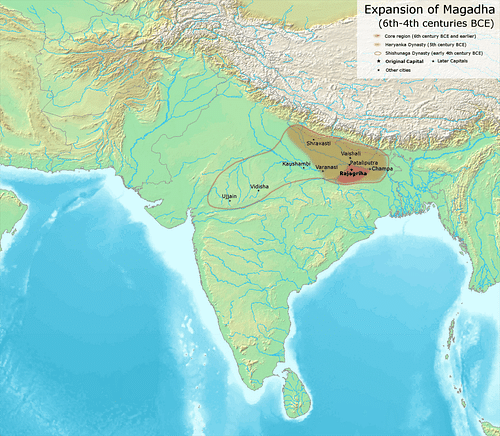

In ancient India from the 6th century BCE onwards, the kingdom of Magadha (6th century BCE to 4th century BCE) made a mark for itself. Located in the eastern part of India in what is today the state of Bihar, it outshone other kingdoms and republics when it came to territorial expansion and control, which was the main reason and context for its incessant wars. The period of expansion and wars started from the reign of Bimbisara (543 BCE) and lasted until the fall of Dhanananda (322/321 BCE), when the Mauryans took over.

Along with Bimbisara, the main Magadha actors who screamed war were his son Ajatashatru (492 BCE - 460 BCE) and the kings Shishunaga (c. late 5th century BCE) and Mahapadma Nanda (about mid-4th century BCE). The Magadhan armies under these aggressive rulers fought pretty much like any other kingdom's army in ancient India, using the prevalent four-fold army system (chariots, infantry, cavalry and elephants), personally led by kings or princes. Forts were present and thus, siege warfare was resorted to. In many cases, intrigue was used as a means of war. The able royal leadership and the drive to expand territorially was the main reason for Magadhan success as it impacted heavily on its military system and modes of warfare. The kingdom fell when the king was weak and unpopular and his supporters lost to intrigue—it was not exactly a military defeat. Interestingly, the story of Magadhan expansion reads just like a story—complete with intrigues, scandals, murders, undercover operations and whatnot. Interestingly, it is all history.

Political Setting

Magadha was one of 16 territorial units termed as mahajanapadas, which included both kingdoms and republics. Anga, Koshala (Kosala), Avanti and Vriji were those mahajanapadas geographically close to Magadha, against which this kingdom was to wage its wars. The Vriji or Vajji, was a confederacy of many clans of which the Lichcchavis were predominant. The capital was at Vaishali and it was governed by an oligarchy composed of a governing body of 7707 members, styled raja (king). Coming from different mahajanapadas, most of the royal actors in this story of expansion were contemporaries of the Buddha and had interacted with him.

Wars & Expansion under the Haryanka Dynasty

King Bimbisara

Geographically, the kingdom of Magadha had many advantages, especially in military terms. It was protected on all sides by mountains and rivers. The capital Girivraja was enclosed by five hills and stone walls. Trade and agriculture were thriving, thus providing an excellent resource base for military expeditions. A new capital Rajagriha (Sanskrit: “royal home”) developed around Girivraja and continued to be the royal home till the shift to Pataliputra.

King Bimbisara (543 – 492 BCE), who was also known as Shrenika or Seniya, was the son of King Bhattiya, the first king of the Haryanka dynasty. Crowned at the age of 15, he was credited with beginning Magadha's territorial expansion. His quest, or rather, his decision to go to war, was built upon Magadha's advantages as compared to its adversaries. Bimbisara first annexed Anga to the east. One of his sons Ajatashatru participated in the war with Anga. Pleased with his bravery and leadership, Bimbisara made him the viceroy upon its conquest.

However, his kingdom was not strong enough to conquer heavyweights like Koshala and Vaishali. So, Bimbisara chose a bloodless way out—he entered into matrimonial alliances with Koshala and Vaishali. From Koshala, the village of Kashi was received in the form of dowry, which yielded high revenues. Ultimately, the territory of Bimbisara came to consist of 80,000 villages and an area of 300 leagues.

King Ajatashatru

King Bimbsiara's successor Ajatashatru (Sanskrit: “One whose enemies are not born”; Pali: Ajatasattu; also known as Kunika) carried on further with the schemes of expansion. His reign lasted from 492 BCE to 460 BCE. His enemies may not have been born, but were definitely created. The first on the list (according to him) was his own father, whom he deposed, imprisoned and later killed, for fear that the throne might be given to any of his half-brothers. This act brought upon Ajatashatru's first war as king. King Prasenajit (Pali: Pasenadi) (c. 6th century BCE) of Koshala decided to avenge the deaths of his brother-in-law and sister, who had died of grief at Bimbisara's tragic demise. In this endeavour, he was joined by some republican mahajanapadas bordering Magadha in the north and northwest, like the Vrijis of Vaishali and Mallas of Kushinagara and Pava.

