Ereshkigal (also known as Irkalla and Allatu) is the Mesopotamian Queen of the Dead who rules the underworld. Her name translates as 'Queen of the Great Below' or 'Lady of the Great Place.' She was responsible for both keeping the dead within her realm and preventing the living from entering and learning the truth of the afterlife.

The word great as applied to her realm should be understood as vast, not exceptional and referred to the land of the dead which was thought to lie beneath the Mountains of Sunset to the west and was known as Kurnugia ('the Land of No Return') or as Irkalla or Allatu after its queen. Kurnugia was an immense realm of gloom under the earth, where the souls of the dead drank from muddy puddles and ate dust.

Ereshkigal ruled over these souls from her palace Ganzir, located at the entrance to the underworld, and guarded by seven gates which were kept by her faithful servant Neti. She ruled her realm alone until the war god Nergal (also known as Erra) became her consort and co-ruler for six months of the year.

Erishkigal is the older sister of the goddess Inanna and best known for the part she plays in the famous Sumerian poem The Descent of Inanna (c. 1900-1600 BCE). Her first husband (and father of the god Ninazu) was the Great Bull of Heaven, Gugalana, who was killed by the hero Enkidu in The Epic of Gilgamesh.

Her second husband (or consort) was the god Enlil with whom she bore a son, Namtar, and by another consort her daughter Nungal (also known as Manungal) was conceived, an underworld deity who punished the wicked and was associated with healing and retribution. Her fourth consort was Nergal, the only mate who agreed to remain with her in the realm of the dead.

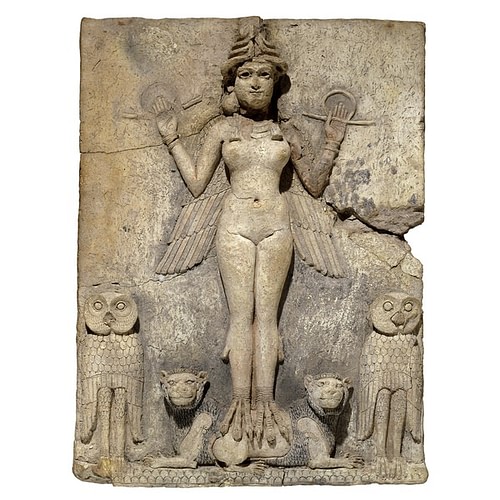

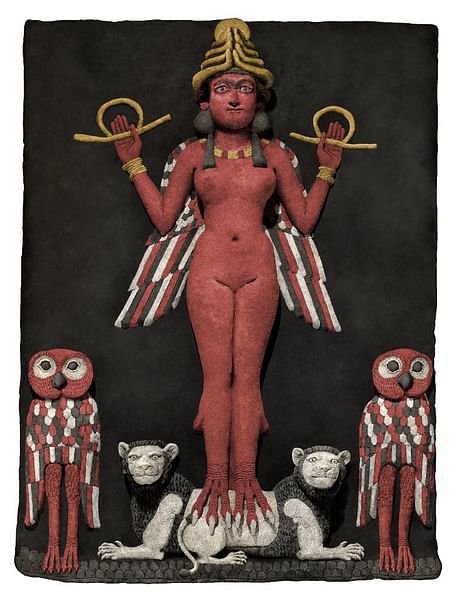

There is no known iconography for Ereshkigal or, at least, none universally agreed on. The Burney Relief (also known as The Queen of the Night, dating from Hammurabi's reign of 1792-1750 BCE) is often interpreted as representing Ereshkigal. The terracotta relief depicts a naked woman with downward-pointing wings standing on the backs of two lions and flanked by owls. She holds symbols of power and, beneath the lions, are images of mountains. This iconography strongly suggests a depiction of Ereshkigal but scholars have also interpreted the work as honoring Inanna or the demon Lilith.

Although the relief most likely does depict Ereshkigal, and there are other similar reliefs of this same figure with varying details, it would not be surprising to find few images of her in art. Ereshkigal was the most feared deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon because she represented one's final destination from which there was no returning.

