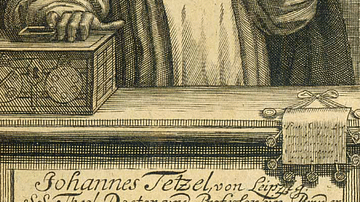

Johann Tetzel (l.c. 1465-1519) was a Dominican Friar who became famous as one of the most effective indulgence salesmen and who inadvertently inspired the Protestant Reformation when Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) wrote his 95 Theses protesting the sale of indulgences generally and Tetzel’s methods specifically, thereby challenging the authority of the Catholic Church.

Tetzel was a popular preacher early in his career and respected highly enough to receive notice from the pope. In c. 1516, Pope Leo X needed money to help rebuild St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and pushed the sale of indulgences as a means to this end. Indulgences – writs purchased for the forgiveness of sins for oneself or another to lessen time in purgatory - had once been handwritten slips before the printing press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg (l.c. 1398-1468), allowed for mass production of printed material. One of the first writs produced by Gutenberg was indulgences for the Church which were then sold in greater volume than before.

In 1516, the archbishop of Mainz, Albrecht con Brandenburg, asked Leo X for dispensation to sell indulgences in his region and the pope sent Tetzel with his mass-produced stack of the writs. Martin Luther was already disturbed by the practice of selling indulgences as it was not supported by the Bible but now the thought of Tetzel operating in Luther’s home region became intolerable. According to the traditional account, on 31 October 1517, Luther nailed his 95 Theses condemning the sale of indulgences to the church door in Wittenberg and so began the Protestant Reformation.

The Church at first supported Tetzel and demonized Luther but, as support for Luther grew in 1518, Tetzel was criticized for his methods and condemned. He retired to a Dominican monastery in Leipzig in broken health and died there in 1519. Luther made peace with him before his death but his reputation had been destroyed after the 95 Theses and he was remembered, not for his earlier preaching, but for the couplet attributed to him as a salesman: “When the gold in the casket rings/The rescued soul toward heaven springs.”

Early Life & Preaching

Johann Tetzel was born in Pirna, Saxony and that is all that is known of his life until he is enrolled at the University of Leipzig in 1482. He was awarded his bachelor’s degree in theology in 1487, ranking sixth in a class of fifty-six. After graduation, he entered the Dominican Order and took up residence at the monastery at Leipzig. He came into conflict with some of the other monks there (the details are lost) and left for Rome in 1497 to request permission to move to another monastery. How his request was answered is unknown and he next appears preaching in the Polish provinces where he was appointed Inquisitor by Cardinal Thomas Cajetan (l. c. 1468-1534). He seems to have made a name for himself as an effective preacher and defender of the faith before moving back to Leipzig and accepting the position of Inquisitor in Saxony.

The first record of Tetzel as a preacher of indulgences and salesman is in 1503 and, by 1509, he was the indulgence commissary in Strasbourg. In this position, he traveled throughout the region, arriving with great fanfare in towns and cities, preaching powerful sermons to crowds on the merits of indulgences and encouraging their purchase. These sermons often emphasized the suffering of those in purgatory and the small sacrifice asked of the living to provide them comfort and help them move on toward heaven. Scholar Carter Lindberg includes a sample sermon by Tetzel in his work in which the preacher plays on the fear and guilt of his audience:

Behold, you are on the raging sea of this world in storm and danger, not knowing if you will safely reach the harbor of salvation…You should know that all who confess and in penance put alms into the coffer will obtain complete remission of all their sins. Why are you then standing there? Run for the salvation of your souls!

Don’t you hear the voices of your wailing dead parents and others who say, “Have mercy upon me, have mercy upon me, because we are in severe punishment and pain. From this you could redeem us with small alms and yet you do not want to do so.”

