Constantine VI, also known as Constantine "the Blinded”, was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 780 to 797 CE, although for most of his reign his mother, Irene the Athenian, ruled as regent. When Constantine did finally get a go at ruling in his own right, he was anything but successful. Deposed by his own mother, Constantine was infamously blinded by her in the royal palace and, as was the intention, he died from his injuries.

Succession & Irene's Regency

Constantine was the son of Leo IV (r. 775-780 CE) and when, in 780 CE, his father died of fever, aged just 30, Constantine became emperor Constantine VI. However, as the new emperor was still a minor at nine or ten years of age, his mother Empress Irene ruled as his regent, a role she performed until 790 CE. Irene had immediate problems and had to quash a rebellion led by the other sons of Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE) and half-brothers of Leo IV. Once that was dealt with, she ensured the loyalty of the palace entourage by dismissing any ministers and military commanders of questionable affiliation. To this end, she trusted two court eunuchs, in particular, Staurakios and Aetios.

Irene attempted to further entrench her position by arranging a marriage alliance with the Franks and promising Constantine to Rotrude, the daughter of the Franks' king Charlemagne. For unknown reasons, Irene changed her mind, though, and in 787 CE she found an alternative wife for her son, one Mary of Amnia, a pious but slightly boring girl selected via the traditional “bride show” which Byzantine rulers organised for their offspring. The Frankish-Byzantine alliance would have been an intriguing one and joined the two halves of the old Roman Empire but the opportunity would come around again, as we shall see.

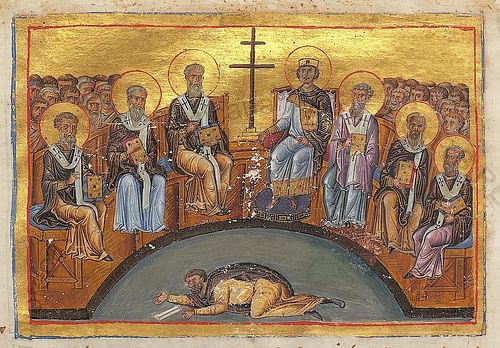

As ever, the borders of the Byzantine Empire needed constant vigilance and defence. Irene enjoyed certain successes against both the Slavs in Greece and Arabs in Asia Minor. Closer to home, Irene convened a Church council in Constantinople in 786 CE which, despite initial opposition from members of the army who thought defeats on the battlefield were God's punishment for the widespread veneration of icons, decreed an official end to iconoclasm, that is, the destruction of icons, a key feature of her predecessor's reigns. The regent then went one step further and invited 350 bishops to the Seventh Ecumenical Council in September 787 CE which ruled to restore the orthodoxy of the veneration of icons in the Christian Church.

Irene's Exile

Traditionally, a Byzantine monarch took their place on the throne when they reached 16 years of age and the regent gracefully stepped aside. Not so for Irene, the first ominous sign being the removal of Constantine's face from the imperial coinage. When Irene made it be known that she intended to rule above her son Constantine no matter how old he was, many of those who opposed the restoration of icons, saw the dangers to the empire's army strength Irene's purges had threatened, and who believed Constantine had the rightful claim to the throne alone, rallied around the young emperor. Irene responded by executing seven dissenting generals and throwing her son in prison, but by 790 CE both the army and an anti-Irene mob came to Constantine's support, stormed the prison, and released him. Fortunately for the young emperor, the army still contained many iconoclasts, and many had refused to swear loyalty to Irene alone on religious grounds.

Now 19 years of age and keen to remove his interfering mother once and for all from state affairs, Constantine banished her from court along with her closest advisors while he engaged as his own advisor Michael Lachanodrakon, the influential general and governor of the Thrakesion region of the empire. After a decade in the shadows, Constantine took his rightful place at the apex of Byzantine government.

