The majority of great Renaissance works of art were produced in large and busy workshops run by a successful master artist and his team of assistants and apprentices. Here, too, more mundane art was produced in larger quantities to meet the demand from clients with a more modest budget than possessed by rulers and popes. Workshops were also training grounds for young artists who learnt their craft over several years, beginning with copying sketches and perhaps ending with producing works in their own name. Although workshops often had a well-defined house 'style', they were also places where ideas were experimented with and where new trends could be studied, discussed, and employed in works of art that ranged from massive frescoes to votive figurines.

The Establishment of Workshops

The people who produce art and decorative objects, those we today call 'artists', were, during the Renaissance, called 'craftsmen' and so belonged to the same broad category as cobblers, bakers, carpenters, and blacksmiths. Like these artisans, artists had workshops with the specialised equipment, materials, and space they needed for their work. As the Renaissance progressed, it is true that artists began to be distinguished from other craftworkers as there was an obvious intellectual element to their work - they studied the past and considered such theories as mathematical perspective, for example. Hitherto, the title of 'artist' had only been given to someone who had studied the seven liberal arts (rhetoric, grammar, dialectic, geometry, arithmetic, music, and astronomy). This development and elevation of the artist from other craftworkers also indicated that art had become an essential and important element in how a city or state viewed itself.

During the Renaissance many civic projects, but also some private ones like fresco cycles, could take many years to complete. Some projects needed large quantities of material and a team of artists, usually working under the supervision of the chief artist or his foreman, to complete them in good time. Consequently, when master artists were commissioned for specific projects, they were often given a dedicated space to create a workshop if they did not have one already or if it was more convenient to work on site. Donatello (c. 1386-1466 CE), for example, was commissioned to create sculptures for the exterior of Florence's cathedral and he was given space for his workshop in one of the Duomo's chapels. Running a workshop required all kinds of skills besides artistic ones. A master had to be discerning with contracts, manage and train staff, assess the quality of raw materials, budget his finances, invest any profits and, of course, never stop producing great art.

Some very successful artists even had workshops running in two or more cities at the same time. Just like today, a career in the arts could be a precarious one and some artists reduced the financial burden and risks by sharing a workshop. Donatello and Michelozzo di Bartolomeo (1396-1472 CE), for example, shared workshops in Pisa and Florence, which allowed them to save funds by sharing two boats and a mule for the transportation of marble needed for their work.

The Customers

During the Renaissance, generally speaking, art was not produced first and then sold later as it often is today, rather, artists were commissioned to produce specific pieces. Works of art were expensive and so the customers of a workshop were typically rulers, aristocrats (men and women), bankers, successful merchants, notaries, higher members of the clergy, religious orders and civic authorities and organisations like guilds. More humble clients might commission works for very special occasions such as a marriage or moving into a new home. Another popular demand for artworks was ex-votos, that is objects like plaques and small reliefs which believers wanted to leave in their local church as a thanks for propitious events which had happened in their daily lives. These ex-votos were part of the minority of works that a workshop produced without first having identified a specific buyer and so they would have likely been available 'over the counter' for a client to choose from.

Whoever the client, though, they were generally picky, and the artist's job was to produce exactly what they wanted. This was not mere whim on the part of the patrons as in that period art was not simply meant to be aesthetically pleasing. Rather, works of art had specific functions such as inspiring devotion, telling a Biblical story, or representing the history and abilities of a certain city or ruling family. For this reason, the artist had to follow certain conventions so that viewers could easily recognise religious, mythological, and historical figures.

Patrons and customers were, then, often not shy to stipulate exactly what they wanted to see in the finished work. Artists who diverged from these stipulations risked not having their work accepted or replaced (in the case of a fresco, for example). Haggling over the design and artist's fees set many a project back, whether it be a tomb for a Pope or a statue of a military leader. Contracts often stipulated a precise completion date, and this could be another source of friction between patron and artist. The contract might include a clause on just how much precious material - anything from gold to expensive colours - was used in the commission. A finished work might have to pass an assessment by a body of independent artists in the case of public works to ensure high quality. However, some artists were famous enough to push for complete control of a given project, even if there was sometimes an outcry from traditionalists when the work was finally revealed to the public. Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel frescoes are a good example of this when some clergy objected to the amount of nudity in his work. The fact that the destruction of the frescoes was seriously contemplated indicates just how dangerous it was for an artist to vary from convention, even one as renowned as Michelangelo.

