The medieval indulgence was a writ offered by the Church, for money, guaranteeing the remission of sin, and its abuse was the spark that inspired Martin Luther's 95 Theses. Luther (l. 1483-1546) claimed the sale of indulgences was unbiblical, challenging the authority of the Church and its claim as God's earthly representative.

Indulgences were nothing new and were based on the concept of the 'treasury of the Church', which held that the merits of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the saints, and others who had led exemplary lives, could be drawn on by laypersons to lessen their time – or that of a loved one – in purgatory or remit the penalty of sin in this life. Initially, sale of an indulgence carried with it the expectation that the buyer would perform penitential acts but, by Martin Luther's time, paying money for the writ was frequently considered enough.

Luther objected to this practice in sermons prior to 1517, but when the indulgence-seller Johann Tetzel (l.c. 1465-1519) arrived in his region in 1516, Luther composed his 95 Theses – disputations on indulgences – and posted them for scholarly debate. His supporters translated the document from Latin to German and published it at the same time as Albrecht von Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, to whom Luther had sent a copy, passed it on to Pope Leo X. These two events turned Luther's 95 topics for debate into direct challenges to the authority of the Church which, in trying to silence Luther, only radicalized him, leading to the Protestant Reformation.

Indulgences Pre-1400

The earliest form of the indulgence appears after the reign of the Roman emperor Decius (249-251) who, in persecuting Christians, demanded a writ of proof that they had sacrificed to the Roman gods. Christians who did so had to deny their faith and, afterwards, when they sought readmittance, were refused for so doing. Some of these 'fallen ones' then produced a writ attributed to a martyr or a well-respected deceased church member, vouchsafing their faith in Christ, and were taken back into the fold. This is considered the earliest indulgence as it formed the policy of leniency, which was the core of the later writs.

Although there does not seem to have been any development of the theology behind the indulgence at this time, the acceptance of the writ suggests that it conferred on the 'fallen' the spiritual merits, acquired in abundance and no longer needed, of the martyr. The 'fallen' still needed to do penance, but the writ assured the early Church that the person was worthy of readmittance. Scholar John Bossy writes:

The institution had its origins in the earlier regime of public penance, and the term applied to the remission, diminution, or conversion of the penal satisfaction imposed on the sinner in the course of his readmission to the community of the Church. It also covered the undertaking by the Church to offer its prayers or suffragia to God that he would likewise be reconciled. (54)

The indulgence (meaning "to be kind to" or "indulgent of") was understood as proof of God's willingness to forgive since someone of great spiritual merit had vouched for the sinner. This understanding led to the development of the concept of the 'treasury of merit' (also known as the 'treasury of the Church') which held that a certain amount of spiritual merit, built up by the selfless acts of Christ, the Virgin Mary, the saints, and the martyrs, could be drawn upon by those in need for their own salvation.

The sinner still had to prove worthy of forgiveness, however, by performing penitential acts. Which acts imposed were up to one's priest who heard one's confession, and in some cases, one's sins might require acts one simply was not capable of due to one's age, health, or social responsibilities, and so a fine was imposed and this money used for charitable causes such as the building and maintenance of churches, sick-houses, orphanages, and similar institutions.

In 1095, Pope Urban II declared indulgences for anyone taking part in the First Crusade (1095-1102). By performing this act, one was absolved of all sin, but those who could not participate could pay a certain sum for an indulgence instead. Saint Albertus Magnus (l. c. 1200-1280) and Church Father Thomas Aquinas (l. 1225-1274) developed the concept of the treasury of merit further and so justified the indulgence as the physical manifestation of a spiritual transaction in which one received a surplus of spiritual 'points' in return for penitential acts which, otherwise, might not be worth as much.

Indulgences Post-1400

The policy concerning indulgences gradually changed, however, as their sale began to contribute more significantly to the revenues of the medieval Church. Congregants noted that some people were allowed to simply pay for the remission of sins and bypass penance. Pardoners (an office of the Church dedicated to the sale of indulgences) roamed city to city performing elaborate sermons designed to scare people into purchasing indulgences for themselves or loved ones suffering for their sins in purgatory. Bossy notes:

By 1400, [indulgences] had become attached to a variety of works, of which the most important was the crusade, but including public improvements like bridge or church-building; it had become established that these works could be performed by proxy, or commuted for money; the granting of it had become in effect a papal monopoly; and in answer to the objection that sins could not be forgiven for which satisfaction had not been made, theologians like Aquinas had come up with the notion of the treasure of the Church. ... Satisfactory penance due from one person could be made by another, provided the relation between the two parties was sufficiently intimate that what was done by one of them could be taken, by God and by the Church, as being done by the other. (54)

The Church could accept one's penitential acts or one could pay a certain amount of money in penance, which allowed one access to the treasury of merit (treasure of the Church). That merit could be applied to oneself in this life, banked for oneself in the next to shorten one's stay in purgatory or, for the right amount, bypass purgatory entirely, or be applied to one's family and friends already thought to be suffering in penitential fires in the realm between hell and heaven.

