The society in the Byzantine Empire (4th-15th century CE) was dominated by the imperial family and the male aristocracy but there were opportunities for social advancement thanks to wars, population movements, imperial gifts of lands and titles, and intermarriage. The majority of the lower classes would have followed the profession of their parents, but inheritance, the accumulation of wealth, and a lack of any formal prohibition for one class to move to another did at least offer a small possibility for a person to better their social position. In Constantinople and other cities, foreign merchants, mercenaries, refugees, travellers, and pilgrims were constantly passing through or establishing themselves permanently within the empire so that Byzantium became famously cosmopolitan; a fact noted by contemporary visitors who recorded their astonishment at the diversity of the society they visited.

Aristocracy

Byzantine society, as in that of later Roman society in the west, has been traditionally divided into two broad groups of citizens: the honestiores (the “privileged”) and the humiliores (the “humble”), that is, the rich, privileged, and titled as opposed to everyone else (except slaves who were an even lower category). These two terms were applied in Roman law throughout antiquity. The honestiores traditionally included senators, equestrians, decurions, and veterans, and their treatment in terms of legal punishments was more lenient than that of the humiliores, in most cases being composed of fines rather than corporal punishment. For serious crimes such as murder and treason, no social distinction was made. Just how distinct these two groups were in everyday life is less clear, but there was a general prejudice against those of a lower social position and a greater respect and trust for those with titles, wealth, and positions of power.

There was a huge divide in terms of living standards between the haves and have-nots, a situation commented on and criticised by many Byzantine Christian writers. This division was perpetuated by the importance given to the family name, inherited wealth, and the respectable birth of an individual so that it was very difficult, but certainly not impossible, for a person to rise the social ladder. There was no aristocracy of blood as such in Byzantine society, and the ever-changing dynasties of emperors over the centuries and their often random dispensing of favours, lands and titles, as well as indiscriminate demotions and the hazards of foreign invasions and wars, all meant that the individual components of the nobility were not static and families rose and fell over the centuries.

The aristocracy derived their wealth and status from land ownership. Initially, this was based on the old Roman system of large estates worked on by peasants who were bound to the land (coloni), but there developed a new military aristocracy (dynatoi) from the 10th century CE. This latter group derived their authority and ownership from the administrative division of the empire's territory into regions (themes), which was in response to the increasing number of attacks and invasions from such enemies as the Bulgars and Arab caliphates.

Land ownership was inherited but it could also be granted by the emperor or removed, especially when an emperor thought certain families were becoming too much of a threat to his own position. The emperors were constantly fighting the tax evasion of the landed aristocracy, too, and attempts were made (largely unsuccessful ones) to prevent greedy aristocrats from buying up land and reducing the peasantry to no more than tenant farmers (paroikoi). The all-encompassing power of the emperor over not only the aristocracy but everyone else is here summarised by the historian J. Herrin:

The court exercised a hegemonic power which integrated all sectors of society and reinforced imperial authority; it was recognized as the centre of superior culture and unrivalled brilliance. Ambitious provincial inhabitants usually identified with it and aspired to a place in it. (172)

Within the upper classes, there were further layers of status based on one's family name and who one knew. Patronage was an important factor in easing one's progress through life, and just as today, who one went to school with, who were one's friends, family, and who one shared political and religious views with helped determine one's career and the opportunities available for social advancement.

One method of gaining access to the higher levels of society, even if one was handicapped by not possessing a noteworthy family name or patron, was education, as here explained by Herrin:

And because leading positions in all spheres were open to talent, education was seen as a means of social mobility, a key to the rewards of high office and social prominence. In a circular process, the education of younger members might bring an increase in family fortunes, which benefitted all relations, who in turn invested in the educational facilities and intellectual activities which consolidated and enhanced the status of scholars in Byzantium. (119)

Besides titles and forms of address, the aristocracy were easily identified by their status symbols such as fine jewellery and silk clothing. Certain high-ranking officials even had their own distinct clothes of office. The colour of a cloak, tunic, belt, and shoes, or the particular design and material of a fibula could indicate visually the wearer's office. Indeed, some of the buckles worn were so precious and the risk of theft so high that many officials wore imitations made from gilded bronze. Additional badges of rank included small ivory plaques, metal stamped disks, a gold collar or gilded whip. Even the correspondence of people of rank contained clear indicators of their status such as titles and stamped lead seals.

Lower Classes

The lower classes of Byzantine society worked for a living in all the industries of the day with the more successful ones owning their own small businesses. Thus, this section of society would include the middle class if we were to apply modern terms. There were, at the top, what we would today call 'white-collar' workers who had acquired specific knowledge through education such as lawyers, accountants, scribes, minor officials and diplomats, all of whom were essential to the efficient running of the state.

Even at the top end of this broad social group, there was not much respectability to be had in the eyes of the upper classes. Traders, merchants, and even bankers might have been extremely rich, but they were held in low esteem by the aristocracy and Byzantine religious art frequently portrays these professions being tormented in hell for their dishonesty and sharp practices. It is also no coincidence that the state imposed all kinds of checks and controls on markets, the prices of goods, and the weights used by merchants. Those who made money from others had to be watched carefully. Nevertheless, the steady march of commerce meant that by the 12th century CE merchants were beginning to join the ruling, land-owner class.

The next level down was the craftsmen and food producers who were rather less socially mobile as members of the major guilds (collegia) were expected to remain in their professions and pass on their skills to their children. Whether the expectation was met in practice is a moot point, but there must certainly have been a feeling of constraint which perpetuated the convention that everyone had their place in society and it was a fixed one.