There was a great rivalry between such Italian cities as Florence, Venice, Mantua, and Siena and so it was not uncommon for rulers and civic authorities to try and poach an artist away from one city and establish a new workshop elsewhere. Such authorities hoped the new art produced would enhance the prestige of their city and themselves. In addition, some artists were in such demand that they accepted more commissions than they could handle and so works were left unfinished or had to be completed by an assistant. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE) was notorious for not finishing off projects, and art patrons even wrote to each other warning of this fault.

The Apprentices

Workshops were not just places where art was produced but were training schools for the next generation of artists. Apprentices typically, but not always, followed their fathers into the artistic profession, as was common in other crafts. Other boys who showed artistic talent were sent to the workshop of a famous artist. Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE), the famed sculptor who worked for decades on the doors of the Baptistery of Florence, had a large workshop in that city. Many artists studied under Ghiberti or worked as his assistant, notably the sculptor Donatello and the painter Paolo Uccello (1397-1475 CE). In another example, the Florentine artist Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435-1488 CE) trained Pietro Perugino (c. 1450-1523 CE), Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510 CE) and Leonardo da Vinci. Perugino would himself go on to train Raphael (1483-1520 CE) in his workshop in Perugia. The Renaissance art world was really quite a small one and famed artists were certainly aware of what their rivals were producing, either in the next room of the workshop or in another city.

Apprentices were almost all boys (occasionally an artist apprenticed his own daughter), and they might be taken on as young as aged eleven or in their early teens. The training typically lasted from three to five years but could be less or more, depending on the ability and progress of the apprentice. The trainee was given food, lodging, and clothing, and sometimes a small wage. They would begin by doing the simple labour tasks necessary for the daily running of the workshop, then progress to making brushes from boar's hair, preparing glues and grinding pigments in marble basins. Next came such chores as mixing gesso, creating plaster, and preparing canvases.

The actual art skills typically began with drawing (using charcoal or ink), which was given great emphasis in the Renaissance period. Trainees endlessly copied drawings done by others and then progressed to creating new ones from three-dimensional casts. The final stage was to draw from live models, often fellow apprentices dressed as shepherds and angels or in the nude or wearing clothing that permitted an artist to perfect their representation of folded drapery. Another source of reality was drawing dead bodies and dissected limbs, which were acquired from local doctors and considered a useful way for painters and sculptors to better understand human musculature so that they could then better represent it accurately in art. Trips out and about in the city were organised to draw buildings, trees, and birds. As Leonardo da Vinci once recommended, any self-respecting artist should always carry a sketchbook with him to be ready to capture a new and interesting subject.

During the Renaissance, it was common for trainees to learn skills across different media such as fresco, panel painting using tempera or oil paints, large-scale sculpture in stone and metal, engraving, mosaic work, and the secrets of the goldsmith. Young artists learnt such practical skills as how to cast sculpture in metals like bronze and how to put these pieces together. They learnt the techniques of 'chasing' (finishing and polishing) and gilding the finished works. They learnt to mix colours and studied such techniques as chiaroscuro (the contrasting use of light and shade), sfumato (the transition of lighter into darker colours) and how to achieve a sense of perspective in a scene. Finally, and above all, an apprentice would learn how to reproduce the distinctive artistic methods of the workshop's master, the house 'style'.

The Assistants

An apprentice, having learned all of the above skills, would then graduate to becoming an assistant. Now he received a full salary and could work on behalf of the workshop's chief artist who then might sign his own name to the finished work of art (although some contracts stipulated important elements of a piece had to be created by the master himself). A gifted assistant would be trusted to fill in less important parts of a work the master was creating, for example, the hands of a figure, a background scene or applying areas of gold leaf. One can imagine that less-gifted assistants were entrusted with even more minor tasks like adding inscriptions and labels to works of art, a practice quite common in the Renaissance period.