In Mesopotamian belief, to create an image of someone or something was to invite the attention of the subject. Statues of the gods were thought to house the gods themselves, for example, and images on people's cylinder seals were thought to have amuletic properties. A statue or image of Ereshkigal, then, would have directed the attention of the Queen of the Dead to the creator or owner, and this was far from desirable.

Early Mention & Popularity

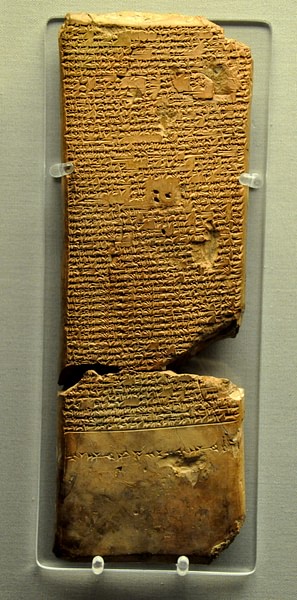

Ereshkigal is first mentioned in the Sumerian poem The Death of Ur-Nammu which dates to the reign of Shulgi of Ur (2029-1982 BCE). She was undoubtedly known earlier, however, and most likely during the Akkadian Period (2334-2218 BCE). Her Akkadian name, Allatu, may be referenced on fragments predating Shulgi's reign.

By the time of the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) Ereshkigal was widely recognized as the Queen of the Dead, lending support to the claim that the Queen of the Night relief from Hammurabi's reign depicts her. Although goddesses lost their status later in Mesopotamian history, early evidence clearly shows the most powerful deities were once female.

Inanna (later Ishtar of the Assyrians) was among the most popular deities and may have inspired similar goddesses in many other cultures including Sauska of the Hittites, Astarte of the Phoenicians, Aphrodite of the Greeks, Venus of the Romans, and perhaps even Isis of the Egyptians. The underworld in all these other cultures was ruled by a god, however, and Ereshkigal is unique in being the only female deity to hold this position even after gods supplanted goddesses and Nergal was given to her as consort.

Ereshkigal in The Descent of Inanna

Although Ereshkigal was feared, she was also greatly respected. The Descent of Inanna has been widely - and wrongly - interpreted in the modern day as a symbolic journey of a woman becoming her 'true self.' Written works may be interpreted in any reasonable way only insofar as that interpretation can be supported by the text. The Descent of Inanna certainly lends itself to a Jungian interpretation of a journey to wholeness by confronting one's darker half, but this would not have been the original meaning of the poem nor is that interpretation supported by the work itself. Far from praising Inanna, or presenting her as some heroic archetype, the poem shows her as selfish and self-serving and, further, ends with praise for Ereshkigal, not Inanna.

Inanna/Ishtar is frequently depicted in Mesopotamian literature as a woman who largely thinks only of herself and her own desires, often at the expense of others. In The Epic of Gilgamesh, her sexual advances are spurned by the hero and so she sends her sister's husband, Gugulana, The Bull of Heaven, to destroy Gilgamesh's realm. After hundreds of people are killed by the bull's rampage, it is killed by Enkidu, the friend and comrade-in-arms of Gilgamesh. Enkidu is condemned by the gods for killing a deity and sentenced to die; the event which then sends Gilgamesh on his quest for immortality. In the Gilgamesh story, Inanna/Ishtar only thinks of herself and the same is true in The Descent of Inanna.

The work begins by stating how Inanna chooses to travel to the underworld to attend Gugulana's funeral - a death she brought about - and details how she is treated when she arrives. Ereshkigal is not happy to hear her sister is at the gates and instructs Neti to make her remove various articles of clothing and ornaments at each of the seven gates before admitting her to the throne room. By the time Inanna stands before Ereshkigal she is naked, and after the Annuna of the Dead pass judgment against her, Ereshkigal kills her sister and hangs her corpse on the wall.

