Trade and commerce in the medieval world developed to such an extent that even relatively small communities had access to weekly markets and, perhaps a day's travel away, larger but less frequent fairs, where the full range of consumer goods of the period was set out to tempt the shopper and small retailer. Markets and fairs were organised by large estate owners, town councils, and some churches and monasteries, who, granted a license to do so by their sovereign, hoped to gain revenue from stall holder fees and boost the local economy as shoppers used peripheral services. International trade had been present since Roman times but improvements in transportation and banking, as well as the economic development of northern Europe, caused a boom from the 9th century CE. English wool, for example, was sent in huge quantities to manufacturers in Flanders; the Venetians, thanks to the Crusades, expanded their trade interests to the Byzantine Empire and the Levant, and new financial instruments evolved which allowed even small investors to fund the trade expeditions which criss-crossed Europe by sea and land.

Markets & Shops

In villages, towns, and large cities which had been granted the privilege of a license to do so by their monarch, markets were regularly held in public squares (or sometimes triangles), in wide streets or even in purpose-built halls. Markets were also organised just outside many castles and monasteries. Typically held once or twice a week, larger towns might have a daily market which moved around different parts of the city depending on the day or have markets for specific goods like meat, fish, or bread. Sellers of particular goods, who paid an estate owner, the town, or borough council a fee for the privilege to have a stall, were typically set next to each other in areas so that competition was kept high. Sellers of meat and bread tended to be men, but women stallholders were often the majority, and they sold such staples as eggs, dairy products, poultry, and ale. There were middlemen and women known as regrators who bought goods from producers and sold them on to the market stallholders or producers might pay a vendor to sell their goods for them. Besides markets, sellers of wares also went knocking on the doors of private homes, and these were known as hucksters.

Trade of common, low-value goods remained a largely local affair because of the costs of transportation. Merchants had to pay tolls at certain points along the road and at key points like bridges or mountain passes so that only luxury goods were worth transportation over long distances. Moving goods by boat or ship was cheaper and safer than by land but then there were potential losses to bad weather and pirates to consider. Consequently, local markets were supplied by the farmed estates that surrounded them and those who wanted non-everyday items like clothing, cloth, or wine had to be prepared to walk half a day or more to the nearest town.

In towns, the consumer had, besides markets, the additional option of shops. Tradespeople usually lived above their shop which presented a large window onto the street with a stall projecting out from under a wooden canopy. In cities, shops selling the same type of goods were often clustered together in the same neighbourhoods, again to increase competition and make the life of city and guild inspectors easier. Sometimes location was directly related to the goods on sale such as horse sellers typically being near the city gates so as to tempt the passing traveller or booksellers near a cathedral and its associated schools of learning. Those trades which involved goods whose quality was absolutely vital such as goldsmiths and armourers were usually located near a town council's administration buildings where they could be kept a close eye on by regulators. Towns also had banks and money-lenders, many of which were Jews as usury was forbidden to Christians by the Church. As a consequence of this clustering of trades, many streets acquired a name which described the trade most represented in them, names which in many cases still survive today.

Trade Fairs

Trade fairs were large-scale sales events typically held annually in large towns where people could find a greater range of goods than they might find in their more local market and traders could buy goods wholesale. Prices also tended to be cheaper because there was more competition between sellers of specific items. Fairs boomed in France, England, Flanders, and Germany in the 12th and 13th centuries CE, with one of the most famous areas for them being the Champagne region of France.

The fairs which were held in June and October in Troyes, May and September in Saint Ayoul, at Lent in Bar-sur-Aube, and in January at Lagny were encouraged by the Counts of Champagne who also provided policing services and paid the salaries of the army of officials who supervised the fairs. Traders of wool, cloth, spices, wine, and all manner of other goods gathered from across France and even came from abroad, notably from Flanders, Spain, England, and Italy. Some of these fairs lasted up to 49 days and brought in a healthy revenue to the Counts; such was their importance, French kings even guaranteed to protect merchants travelling to and from the fairs. Not only did the fairs of Champagne become famed across Europe but they were a great boost to the international reputation of Champagne wine (at that time still not the sparkling drink that Dom Pérignon would pioneer in the 17th century CE).

For many ordinary people, fairs anywhere were a great highlight of the year. People usually had to travel more than a day to reach their nearest fair and so they would stay one or two days in the many taverns and inns which developed around them. There were public entertainments such as the dancing girls of Champagne and all kinds of performing street artists as well as a few more unsavoury aspects such as gambling and prostitution that gave the fairs a poor reputation with the Church. By the 15th century CE trade fairs had gone into decline as the possibilities for people to buy goods everywhere and at any time had greatly increased.

The Expansion of International Trade

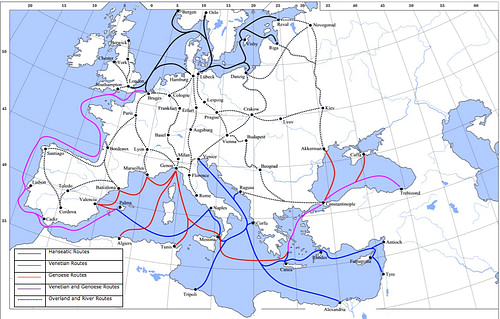

Trade in Europe in the early Middle Ages continued to some degree as it had under the Romans, with shipping being fundamental to the movement of goods from one end of the Mediterranean to the other and via rivers and waterways from south to north and vice versa. However, the extent of international trade in this early period is disputed among historians. There was a movement of goods, especially luxury goods (precious metals, horses, and slaves to name a few), but in what quantities and whether transactions involved money, barter, or gift-exchange is unclear. Jewish and Syrian merchants may have filled the gap left by the demise of the Romans up to the 7th century CE while the Levant also traded with North Africa and the Moors in Spain. It is probable that international trade still remained the affair of only the elite aristocracy and it supported economies rather than drove them.