Finally, and by far the largest population group, there were the small-scale farmers who owned their own land and the most humble citizens of all who worked as agricultural labourers (coloni) for others. This latter group were not very much higher or treated better than slaves who were the lowest of the low.

Slaves

Slaves were ever-present in Byzantine society, and they came from conquered peoples, prisoners of war, and from slave markets. They were brought into the empire in great numbers, especially from the Balkan peninsula and around the Black Sea, but they never outnumbered free-peasant labour in rural areas. This is probably because a slave was always a pricey commodity costing around 30 gold coins in the 5th century CE (a pig would set you back one and a donkey three). It is one of the oddities of Byzantium that slavery continued despite the acknowledgement from the Church that all humans were equal before God whatever their social status. Such was the importance of slavery to the functioning of the state, and especially the imperial workshops that the Church adopted a conciliatory policy of toleration rather than seek its cessation.

Women & Children

Aristocratic women were largely expected to run the family home, look after the children, and supervise the servants and property. They did not live a secluded life but neither could they hold any public office of note. They learnt to spin, weave, and to read and write but had no formal education. Expected to marry, women could own their own property and their dowry. They could also assume the role as head of the family if they were left a widow. Divorce procedures were in favour of the male and not easy to achieve, in any case, for either party.

Working women earned their living doing pretty much what many working men did - they could own their own businesses or work for others such as in the agricultural, manufacturing, medical, and retail sectors. The lowest class of women were actresses and prostitutes. Social advancement could be achieved through marriage but, as with men, most women would have learnt the profession of their mothers. Some women did make spectacular progress up the social ladder by marrying into higher-class families, even sometimes into the imperial family itself and to become empresses by winning bride shows organised for that purpose.

As mentioned above, education (for males) was an important opportunity for social advancement, and most cities had a school ran by the local bishop. Young men whose parents could afford it were first taught to read and write in Greek and then schooled in the seven classical arts of antiquity: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, harmonics, and astronomy. Higher education consisted in the study of philosophy, especially the works of Plato and Aristotle, as well as Christian theology.

Eunuchs

Although not unique to Byzantium, an interesting feature of society and government was the use of eunuchs in the royal court at Constantinople and the wider state administration. Indeed, the great number of eunuchs in Constantinople in general often astonished foreign visitors. As they had no heirs and no sexual appetite (in theory anyway), the idea was that eunuchs could be trusted to serve the emperor and the state without lining their own pockets or philandering with the ladies of the imperial household. The personal attendants of the emperor - those who served his food and dressed him - were eunuchs too, as were many important figures in the Church, including bishops, and several successful generals in the army.

Many parents were very willing to send their children as eunuchs to the palace in the hope of gaining positions of favour there, just as girls were sent to try and gain positions as ladies-in-waiting. There was also a significant slave trade specialising in eunuchs, castration not being an uncommon treatment of prisoners of war. Consequently, many upper-class households had eunuch slaves to look after the women of the house and teach the children. The practice of self-harm was at odds with the Church, and self-castration was officially prohibited. Still, the churches of Constantinople were happy enough to employ choirs of castrati, a practice later copied in Rome and the Vatican. Finally, castration and other physical mutilations were a common punishment in Byzantine law, indicating the general social disdain in which eunuchs were held by just about everybody.

The Clergy

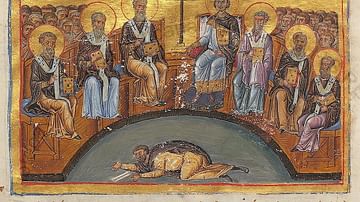

As Christianity was widely practised, the members of its clergy were many and important to their communities. The clergy and church were headed by the Patriarch (bishop) of Constantinople but emperors, too, sometimes concerned themselves with church policies and even doctrines. The appointment and removal of the Patriarch was also the prerogative of the emperor, a right used many times to install like-minded bishops or remove those who proved an obstacle to imperial plans such as re-marriages or the destruction of icons. Local bishops, who presided over larger towns and their surrounding territories and who represented both the church and emperor, had considerable wealth and powers.

There were some social restrictions on the clergy. Priests and deacons were permitted to have wives if they had married before being ordained while bishops were obliged to separate from their spouses. The bishop's wife's position was even worse as she had to then retire to a monastery. Naturally, many women could freely choose an ecclesiastical life in the many monasteries dedicated specifically to them where nuns devoted themselves to Christ and helped the poor and ill.

Foreigners

Amongst all the different social levels already mentioned there were foreigners and non-Christians who made Byzantium a very cosmopolitan society. The Byzantine Empire conquered many lands and these peoples were incorporated into the existing structure of society - many thousands of people were forcibly displaced, still more sought a better life than that in their birthplace, and the army itself gave employment to Scandinavians, Russians, Armenians, Anglo-Saxons, and Germans amongst others. Traders, merchants, and craftworkers migrated to where they could earn a living from their skills and goods. Jews were prevalent in the areas of money-lending and textiles, Muslim traders from Arabia peddled their wares in the local markets, and Italian merchants came from the great trading cities of Genova, Pisa, and Venice. There was not always harmony between these groups, however, as shown by the infamous riot of 1042 CE when the local traders of Constantinople attacked their foreign rivals. Finally, Christian pilgrims from all over Europe passed through to see the Empire's sacred sites and relics on their way to the Holy Lands.