Although the Church officially denounced unscrupulous pardoners (such as the one who appears in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales) and other indulgence salesmen, it continued to profit from their work, as did the nobility who allowed the sales in their realms. Documents sent on to Rome were often altered to show fewer indulgences sold, and half, or more than half, of the proceeds went to the regional noble.

Indulgence Sales & Johann Tetzel

Church policy of accepting monetary payment without penitential acts continued as the writs became more popular and as salesmen came to be seen by the people as entertainment coupled with the promise of salvation. Believers gladly handed over their money to the salesmen who promised instant results in catchphrases like the popular, "When the gold in the coffer rings, the rescued soul toward heaven springs" (also given as "When the money in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs"). People were eager to pay for indulgences and excited for the kind of 'fire and brimstone' exhibitions the indulgence salesmen brought to town. Scholar Lyndal Roper comments:

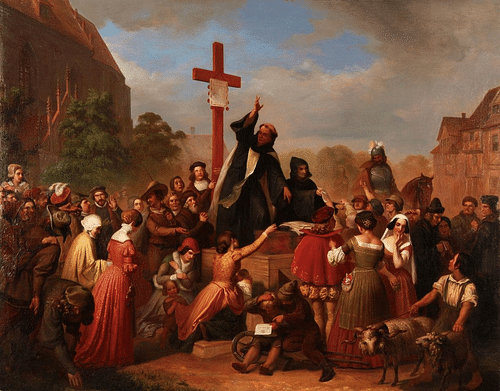

No one compelled people to buy indulgences, but there was a huge market for them. When the indulgence-sellers arrived at a town the papal bull [the charter approving the indulgence, with the Pope's lead seal affixed] would be carried about on a satin or golden cloth, and all the priests, monks, town council, schoolmaster, schoolboys, men, women, maidens, and children, all met it singing in procession with flags and candles. All the bells were rung, all the organs were played…the indulgence-seller was led into the churches and a red cross was erected in the middle of the church where the papal banner would be hung. So efficiently organized was the system that the indulgences were even printed locally on parchment that could be filled in with the name of the person on whose behalf they were purchased. (xx-xxi)

In 1516, the archbishop of Mainz, Albrecht von Brandenburg, received approval from Pope Leo X to sell indulgences in his region. Albrecht was heavily in debt to the Fugger banking family, who had financed the purchase of his ecclesiastical office, and, at the same time, he had promised a significant sum to Rome to help build Saint Peter's Basilica. Pope Leo X also required a large influx of cash for St. Peter's as the old building had fallen into near ruin, and he hoped his legacy would be a grand new structure. The two agreed to split whatever profits came from the sales between them.

One of the most effective indulgence salesmen, Johann Tetzel, was sent to the region and began his usual performances, which often involved pyrotechnic displays simulating the fires of purgatory one could pay to avoid, for the crowds that gathered. Tetzel is often credited with coining the catchphrase about the coffer and coin, but it seems it existed before his time. If he did not coin it, he certainly seems to have used it to full effect. Martin Luther, a professor at the University of Wittenberg, had been critical of indulgences in his sermons earlier, but now with Tetzel close at hand, he felt he needed to engage his fellow theologians and clergy in a debate on the efficacy and morality of indulgence sales.

Luther's Attack on Indulgences

On 31 October 1517, according to the traditional account, Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg. He chose this date, All Saints' Eve, because the city's church would open on All Saints' Day for the viewing of relics and sale of indulgences. After posting them, he sent a copy to Albrecht von Brandenburg, knowing nothing of the archbishop's deal with the pope. The theses, written in Latin, were a common practice to invite debate and were never intended to be any more than this.

