held in welcome, and many animals are slaughtered for the feast.

Still, the poet notes, “the food of the underworld is bitter, the water of the underworld is brackish” (lines 83-84; Black, Sumerian Literature, 59). Aside from mention of this banquet, the only departure from a description of a twilight land of dust is the gold and silver table the spirits of stillborn children play at which is laden with honey. It is hardly surprising, then, that spirits would periodically choose to slip out and return to the light of life in the mortal realm.

The Ghosts

As noted, a spirit could return as a ghost – known as a gidim in Sumerian and etemmu in Akkadian – for different reasons. The gidim/etemmu was one’s intelligence, personality, character – the divine spark that separated from the body at death – and this spirit was fully self-aware. At death, it left the body and was guided to the gates of the underworld by the god Ninazu, son of Gula, the goddess of healing and health, who helped the soul transition to death. There was no moral judgment on the soul upon reaching the underworld, only a sort of “check list” consulted to make sure one belonged there. Afterwards, one passed through the seven gates to the realm of darkness as described by Finkel:

All the ghosts are lurking, their numbers increasing every minute as more people die. We’re told in the Akkadian Gilgamesh Epic that “dust is their sustenance, clay their food. They see no light, dwelling in darkness. They are clad like birds, with wings as garments.” One gets the impression of them all swaying with their shoulder together like dusty penguins. The lack of food and drink explains the evolution of a ritual of pouring out drinks and offering food for the dead – it theoretically went down to sustain them in the underworld. (Cawthorne-Finkel Interview, 5)

Some spirits were given leave by Ereshkigal to return to the world above to right a wrong, provide some information regarding their death, or haunt those who had forgotten their obligations, but other ghosts were more or less fugitives from Irkalla. As a completely self-aware spirit, now trapped in a dismal underworld, these spirits wanted to experience life again but, unfortunately for them, their appearance among the living was always unwelcome.

The dead were usually buried under one’s house, in one’s courtyard, or near the home and so the ghost most commonly encountered was the spirit of someone one had known. The most common reason had to do with improper burial rites, ignoring the wishes of the deceased, or forgetting one’s responsibilities in respect and remembrance. The dead who simply rejected their new home, however, could be quite uncomfortable in the underworld and, once they returned to the world above, caused the most trouble.

Protections & Spells

Spells were recited for protection against ghosts, amulets and charms were worn, and small figurines were placed in the home. Among the most popular of these was an image of the demon Pazuzu who, though able to bring drought, famine, and pestilence, was equally adept at preventing them. He was also considered the most effective at warding off evil spirits and ghosts. Pazuzu was also regarded as a defender of humanity against demons, especially the fearsome Lamastu (also Lamashtu) who attacked pregnant women and preyed on infants. Dog amulets and figurines were also regarded as potent protectors as were actual dogs.

Priests could be called upon for assistance with an especially troublesome spirit or the type of physician known as the Asipu, a healer who dealt primarily with the supernatural. The Asipu might recite a spell for protection or teach a person to memorize such a spell, or spells, depending on the type of ghost and the severity of the haunting. An Asipu or priest might also conduct an exorcism if the situation seemed to warrant it or engage in necromancy to speak directly to the ghost and find out what the problem was. Finkel notes:

Babylonian scribes described a whole slew of simple spells and complicated rituals to get rid of ghosts. Some of these rely on lists of all of the different kinds of ghosts – a ghost who died in a fire, say, or a ghost who was run over by a chariot or drowned in a well or died in childbirth. Part of the spell to get rid of them would involve reading out this list, essentially saying: “Whether you are this type of ghost, or that type of ghost, we know who you are. Go back where you belong!” Identification of a troublesome ghost was a means of gaining power over it. (Cawthorne-Finkel Interview, 4)

Animal sacrifice might also be used to appeal to the gods to help drive off a troublesome ghost and, when a wayward ghost was caught, the sun god Shamash, who also presided over justice, would revoke the spirit’s right to any remembrance or devotional obligations in any form and give these to another spirit in Irkalla who had no one to remember them at all.

Conclusion

The spirits considered most blessed in Irkalla were those of people who died with the greatest number of children because it was thought they would have people remember them and observe the rituals of food and drink the longest. The eldest son was tasked with bringing cool water and food offerings to the graves of the departed daily and, after he died, this duty fell to his eldest son. According to some scholars, this belief in the continued relationship of the living to the dead gave rise to a Cult of the Dead. Jeremy Black notes:

It has been suggested that the practice of burial in the prehistoric societies of Mesopotamia sought either to maintain close communication with the deceased, by means of a cult of the dead, or, conversely, to restrain the dead from haunting the living, as they would do if left unburied and free to wander. (Gods & Demons, 58)

Black, among others, notes the cultural benefits of the belief in the continued existence of the soul after death in that it firmly anchored family members in the community where their deceased were buried, connected them to the past, and encouraged continuous obligations which strengthened the family unit, considered central to Mesopotamian society in any era. This is no doubt true but, to an ancient Mesopotamian, a belief in life after death and the very real possibility of a ghost appearing in one’s home was just part of the natural course of life and to be expected as easily as rain from a threatening sky.