Into the 9th century CE, a clearer picture of international trade begins to emerge. The Italian city-states, under the nominal rulership of the Byzantine Empire, began to take over the trade networks of the Mediterranean, particularly Venice and Amalfi who would later be joined by Pisa and Genoa and suitable ports in southern Italy. Goods traded between the Arab world and Europe included slaves, spices, perfumes, gold, jewels, leather goods, animal skins, and luxury textiles, especially silk. Italian cities specialised in the exports of cloths like linen, unspun cotton, and salt (goods which originally came from Spain, Germany, northern Italy, and the Adriatic). There developed important inland trading centres like Milan which then passed on goods to the coastal cities for further export or more northern cities. The trade connections across the Mediterranean are evidenced in descriptions of European ports in the works of Arab geographers and the high numbers of Arab gold coinage found in, for example, parts of southern Italy.

In the 10th and 11th centuries CE, Northern Europe also exported internationally, the Vikings amassing large numbers of slaves from their raids and then selling them on. Silver was exported from the mines in Saxony, grain from England was exported to Norway, and Scandinavian timber and fish were imported in the other direction. After the Norman Conquest of Britain in 1066 CE, England switched trade to France and the Low countries, importing cloth and wine and exporting cereals and wool from which Flemish weavers produced textiles.

As the Italian trio of Venice, Pisa, and Genoa gained more and more wealth, so they spread their trading tentacles further, establishing trading posts in North Africa, also gaining trade monopolies in parts of the Byzantine Empire and, in return for providing transport, men and fighting ships for the Crusaders, a permanent presence in cities conquered by Christian armies in the Levant from the 12th century CE. In the same century, the Northern Crusades provided southern Europe with yet more slaves. Also travelling south were such precious metals as iron, copper, and tin. The 13th century CE witnessed more long-distance trade in less valuable, everyday goods as traders benefitted from better roads, canals, and especially more technologically advanced ships; factors which combined to cut down transportation time, increase capacity, reduce losses and make costs more attractive. In addition, when the goods arrived at their point of sale, more people now had surplus wealth thanks to a growing urban population who worked in manufacturing or were traders themselves.

Trading Ports & Regulation

International business was now booming as many city-ports established international trading posts where foreign merchants were allowed to live temporarily and trade their goods. In the early 13th century CE Genoa, for example, had 198 resident merchants of which 95 were Flemish and 51 French. There were German traders on the famous (and still standing) Rialto bridge of Venice, in the Steelyard area of London, and the Tyske brygge quarter of Bergen in Norway. Traders from Marseille and Barcelona permanently camped in the ports of North Africa. Economic migration reached such numbers that these ports developed their own consulates to protect the rights of their nationals and shops and services sprang up to meet their particular tastes in food, clothing, and religion.

With this growth, trade relations became more complex between states and rulers, with middlemen and agents added to the mix. Trading expeditions were financed by rich investors who, if they put up all the initial capital, often got 75% of the profits, the rest going to the merchants who amassed the goods and then shipped them to wherever they were in demand. This arrangement, used for example by the Genoese, was called a commenda. An alternative setup, the societas maris, was for the investor to provide two-thirds of the capital and the merchant the rest. The profits would then be split 50-50. Behind these major investors, there developed consortiums of smaller investors who put up their money for a future return but who could not afford to pay for a whole expedition. Thus, there developed sophisticated mechanisms of borrowing and lending, which involved a very large number of families in the Italian cities, in particular. There were more and more financial instruments to tempt investors and extend credit such as credit notes, bills of exchange, maritime insurance, and shares in companies.

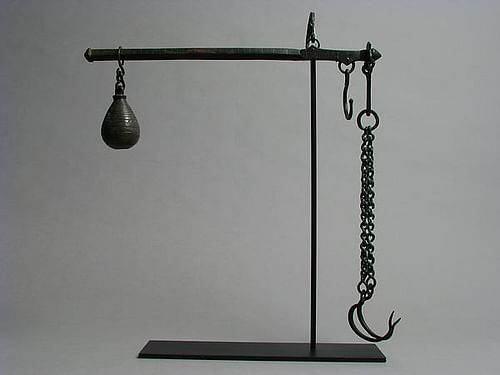

Trade was now assuming the guise we would recognise today with well-established businesses run by generations of merchants from the same family (for example, the Medici of Florence). There were increased efforts at standardisation in product quality and helpful treatises on how to compare weights, measurements, and coins across different cultures. State control increased with a codification of customary trade laws and regulations and, so too, the now all-too-familiar imposition of taxes, duties, and protectionist quotas. Finally, there was, as well, advice on how to best get around these regulations, as mentioned in this extract on Constantinople's trade officials, taken from the 14th-century CE Florentine trader Francesco Balducci Pegolotti's guide to world trade, La Practica della Mercatura:

Remember well that if you show respect to customs officials, their clerks and 'turkmen' [sergeants], and slip them a little something or some money, they will also behave very courteously and will tax the goods that you later bring by them lower than their real value. (Blockmans, 244)

By the mid-14th century CE, the Italian city-states were even trading with as distant partners as the Mongols, although this increase in global contact brought unwanted side effects such as the Black Death (peaked 1347-52 CE) that entered Europe via the rats which infested Italian trading ships. Undeterred, European pioneers - both religious and commercial - would head off into the other direction, and so the Cape Verde Islands were discovered by the Portuguese in 1462 CE and three decades later Christopher Columbus would open up the way to the New World. Next, in 1497 CE, Vasco da Gama boldly sailed around the Cape of Good Hope to reach India so that by the end of the Middle Ages, the world was suddenly a much more connected place, one which would bring riches for a few and despair for many.