An assistant might also join a guild of their city and so they could then produce works in their own right, even if they might still remain in the workshop rather than set up shop themselves, as was the case with Leonardo da Vinci early in his career. If they did want to establish their own workshop, then they first had to submit a 'masterpiece' for the approval of their local guild, which would then issue them with the right to do so (on payment of a fee). Another group within the workshop team, one rarely mentioned but nevertheless occasionally documented as existing, were slaves. Unlike an apprentice or assistant, they received no wage but a slave could, besides doing such obvious tasks as fetching, carrying, and cleaning, be trained in specific arts and produce works of their own.

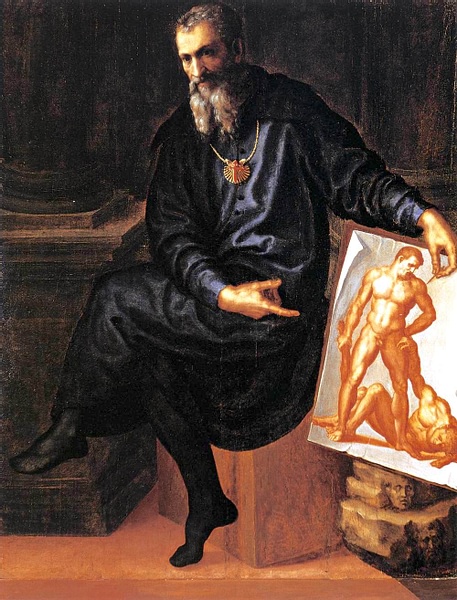

Besides the production of physical objects, ideas were studied and discussed in the workshop between the master and his assistants. Many noted artists built up their own collections of antiquities or portfolios of drawings of ancient art so that the study of these might help the workshop reproduce correctly anatomical details, proportion or classical motifs. There were, too, written texts discussing art and techniques. Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472 CE) wrote one such influential treatise, On Painting in 1435 CE. The master might also have contacts with other artists in other cities or abroad, another route for ideas and trends to filter down to the artists of tomorrow. As mentioned, these theoretical studies were an essential element in the progression of artists towards a more intellectual and elevated status in Renaissance society.

Mass Production & Forgeries

Despite all this attention to artistic learning and theory, many workshops became factories of art and most of their output was not the masterpieces we see today in museums worldwide but more mundane pieces meant as decoration in minor churches and less palatial homes. Perugino's workshop, for example, was noted for churning out endless altarpieces whose figures combined poses, heads, and limbs taken from a standard catalogue of drawings. These works were handmade and individualised by uniquely combining otherwise standard elements but they were the mass-produced art of the day and criticised as such by lovers of finer art. It was on these more humble works that most apprentices would have learnt their trade.

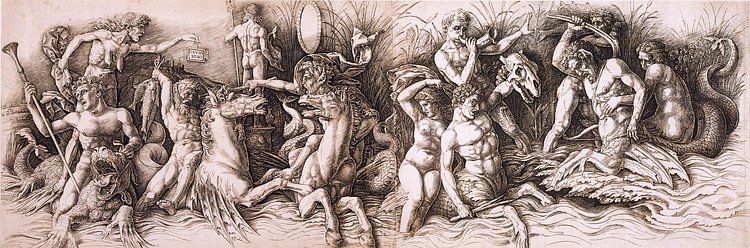

Another method to increase revenue and spread the reputation of a workshop was to produce copper-plate prints. These became increasingly popular from the 1470s CE onwards and not only allowed those of more modest means to own a piece of art but they also helped spread artistic ideas across Europe. Artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528 CE), amongst many others, compiled portfolios of prints and sketches of interesting works of art by other artists. The level of craftsmanship employed to produce engravings could be very high, and fine prints even began to be collected by connoisseurs.

Finally, a lucrative sideline - or for some more dubious workshops much more than that - was the production of fake antiquities. Such was the demand for Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek, and Roman pieces, some workshops produced modern versions and passed them off as ancient works, even sometimes staging an archaeological 'discovery' at a likely-looking site. Alternatively, new inscriptions were added to genuine antique pieces to make them more saleable. For the same reason, workshops often added missing limbs and noses to ancient statues or restyled older pieces, further blurring the lines between what was old and what was new art, a practice which has challenged art historians ever since.