Open your ears as the father says to the son and the mother to the daughter, “We have created you, fed you, cared for you, and left you our temporal goods. Why then are you so cruel and harsh that you do not want to save us, though it only takes so little? You let us lie in flames so that we only slowly come to the promised glory.” You may have letters which let you have, once in life and in the hour of death, full remission of the punishment which belongs to sin… (Source 2.7; p. 28)

The indulgence was never originally intended to be any kind of scam or money-making venture and, according to some scholars, Tetzel was only preaching Church doctrine regarding a penitent believer’s willingness to make amends for some wrongdoing. The indulgence was not a “get out of sin free” card but a writ assuring one of forgiveness of sin if one was truly sorry and would do penance. This initial understanding of the indulgence seems to have changed by c. 1500, however.

Indulgences

An indulgence (meaning “to be indulgent of” or “kind to” a sinner) was originally a sort of “letter of recommendation” – someone of spiritual merit was vouching for another who had fallen short of their commitment to Christ and His Church. The idea was that there existed a `treasury of merit’ (also known as the ‘treasury of the Church’) built up by the sacrifice of Christ, the acts of the saints, the selflessness of the Virgin Mary, and the commitment of the martyrs, that one could draw upon for one’s own benefit in times of need. One could not simply “make a withdrawal” from the treasury, however; one had to promise to perform some penitential act which would repay this loan. That act was decided by one’s priest but, in cases where the person’s health or responsibilities made restitution difficult, a fine might be imposed which then went to building public institutions such as orphanages or sick-houses.

Pope Urban II, in 1095, issued a decree declaring absolution of sin for anyone taking part in the First Crusade (1095-1102) but those who could not participate could purchase an indulgence instead and the money would go toward funding the crusade. After this, the sale of indulgences was recognized as a significant source of revenue and, by 1400, indulgence sales were booming. Scholar John Bossy writes:

Indulgences had become attached to a variety of works, of which the most important was the crusade, but including public improvements like bridge or church-building; it had become established that these works could be performed by proxy, or commuted for money…Satisfactory penance due from one person could be made by another, provided the relation between the two parties was sufficiently intimate that what was done by one of them could be taken, by God and the Church, as being done by the other. (54)

Once indulgences were understood in this way, a person could purchase one for their deceased loved ones and the indulgence became a kind of spiritual promissory note that one would perform certain acts which would free the deceased from purgatory or, at least, lessen the time they were sentenced to suffer there for their sins. From this understanding, it was only a short step to the indulgence sales of c. 1500-1517 when purchasing an indulgence does seem to have been regarded as the “get out of sin free” card and the indulgence commissary was greeted in every village and town visited as royalty.

Tetzel & Luther

Between 1503-1509, Tetzel made a name for himself as an indulgence salesman traveling town to town and city to city. In 1508, he arrived in the mining town of St. Annaberg. A witness to his preaching, one Frederick Mecum, gives the following account:

He gained by his preaching in Germany an immense sum of money, all of which he sent to Rome; and especially at the new mining works at St. Annaberg, where I, Frederick Mecum, heard him for two years, a large sum was collected. It is incredible what this ignorant and impudent friar gave out [in his sermons]. He said that if a Christian had slept with his mother and placed the sum of money in the Pope’s indulgence chest, the Pope had power in heaven and earth to forgive the sin, and, if he forgave it, God must do so also. Item: if they contributed readily and bought grace and indulgence, all the hills of St. Annaberg would become pure massive silver. Item: so soon as the coin rang in the chest, the soul for whom the money was paid would go straightaway to heaven. The indulgence was so highly prized, that when the commissary entered a city, the Papal Bull was borne on a satin or gold-embroidered cushion, and all the priests and monks, the town council, schoolmaster, scholars, men, women, maidens, and children, went out to meet him with banners and tapers, with songs and procession. Then all the bells were rung, all the organs played; he was conducted into the church, and the Pope’s banner displayed; in short, God himself could not have been welcomed and entertained with greater honor. (Lindberg, Source 2.8; p. 29)

Tetzel preached in the area around St. Annaberg until 1510 and then falls out of sight, only emerging in the record again in 1516 when Archbishop Brandenburg asked Pope Leo X for the dispensation to sell indulgences and the pope sent Tetzel to Mainz. Brandenburg was deeply in debt to the Fugger Family of bankers who had loaned him the money to purchase his position as archbishop while Pope Leo X needed money for the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica. The men agreed to split the money collected by Tetzel but there is no evidence that Tetzel himself was aware of this deal. He seems to have understood that all the money would be going to Rome for St. Peter’s.