It is only through Inanna's cleverness in previously instructing her servant Ninshubur what to do, and Ninshubur's ability to persuade the gods in favor of her mistress, that Inanna is resurrected. Even so, Inanna's consort Dumuzi and his sister (agricultural dying and reviving deities) then need to take her place in the underworld because it is the land of no return and no soul can come back without finding a replacement.

The main character of the piece is not Inanna but Ereshkigal. The queen acts on the judgment of her advisors, the Annuna, who recognize that Inanna is guilty of causing Gugulana's death. The text reads:

The annuna, the judges of the underworld, surrounded her

They passed judgment against her.

Then Ereshkigal fastened on Inanna the eye of death

She spoke against her the word of wrath

She uttered against her the cry of guilt

She struck her.

Inanna was turned into a corpse

A piece of rotting meat

And was hung from a hook on the wall.

(Wolkstein and Kramer, 60)

Inanna is judged and executed for her crime, but she has obviously foreseen this possibility and left instructions with her servant Ninshubur. After three days and three nights waiting for Inanna, Ninshubur follows the commands of the goddess, goes to Inanna's father-god Enki for help, and receives two galla (androgynous demons) to help her in returning Inanna to the earth. The galla enter the underworld "like flies" and, following Enki's specific instructions, attach themselves closely to Ereshkigal. The Queen of the Dead is seen in distress:

No linen was spread over her body

Her breasts were uncovered

Her hair swirled around her head like leeks.

(Wolkstein and Kramer, 63-66)

The poem continues to describe the queen experiencing the pains of labor. The galla sympathize with the queen's pains, and she, in gratitude, offers them whatever gift they ask for. As ordered by Enki, the galla respond, "We wish only the corpse that hangs from the hook on the wall" (Wolkstein and Kramer, 67) and Ereshkigal gives it to them. The galla revive Inanna with the food and water of life, and she rises from the dead.

It is at this point, after Inanna leaves and is given back all that Neti took from her at the seven gates, that someone else must be found to take Inanna's place. Her husband Dumuzi is chosen by Inanna and his sister Geshtinanna volunteers to go with him; Dumuzi will remain in the underworld for six months and Geshtinanna for the other six while Inanna, who caused all the problems in the first place, goes on to do as she pleases.

The Descent of Inanna would have resonated with an ancient audience in the same way it does today if one understands who the central character actually is. The poem ends with the lines:

Holy Ereshkigal! Great is your renown!

Holy Ereshkigal! I sing your praises!

(Wolkstein and Kramer, 89)

Ereshkigal is chosen as the main character of the work because of her position as the formidable Queen of the Dead, and the message of the poem relates to injustice: if a goddess as powerful as Ereshkigal can be denied justice and endure the sting then so can anyone reading or hearing the poem recited.

Ereshkigal & Nergal

Ereshkigal reigns over her kingdom alone until the war god Nergal becomes her consort. In one version of the story, Nergal is seduced by the queen when he visits the underworld, leaves her after seven days of love-making, but then returns to stay with her for six months of the year. Versions of the story have been found in Egypt (among the Amarna Letters) dating to the 15th century BCE and at Sultantepe, site of an ancient Assyrian city, dated to the 7th century BCE; but the best-known version, dating from the Neo-Babylonian Period (c. 626-539 BCE), has Enki manipulating the events which send Nergal to the underworld as consort to the Queen of the Dead.

One day the gods prepared a great banquet to which everyone was invited. Ereshkigal could not attend, however, because she could not leave the underworld and the gods could not descend to hold their banquet there because they would afterwards be unable to leave. The god Enki sent a message to Ereshkigal to send a servant who could bring her back her share of the feast, and she sent her son Namtar.

When Namtar arrived at the gods' banquet hall, they all stood out of respect for his mother except for the war god Nergal. Namtar was insulted and wanted the wrong redressed, but Enki told him to simply return to the underworld and tell his mother what happened. When Ereshkigal hears of the disrespect of Nergal, she tells Namtar to send a message back to Enki demanding that Nergal be sent so she could kill him.