Constantine As Emperor

Unfortunately, the young emperor was not actually up to the task of ruling. Serious and immediate defeats against the Bulgars and a shameful truce against the Arabs did nothing to aid his popularity. Even on the battlefield, where an emperor might gain some admirers for heading his own troops, Constantine's cowardice had been revealed as he panicked and fled before the enemy. Now, back at court, conspiracies were rife. One led by Constantine's uncle Nikephoros was quashed, and the emperor blinded the ringleader in an all too familiar act of imperial Byzantine brutality. Constantine then ordered the tongues of all four of his uncles to be torn out. The emperor then created another problem when he blinded Alexios Mousele the droungraios tes viglas or Commander of the Imperial Watch, an act which sparked off yet another rebellion, this time in the province of Armeniakon in northeastern Asia Minor.

Irene was not to be so easily ushered to the wings of power, either, and she returned to the court in 792 CE, invited by her son as a last-ditch attempt to restore some order to his reign. In effect, they ruled jointly for the next five years, but Irene soon began to plot against her son. Significantly, Constantine could no longer call on the support of Michael Lachanodrakon, the general having been killed that year while campaigning against the Bulgars. The army was all too unimpressed with the young emperor, and his popularity plummeted even further when he began to blame his soldiers for their defeats, taking the ill-advised action (cunningly suggested by Irene, of course) of tattooing the word “traitor” on the faces of 1,000 of them.

A final crushing blow to Constantine's ambitions was the protests following his divorce from Maria and subsequent marriage to his mistress Theodote, the so-called Moechian Controversy, in 795 CE. To make matters worse, the couple had a son 18 months later. Two monks were especially vociferous in their outrage at the emperor's behaviour as head of the Church, Plato of Sakkoudion and Theodore of Stoudios, who both claimed that his divorce was illegal and so in marrying again the emperor had committed adultery. The emperor had lost the support of the one group he could always depend on; the iconophiles. Constantine's unpopularity with his people and the Byzantine establishment meant that he had no friends left to block his removal from power by his own mother.

Death & Irene As Empress

In 797 CE, when Irene took back the throne for herself, she had her son detained while out riding and, on 15 August, had him blinded, doing so in the same purple chamber of the palace in which he had been born. The Porphyra room was a powerful symbol of an emperor's legitimacy and right to rule, and, therefore, the act was as bold a statement as possible of Irene's intent, not to mention her callousness. There was not going to be another rebellion against her rule. Constantine died shortly afterwards, almost certainly as a result of his injuries, which were intended to kill not maim. With his heir having already died earlier the same year, Irene had now dealt with all of her challengers. Thereafter, Irene is referred to in official state records as basileus, emperor, and not as empress, the first woman to so rule in her own right.

Irene, as unpopular as ever and now infamous for her actions towards her son, would not reign for long. Hefty tributes to the Arabs in order to stave off further incursions into Byzantine territory made a serious dent in the state treasury and the constant whiff of rebellion around the palace meant that Irene's position was precarious. Then, in 802 CE, there was the last straw. Irene attempted a marriage of alliance with Charlemagne, now the newly declared Emperor of the Romans in the west. It simply would not do, though, for a Byzantine emperor to marry an illiterate barbarian (as the Byzantines thought of him) and the nobles convened in the Hippodrome of Constantinople to declare that Irene must be removed from office. Exiled to a monastery on Lesbos, she was succeeded by Nikephoros I (r. 802-811 CE), one of the Empress' former finance ministers. Irene died within a year of losing the throne she had loved so much and clung onto for so long. Meanwhile, the empire stumbled on, still trying to regain its former glory but without very much success.

In a bizarre postscript, Constantine VI did, in a sense, later return from the dead in the guise of the usurper Thomas the Slav, who led a rebellion against emperor Michael II (r. 820-829 CE) between 821 and 823 CE. Thomas, to add legitimacy to his otherwise spurious claim to the Byzantine throne, spread about the story that Constantine VI had not, in fact, died when his mother Irene had blinded him but had managed to escape Constantinople and he was the very same person, dead set on getting back what was rightfully his. Thomas even had himself crowned emperor in Antioch, but it was all to no avail and his rebellion was quashed by Michael in 823 CE.