Luther was under this same impression and so, when he wrote his 95 Theses denouncing the sale of indulgences in 1517, he sent the work to Brandenburg with the understanding that his archbishop would be just as interested as he was in debating the policy and practices of their sale. Brandenburg had no such interest, however and, after having the work checked for heresy, sent it on to Rome. According to the traditional account, Luther nailed the 95 Theses to the Wittenberg church door, though this has been challenged and Luther himself only mentions sending the work to Brandenburg, but however it was first delivered, thanks to Gutenberg’s press, it was printed and in wide circulation by 1518.

In the last 50 years, scholars have debated whether Tetzel was the immediate inspiration for Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, but it seems quite clear that he was as Luther directly references his couplet regarding the gold in the box and the rescued soul in the 27th thesis and alludes to it in the 28th. In his letter to Brandenburg that accompanied the 95 Theses, Luther makes clear that he had been thinking of taking indulgence sellers to task for some time. Tetzel’s proximity was the catalyst that made him move on that impulse.

Throughout the early months of 1518, Luther and Tetzel exchanged arguments in print with Luther’s Sermon on Indulgences and Grace met by Tetzel’s rebuttal. Tetzel was by no means Luther’s intellectual or literary equal and Luther’s works consistently won more adherents to his “new teachings”. As Luther’s stature grew, Tetzel’s reputation suffered until, well before the end of the year, Tetzel’s works and the indulgences he had sold were being burned in communal fires. This same year, Tetzel was awarded his doctorate in theology but there is no evidence that he had enrolled in any university, and it is probable this was an honorary degree given to elevate Tetzel to the same academic position as Dr. Martin Luther. If so, it did nothing to improve Tetzel’s odds.

Conclusion

Luther eventually won in the court of public opinion and Tetzel was condemned as a charlatan who had sold his indulgences for personal profit. There is no evidence, however, that Tetzel ever took any of the money collected for himself as the coffers (caskets) people deposited their coins into were secured by three locks held by three separate people. Tetzel was even condemned by the Church he had served (though later pardoned) for his methods as well as his theology. His health began to fail, and he retired to the Dominican monastery where he had begun his career years before.

When word reached Luther that Tetzel was dying, he sent his former adversary a letter consoling him, but he also circulated the following story which did nothing to improve Tetzel’s reputation:

In 1517, there lived an impoverished and indebted knight, Christoph Haake von Stulpe, whose estate was completely rundown. Negotiations in nearby Juterbog with his principal creditor, the Cistercian cloister, did not provide a solution. However, while he was in the city, he witnessed all the fuss over Tetzel’s selling of indulgences. The sight of so much money flowing into Tetzel’s oaken indulgence chest gave him an inspiration.

When Tetzel finally left Juterbog, and traveled toward the cloister of Zinna, he was overtaken and robbed in a swampy area by the knight and his men. Tetzel, enraged, shouted to the robbers, “You shall be cursed and damned for eternity!” The knight raised his visor and Tetzel saw the laughing face of Haake whom Tetzel had earlier sold an indulgence for fifty guilder that remitted the future sin of robbery. (Lindberg, Source 2.9; p. 29)

There is no evidence that Tetzel ever sold an indulgence that would cover a future sin but, by the time this story was told, it was irrelevant what Johann Tetzel really did or did not do. After failing to meet the challenge of Luther’s attack on the Church, he was vilified, to greater or lesser degrees, by both Catholics and Luther’s followers. Modern-day scholarship has reevaluated Tetzel’s life and work, but he continues to primarily be understood as an unscrupulous indulgence salesman who fleeced gullible believers of money they could ill afford to part with.

There is certainly evidence to support this image, such as the Mecum account and other criticisms of the time, but it must be kept in mind that these were advanced by Protestant writers - including Luther - and may not be as accurate a depiction as previously thought. Tetzel's talent as a salesman is undeniable, however, and it seems clear that, in following his true vocation, he unwittingly inspired the Protestant Reformation.