An inscription on an Egyptian papyrus dating from the 2nd century CE relates that the goddess Isis, bestowing gifts on humanity at the beginning of time, gave as much power and honor to women as she did to men. This brief passage reflects not only the ancient Egyptian value of balance, but the high-status women enjoyed in ancient Egypt.

Although they never had the same rights as males, an Egyptian woman could own property in her own name and hold professions that gave her economic freedom from male relatives. Girls whose families could afford the tuition were educated along with boys beginning around the age of 7 and many went on to professional careers. Women could serve as clergy, practice medicine, handle money, travel alone for business purposes, and make real estate transactions. Most women, however, were groomed for marriage, became homemakers, and were taught by their mothers to cook, clean, sew, and weave.

A wife was entitled to one third of any property that she owned jointly with her husband and, on her death, could will her property to anyone she wished, male or female. Egyptian women were equal in the court system and could act as witnesses, plaintiffs, or defendants (as one would understand those terms today). Women were accountable for crimes they committed and would have to stand trial the same as any man.

The equality of the “gifts of Isis” did not mean, however, that women had completely equal rights with men; only that they were regarded as equals under the law. Egyptian society was patriarchal and hierarchical but, even so, offered women more rights than almost every other ancient civilization. This paradigm was observed from at least the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) until the fourth century and the rise of Christianity.

Education

Until the age of around 4, boys and girls were kept under the care of their mothers, usually residing in the women’s quarters of a home. After that age, boys began to learn their father’s trade or were sent to school, depending on the social class of the family. Girls remained with their mothers unless the father chose (and could afford) to send her to school. The Egyptian curriculum included astronomy, geography, mathematics, music, medical applications, reading, religion, writing, and physical education, among other subjects. Scholar Rosalie David comments:

Royal tutors taught some of the nobles’ children together with the king’s offspring, and future officials for the home and foreign services attended special training schools. Despite this hereditary pattern in the professions, some children of humble origin were able to receive education alongside the sons of the wealthy and powerful and to pursue important careers. However, education was not free, and each family was expected to pay in kind; in country areas, they would have offered the produce of the land. (205)

The” children of humble origin” could include girls if their parents could afford the cost and recognized either a certain aptitude or family need. An example might be a business the father wished to keep in the family and so wanted his daughters educated as accountants or supervisors, knowing he could trust them, but there is documentation of highly educated women who became career professionals such as Merit-Ptah, the royal court’s chief physician c. 2700 BCE and the first female doctor in world history known by name.

Women’s opportunities in ancient Egypt were determined by their social class, just as men’s were, having nothing to do with gender. Scholar Barbara Watterson notes:

The fact that, unlike women of most ancient civilizations and also of some modern countries, ancient Egyptian women enjoyed the same rights under the law as ancient Egyptian men, goes a long way towards explaining their relatively high social position. “You have made a power for the women equal to that of the men,” words written in praise of Isis, and quoted in a papyrus of the second century AD, might have been written with this in mind; and the point is one that many scholars have commented upon. The de jure rights of an ancient Egyptian woman depended on her class in society and not upon her sex. The king of Egypt was chief lawgiver and upholder of the law; and in theory everyone in Egypt, both male and female, noble and peasant, was equal under the law and had the right of access to the king in order to obtain justice. In practice, as might be expected, some, notably the rich and powerful, were more equal than others. (34)

Although the opportunity under the law was there for women to receive an education, however, did not mean that every woman could afford to seize it and many, if not most, may not even have been aware of their rights. Egypt was, generally speaking, an insular society and, especially in rural areas, a young girl may not have known that education was even a possibility. There is ample evidence, however, through correspondence, that many women could read and write even among the majority who married and raised a family.

Marriage & Family

Married women of means and land were known by the title Mistress of the House (today’s estate manager) and she would have supervised the workforce and overseen the servants who cared for her children. Women of the lower classes caried for the home, children, and her husband (and often the extended family) directly. Her responsibilities would include child rearing (unless she was wealthy enough to be able to afford a slave for the purpose) house cleaning, sewing, mending and making clothes, providing meals for the household, and managing the accounts.

There is also evidence of women tending to chores outside of the home such as the care of livestock, the supervision of workers in the fields (even doing field work herself) the maintenance of tools, buying and selling slaves and real estate, and taking part in the commerce of the marketplace; all of these rights and responsibilities, to this extent, the majority of the women of Greece and Rome never knew.

The Egyptian Wisdom Texts admonish husbands to treat their wives well since the balance between the male and the female resulted in harmony (known as ma'at) which was valued by the gods and, especially, the great goddess Ma'at. Marriage was considered a pact between a husband and wife for a lifelong commitment of equal partnership and companionship which could only be broken by death (which was the will of the gods, not of the individual marriage partners) although divorce was common in practice.

Women were legally protected against abuse from their husbands and, in the documents from a 12th Dynasty lawsuit, a man had to “swear that he would henceforth refrain from beating his wife, on pain of one hundred blows with a cane and the loss of everything he had acquired together with her” (Nardo, 35).