When Albrecht von Brandenburg finally received the theses, he had them checked for heresy and then sent on to Rome, elevating them to the status of an official matter for the Church. At the same time, in early 1518, Luther's supporters translated the theses into German and published them, presenting to the general public what clearly seemed to be ninety-five challenges to papal authority and the policies of the Church. Luther's stand on indulgences is clarified throughout the theses and in his later attack on them:

Indulgences are positively harmful to the recipient because they impede salvation by diverting charity and inducing a false sense of security. Christians should be taught that he who gives to the poor is better than he who receives a pardon. He who spends his money for indulgences instead of relieving want receives not the indulgence of the pope but the indignation of God…Indulgences are most pernicious because they induce complacency and thereby imperil salvation. Those persons are damned who think that letters of indulgence make them certain of salvation. (Bainton, 69)

At first, Luther only wanted an open debate on the topic of indulgences and true penance, but when his theses became a popular rallying point for the peasantry against the status quo and were also embraced by Luther's immediate sovereign, Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525), the Church tried to silence him, and Luther responded by questioning the entire hierarchy, vision, and legitimacy of the Church. Roper comments:

By attacking the understanding of penance, Luther was implicitly striking at the heart of the papal Church, and its entire financial and social edifice, which worked on a system of collective salvation that allowed people to pray for others and so reduce their time in purgatory. It financed a whole clerical proletariat of priests paid to recite anniversary Masses for the souls of the deceased. It paid for pious laywomen in poorhouses who said prayers for the souls of the dead, to ease their path through purgatory. It paid for brotherhoods that prayed for their members, said Masses, undertook processions, and financed special altars. In short, the system structured the religious and social lives of most medieval Christians. At its center was the Pope, who was the steward of the treasury of "merits" – grace that could be distributed to others. Attacking indulgences, therefore, would sooner or later lead to a questioning of papal power. (xx)

This is precisely what happened, and events moved quickly between 1518-1521, during which time Luther struck directly at papal authority and was excommunicated. At the Diet of Worms in 1521, he was told to recant or be branded a heretic and outlaw. Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms, or as it came to be known his "Here I Stand" speech, explained his position eloquently; he stood his grounds. He would no doubt have been arrested and executed afterwards but was secretly given protection by Frederick III at his castle in Wartburg.

Conclusion

Once at Wartburg, Luther was free to compose more detailed and powerful objections to church policy as well as translate the New Testament from Latin into German – in defiance of the Church's prohibition on this. Luther's insistence on the primacy of faith and the scripture undermined the Church's claim to be the sole representative of God on earth. Instead, Luther claimed, the Church and its pope were anti-Christ, a stumbling block to believers, who maintained their pretense of being ordained by God by threatening Christians with afterlife torments in hell and purgatory. Indulgences, Luther claimed, were one of the more effective means by which they did so. Scholar Roland H. Bainton comments on how the Church used indulgences to maintain power over the people:

The explanation lies in the tensions which medieval religion deliberately induced, playing alternately upon fear and hope. Hell was stoked, not because men lived in perpetual dread, but precisely because they did not, and in order to instill enough fear to drive them to the sacraments of the Church. If they were petrified with terror, purgatory was introduced by way of mitigation as an intermediate place where those not bad enough for hell nor good enough for heaven might make further expiation. If this alleviation inspired complacency, the temperature was advanced on purgatory, and then the pressure was again relaxed through indulgences. (12)

The Church's refusal to accept Luther's criticism led, first, to the Reformation in Germany and then in other nations as Luther's challenges inspired others to do the same as he had. In Switzerland, Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) was directly influenced by Luther, as John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) would be in France. Once the Church's authority was no longer absolute, reformers began to appear in different regions and countries throughout Europe, establishing their own visions of Christianity and how best to interpret the scriptures.

The Church finally did respond to Luther's reproach and the movement he incited with the so-called Counter-Reformation (1545-c. 1700), during which abuses were rectified and policies reformed, including the moderation and reevaluation of indulgences. Indulgences are still issued by the Catholic Church in the present day but are understood as granting only the relief of temporal punishment for one's sins, not release from purgatory for oneself or another.

Had the Church modified its policy prior to 1517, the Protestant Reformation may never have occurred or, at least, not in the way or at the time that it did. As it was, however, the Church understood itself and was understood by adherents as the only path to eternal life and salvation from the fires of hell. As God's representative and interpreter, the Church could not conceive of crediting the objections of a provincial priest with any merit and seem to have thought he could be silenced as dissenters before him had been. As they soon discovered, they were wrong, and the power of the Holy Roman and Apostolic Church was broken.