Theodora reigned as empress of the Byzantine Empire alongside her husband, Emperor Justinian I, from 527 CE until her death in 548 CE. Rising from a humble background and overcoming the prejudices of her somewhat disreputable early career as an actress, Theodora would marry Justinian (r. 527-565 CE) in 525 CE and they would rule together in a golden period of Byzantine history. Portrayed by contemporary writers as scheming, unprincipled, and immoral, the Empress, nevertheless, was also seen as a valuable support to the Emperor, and her direct involvement in state affairs made her one of the most powerful women ever seen in Byzantium.

Early Life

Theodora was born in c. 497 CE, the daughter of a bear-keeper called Akakios who worked for the Hippodrome of Constantinople. The 6th-century CE Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea states in his Secret History (Anekdota) that Theodora earned her living, like her mother before her, as an actress, which meant performing in the Hippodrome as an acrobat, dancer, and stripper. Theodora was said to have had one particularly lurid routine involving geese. By implication, considering the common association of the two professions at the time, she was also a courtesan. Procopius would have us believe an especially popular and lustful one, at that.

Procopius' Secret History, is, though, regarded by many as an outrageous gossip piece with a few facts thrown in for authenticity. The writer's attitude to both Justinian and Theodora is plainly that they were the worst thing ever to happen to the Byzantine Empire (in contrast to the official works he wrote under Justinian's patronage which are suitably laudatory of the emperor's achievements in war and architecture especially). Procopius also had it in for Antonina, the wife of Belisarius (Justinian's most talented general), and she is portrayed as constantly scheming with Theodora to create damaging palace intrigues. It is perhaps important to consider, too, that our knowledge of Theodora only comes from male authors and a woman performing any other role than the traditionally submissive one in Byzantine society was bound to be, at best, disapproved of and, at worst, outright demonised.

Before she married Justinian, the nephew of Emperor Justin (r. 518-527 CE), in 525 CE, Theodora left the sands of the Hippodrome to travel to North Africa as the mistress of a medium-level civil servant. After the relationship broke up, she made her way back home via Alexandria where she may have converted to Christianity.

The marriage between such a lowly figure as Theodora and a future emperor was an odd rags-to-riches one, but there was a tradition in the Byzantine court for emperors to marry the winners of beauty contests organised for that purpose. The entrants to such contests could come from lower classes and from far away provinces so such mismatches were not unheard of. The lowly status of Theodora was not ignored by everyone, and one particularly passionate opponent was Empress Lupicina Euphemia, indeed, her death seems to have removed the foremost obstacle to the marriage. Justin I even went so far as to amend the laws (senators, which Justinian was, could not marry actresses) in order to permit the marriage and to legitimise Theodora's illegitimate daughter. Procopius also claims there was an illegitimate son, too, but no other sources substantiate this.

The Empress, 20 years younger than her husband, is described by Procopius as being short but attractive, a stickler for court ceremony, and a lover of luxury. Theodora was crowned as empress in the same coronation ceremony as her husband on 1 April 527 CE. Justinian had insisted his wife be crowned as his equal and not as his consort. The pair also matched each other in intelligence, ambition, and energy, and with their lavish coronation in the Hagia Sophia, they seemed to herald a new era for the Byzantine Empire and its people.

The Nika Revolt

Theodora's active role in Byzantine politics and the staunch support she gave her husband are best revealed by the incident of the Nika Revolt of 11-19 January 532 CE. This was an infamous riot caused by factions of the supporters in the Hippodrome of Constantinople. The real causes for complaint were Justinian's tax hikes (to pay for his incessant military campaigns) and his general autocracy, but the riot was sparked by the emperor's refusal to pardon Blue and Green supporters for a recent outburst of violence in the Hippodrome.The troublemakers joined forces for once, and using the ominous chant “Conquer!” (Nika), which they usually screamed at the particular charioteer they were supporting in a race, they organised themselves into an effective force.

The trouble began with Justinian's appearance in the Hippodrome on the occasion of the opening races of the games. The crowd turned on their emperor, the races were abandoned and the rioters spilt out of the Hippodrome to rampage through the city. They left an impressive trail of destruction wherever they marched, burning down the Church of Hagia Sophia, the Church of Saint Irene, the baths of Zeuxippus, the Chalke gate, and a good portion of the Augustaion forum including, significantly, the Senate House. The starting point of all this destruction, the Hippodrome, escaped with only minor damage. The riot had become a full-scale rebellion and Hypatios, the general and nephew of Anastasius I (r. 491-518 CE), was crowned in the Hippodrome as the new emperor by the rioters.