The gods confer on this request and recognize its legitimacy and so Nergal is told he must journey to the underworld. Enki has understood this would happen, of course, and provides Nergal with 14 demon escorts to assist him at each of the seven gates of the underworld. When Nergal arrives, his presence is announced by Neti, and Namtar tells his mother that the god who would not rise has come. Ereshkigal gives orders that he is to be admitted through each of the seven gates which should then be barred behind him and she will kill him when he reaches the throne room.

After passing through each gate, however, Nergal posts two of his demon escorts to keep it open and marches to the throne room where he overpowers Namtar and drags Ereshkigal to the floor. He raises his great axe to cut off her head, but she pleads with him to spare her, promising to be his wife if he agrees and share her power with him. Nergal consents and seems to feel sorry for what he has done. The poem ends with the two kissing and the promise that they will remain together.

Since Nergal was often causing problems on earth by losing his temper and causing war and strife, it has been suggested that Enki arranged the entire scenario to get him out of the way. War was recognized as a part of the human experience, however, and so Nergal could not remain in the underworld permanently but had to return to the surface for six months out of the year. Since he had posted his demon escorts at the gates, had arrived of his own free will, and been invited to stay as consort by the queen, Nergal was able to leave without having to find a replacement.

As in The Descent of Inanna, the symbolism of The Marriage of Ereshkigal and Nergal (either version) touches on the same themes as the Greek story of the Demeter, goddess of nature and bounty, and her daughter Persephone who is abducted by Hades. In the Greek tale, having eaten of the fruit of the dead, Persephone must spend half a year in the underworld with Hades and, during this time, Demeter mourned the loss of her daughter.

This story explained the seasons in that when Demeter and Persephone were together, the world was in bloom, but when Persephone returned to the underworld, nothing would grow and the earth was cold. The Descent of Inanna corresponds directly while The Marriage of Ereshkigal and Nergal explains the seasons of war since conflicts were waged only in certain seasons.

Ereshkigal's Significance

Ereshkigal is always represented in prayers and rituals as a formidable goddess of great power but often in stories as one who forgives an injustice or a wrong in the interests of the greater good. In this role, she encouraged piety in the people who should follow her example in their own lives. If Ereshkigal could suffer injustice and continue to perform her tasks in accordance with the will of the gods, then human beings should do no less.

Her further significance was as the ruler of the underworld by which she was understood to reward the good and punish the evil, of course, but more importantly to keep the dead in the realm where they belonged. The seven gates of the underworld were constructed both to keep the living out and to keep everyone who belonged there in.

A cult of the dead grew up around Ereshkigal to honor those who had passed into her realm and continue to remember and care for them. Since the dead had nothing but muddy water to drink and dust to eat, food was placed and fresh water poured on tombs, which was thought to trickle down to the mouth of the departed. Scholar E. A. Wallis Budge writes:

The tears of the living comforted the dead and their lamentations and dirges consoled them. To satisfy the cravings of the dead these offerings were sometimes made by priests who devoted their lives to the cult of the dead, and the kinsmen of the dead often employed them to recite incantations that would have the effect of bettering the lot of the dead in the dread kingdom of Ereshkigal...The chief object of all such pious acts was to benefit the dead but underneath it all was the fervent desire of the living to keep the dead in the underworld. The living were afraid lest the dead should return to this world and it was necessary to avoid such a calamity at all costs. (145)

Ereshkigal, as with all the gods of Mesopotamia, maintained order and stood against the forces of chaos. Those souls who had left the world of the living were not supposed to return, and Ereshkigal made certain they remained where they belonged. If a ghost should come back to haunt the living, unless it was a restless fugitive who had managed to slip out of Irkalla, one could be sure it was for a good reason and with Ereshkigal's permission.

As in other cultures, the main reasons for a haunting were improper burial of the dead, neglect of daily rituals of remembrance, or impious acts which had gone unpunished. As queen and guardian of the dead, Ereshkigal stood as a potent reminder to the living to observe the proper rites and rituals in their lives and to act in the best interests of their immediate and larger communities.