Women were also responsible for the happiness of the home, both in life and after death. Women's prestige was high enough that misfortune falling upon a widower was first attributed to some sin he had hidden from his wife which she, now all-knowing in the paradise of the Field of Reeds, was punishing him for. In a letter from a widower to his departed wife, found in a tomb from the New Kingdom, the man pleads with her spirit to leave him alone as he is innocent of any wrong-doing:

What wicked thing have I done to thee that I should have come to this evil pass? What have I done to thee? But what thou hast done to me is to have laid hands on me although I had nothing wicked to thee. From the time I lived with thee as thy husband down to today, what have I done to thee that I need hide? When thou didst sicken of the illness which thou hadst, I caused a master-physician to be fetched…I spent eight months without eating and drinking like a man. I wept exceedingly together with my household in front of my street-quarter. I gave linen clothes to wrap thee and left no benefit undone that had to be performed for thee. And now, behold, I have spent three years alone without entering into a house, though it is not right that one like me should have to do it. This have I done for thy sake. But behold, thou dost not know good from bad. (Nardo, 32)

Judgement, in these cases, would be made by a priest who would try to discern whether the spirit of the deceased wife was the cause of the man's misfortune or if there was some other cause. Interestingly, the ill-fortune a woman might suffer after the death of her husband was first attributed to the possibility she had neglected some important aspect of the funerary rites, then to a possible wrong she had committed against a god but, rarely, to any sin against her husband. When her husband died, a woman could inherit his business and run it as she pleased.

Occupations & Travel

Tombs and papyri depict women at various occupations such as singers, musicians, dancers, concubines, servants, beer brewers, bakers, weavers, cooks, professional mourners, and as dutiful wives, mothers, and daughters. Women were also scribes, physicians, priestesses, estate owners, and merchants. Women frequently traveled alone on business, as noted by scholars Roger S. Bagnall and Raffaella Cribiore comment:

Several letters reveal that women were likely to travel in order to carry out property management…their travels between estates, or from estates for business trips to cities, testify to the women’s high economic level. These women generally are property owners themselves. In [one letter], Diogenis, a landowner, gives orders regarding her property to her estate manager until she arrives to handle the business…[another] female landowner, from whom we have two letters, declares…that she is coming to the estate and wants everything in order. (82)

These women were powerful figures in their communities, commanding enormous respect, as Watterson notes:

She was her own mistress and, whether she was married or not, could act on her own behalf without being obliged to have a guardian act for her…A woman could buy and sell: if a woman owned property, she could dispose of it, whether it consisted of land or possessions, as she wished. In one papyrus, a certain Sebtitis cedes to her daughter half an aroura (0.34 acres) of corn-land; in another, several women acting together record a sale of land. (34)

This is hardly surprising when one considers the number of female deities – Bastet, Hathor, Isis, Neith, Seshat, Serket (Selket), among many others - in the Egyptian pantheon and how highly they were regarded by all the people of Egypt. The Divine Feminine was fully recognized and respected in ancient Egypt as evidenced not only by the goddesses but the women in positions of power.

God’s Wife of Amun

Beginning in the period of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), the position of God’s Wife of Amun was one of the most politically powerful in Egypt’s history. There were similar positions relating to other deities (wives of Ra and Ptah, for example) but, since Amun was the most powerful religious cult, a woman in this position exercised authority almost equal to the pharaoh by the time of the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE). These women were always the mother, wife, or eldest daughter of the king and officiated at festivals and religious ceremonies.

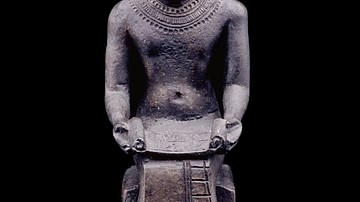

Among the most powerful included the queen Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE), queen Tiye (l. 1398-1338 BCE), wife of Amenhotep III, and Nefertari (l.c. 1255 BCE), wife of Ramesses II. These women are all depicted in powerful poses while those of lesser status appear in humbler images.

Women, no matter their class, were almost always shown as youthful with an emphasis on the female form. In tomb paintings, a man's wife, sisters and mother appear to be the same age because depictions of old age in a woman (past child-bearing years) was considered disrespectful to the individual who, after all, would be young and beautiful again after shedding the body and entering the afterlife of the Field of Reeds. While they lived, women cared for their appearance, as did men, making use of cosmetics, dyes, and wigs to accessorize their clothing.

Fashion & Accessories

Women in ancient Egypt placed great value on personal appearance, hygiene, and grooming. Egyptian women (and men) bathed several times a day in a soda-mix with water (the Egyptians had no knowledge of soap). Henna was used to dye the hair, nails, and even the body. Unlike other cultures of the time (Greece, for example) women could cut their hair short if they liked and many women shaved their heads and wore wigs. Rosalie David comments on the fashion:

Women of the nobility and upper classes are shown in narrow dresses held under the bosom by two wide straps suspended from the shoulders. From the New Kingdom, they also often added a cloak. Generally, for the wealthy, the clothes of both sexes became more voluminous in the later New Kingdom when transparently fine garments were worn over the basic undergarments. (290)

Tomb paintings depict the deceased in the latest fashions in wigs, clothing, and makeup. Cosmetics were not considered a luxury but a necessity for daily life and many examples of makeup, perfume, and toiletry items have been found in tombs.

Conclusion

Although women in all levels of Egyptian society continued to depend on the males of the family for sustenance and status, they still enjoyed greater freedoms and responsibilities than women almost anywhere else in the known world at that time. The cosmopolitan and cultured manner of Egyptian women is often emphasized in tomb paintings and reliefs and it is worth noting that the famous pharaoh Cleopatra, though Greek, adopted Egyptian ways and was noted for her refinement and charm.

Women continued to be highly respected in Egypt and share equal rights with men until the coming of Christianity. This religious and cultural event also brought a marked decline in personal hygiene since, from the 1st century on into the 4th and later, it was thought that Jesus Christ would return at any moment and so personal appearance was irrelevant and, further, attention to the body was not only considered vanity but a throwback to pagan practices.

The Christian scriptures preached the inferiority of females to males through passages including “the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man” (I Corinthians 11:3) and “I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence” (I Timothy 2:12). Women’s rights in Egypt declined further after the arrival of Islam and the gifts of Isis, bestowed equally on men and women, were forgotten.