Justinian was not to be so easily pushed from his throne, although it is Theodora who is credited with persuading the Emperor not to flee the mob but stand firm and fight. Her words at that crucial moment were recorded by Procopius as follows:

I do not care whether or not it is proper for a woman to give brave counsel to frightened men; but in moments of extreme danger, conscience is the only guide. Every man who is born into the light of day must sooner or later die; and how can an Emperor ever allow himself to become a fugitive? If you, my Lord, wish to save your skin, you will have no difficulty in doing so. We are rich, there is the sea, there too are our ships. But consider first whether, when you reach safety, you will not regret that you did not choose death in preference. As for me, I stand by the ancient saying: royalty makes the best shroud. (quoted in Brownworth, 79-80)

The imperial cause was greatly helped by the gifted generals Belisarius and Mundus, who ruthlessly quashed the revolt by slaughtering 30,000 of the perpetrators inside the Hippodrome. Hypatios, who had not actually wished to be crowned by the rioters, was executed nonetheless. No games were held in the Hippodrome for several years after the crisis, but one happy consequence of the whole destructive episode was the required rebuilding programme which resulted in the construction of the present version of the Hagia Sophia church.

Attitude to the Church

Theodora's religious policies seem to have been entirely her own, they were certainly not those of her husband, the leader of the Byzantine church and protector of orthodoxy. The Empress favoured Monophysitism, that is the belief that Jesus Christ had only one, divine nature (physis), which went against the orthodox view that he had two natures - one human and one divine. Nor were her views merely theoretical ponderings, for Theodora acted upon them and protected and housed priests and monks who adhered to monophysite beliefs, even using the Great Palace of Constantinople to do so. Indeed, the Empress is credited with the promotion of, and ultimately achieving the adoption of, Monophysitism in Nubia around 540 CE.

Political Intrigues

Theodora's political manoeuvres are blamed for the downfall of the chief minister John of Cappadocia, although he was none too popular with the Byzantine people either because he was seen as the instigator of the oppressive tax reforms which had caused the Nika Revolt. Procopius, too, paints the finance minister as a paradigm of corruption and debauchery. John was dismissed after the revolt as one of the demands of the rioters but he later made a political comeback. It was then that Theodora was said to have conspired against him out of personal hatred. John was thus banished from court in 541 CE.

Other victims of the Empress' machinations were Pope Silverius (deposed in 537 CE) and possibly the Gothic queen Amalasuntha, who was assassinated, but real details and hard evidence are lacking. Belisarius was another who found himself in Theodora's bad books. He might have been a great general, perhaps Byzantium's greatest, but his success only aroused the suspicions of the empress, who may well have coloured her husband's dealings with his foremost commander, which resulted in a lack of material support in the field of battle when needed.

Worse was to follow for Belisarius when the devastating bubonic plague struck the empire in the spring of 542 CE. Justinian himself was infected; he survived, but while he was gravely ill, Theodora ruled alone. Seeing that if her husband died, and with no heir to play regent for, her position would be untenable, the Empress moved quickly against the general she regarded as her greatest rival for the throne. Belisarius was too popular a figure to simply imprison or murder but he could be cut down a peg or two, and so Theodora ordered he be relieved of his command and his property be confiscated. Fortunately for the general, when Justinian recovered the following year and with the Moors and Goths baying at the frontiers of the empire, he was restored to his former position.

Procopius also states that the Empress was not slow to place her own friends and associates in positions of power at court. Besides these darker tales of personal vendettas and cronyism, Theodora was noted for her influence on Justinian's social reforms and her charitable work, sponsoring the foundation of many institutions for the poor such as orphanages, hospitals, and (perhaps significantly given her former profession) a home for former prostitutes seeking to reenter respectable society.

Death

Theodora died in 548 CE, aged just 51 or 52, probably of cancer. Justinian had no heir but, perhaps significantly, he never remarried. Theodora's daughter from before her marriage to Justinian had three sons and all of these became prominent figures in the Byzantine court. Justinian, after a period a deep mourning, would rule for another 17 years but he never seemed quite so focused or as brilliant as when he had had Theodora by his side.

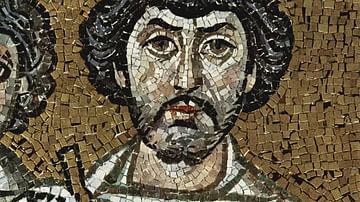

Procopius might have stolen the accolades for most-lasting and colourful literary portrait of the Empress but, in the visual arts, there is a formidable rival to how Theodora is remembered in history. This most celebrated of depictions is in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. The glittering wall mosaic shows the Empress in one panel while another shows Justinian and the archbishop of Ravenna, Maximian (r. 546-556 CE). Theodora, like her husband, is portrayed with a large halo. She is also wearing a great deal of jewellery with necklaces, earrings, and a fabulous gem-studded crown, and a Tyrian purple robe. She presents to the church a jewelled gold chalice and is surrounded by officials and her extensive entourage of court ladies.