The fortress of Pataligrama was built by Magadha in defence, which within a generation developed into the city of Pataliputra, the capital of empires in India for centuries to come.

Ajatashatru used both strategy and military means to deal with his opponents. The war with Koshala began after Prasenajit took hold of Kashi and stopped its revenues from going to Magadha. The loss of revenue and loss of face made Ajatashatru prepare for a fitting reply on the battlefield. Fortune favoured both sides, with the war not coming to any conclusion for a long time, but ultimately, Magadha prevailed. Koshala humbled, Prasenajit returned Kashi (which became a part of Magadha) and offered his daughter in marriage to the conqueror.

Conquest of Vaishali: War by Other Means

The war with Vaishali did not prove to be a cakewalk. In need of advice, Ajatashatru decided to send a minister to seek the counsel of the wisest man living at the time—the Buddha. He stated that the Vrijis could not be conquered, as they were observing all conditions that strengthen a republic, including holding assemblies and unity of counsel and policy. Taking note of the issue of Vrijian unity, Ajatashatru decided to break it first before he did anything else. He had already noted that a unified enemy implied heavy resistance and resultant heavy losses.

As advised by one of his ministers, Varshakara (Pali: Vassakara), the Magadhan monarch pretended to have him disgraced and banished, upon which the crafty ex-minister found easy asylum in Vaishali. As per plan, within a few years, he created so much dissension and disunity among the Vrijis (especially among the members of the assembly) that they could no longer agree to help each other hold off the Magadhans! With the unified defence gone, whatever was left of their resistance was wiped out by Ajatashatru's military, which had used innovative weapons called the rathamusala (a chariot with a mace attached, causing much mayhem) and the mahashilakantaga (a siege engine resembling a huge catapult). With the fall of Vaishali, the Mallas also gave in.

The accounts say that the war with Vaishali dragged on for 16 long years (484 – 468 BCE). The initial reverses received thus caused Ajatashatru to rethink his strategy and focus on breaking the Vrijis from within, while coming up with new, more radical weaponry.

The conquest in Ajatashatru's time ended with Vaishali being annexed. The accounts say that one cause of the war with Vaishali was Ajatashatru's pursuit of his fleeing brothers Halla and Vehalla, They had taken with them certain prized objects and had been given shelter by the Lichchhavis who refused to surrender them. Whatever the case, political ambition was clearly dominating Ajatashatru's mind. He had after all, not deposed (killed!) his father for nothing, and had conveniently ignored his father's cordial and family relations with Koshala and Vaishali (according to the accounts, his own mother, Bimbisara's second wife, was the daughter of one of the chieftains of Vaishali). It is highly likely that even if war had not erupted in his face, Ajatashatru would have actively sought it.

A major characteristic of the wars waged by Ajatashatru were that both were long-drawn-out affairs, with no quick conclusions or no single decisive battlefield victory that could decide the outcome of the war. This also points to the military capabilities of his opponents, and that at this time, Magadha was not militarily superior. This superiority was slowly, and painfully, built.

Ajatashatru also began fortifying his capital against an invasion from Avanti, which did not happen. His son Udayin (aka Udayi or Udayibhadra), who succeeded him in 459 BCE, fought with Avanti, but not many details are available. Earlier, he had founded the strategically situated city of Pataliputra. The last rulers of this dynasty were not so efficient and the last was ultimately replaced by a new dynasty of the Shaishunagas.

Wars & Expansion under the Shaishunagas & Nandas

The first king, Shishunaga(c. late 5th century BCE), continued the forward policy by absorbing Avanti, thereby ending its dynastic rule of the Pradyotas (which were not heard of again in Indian history). This victory handed to Shishunaga the territories of Madhyadesha, Malwa and many others in North and Central India, and removed the only serious enemy it had at the time.

The last ruler of this dynasty was murdered, and with no credible succession to take place, a new king called Mahapadma Nanda took over about the middle of the fourth century BCE, ushering the reign of the last dynasty before the Mauryans took over the reins of power in Magadha.

Pali works refer to Mahapadma as Ugrasena because of his huge army. His conquests enabled Magadha to stretch its boundaries much further (Koshala was annexed), with the result that by the time of Dhanananda (329 - 322/21 BCE), the last ruler of the dynasty, the kingdom possessed a vast treasure, and an army numbering 20,000 cavalry, 200,000 infantry, 2,000 chariots and 3,000 elephants, as according to the Roman historian Curtius (1st century CE).

Dhanananda was a contemporary of Alexander the Great (356 - 323 BCE), who invaded India in 326 BCE and was known to the Greeks as Xandrames or Agrammes. It was the knowledge of this Magadhan might that had added to the despair of the already war-weary Macedonian troops in India's northwest, forcing them, among other reasons, not to press further into India.

Magadha's expansion was to resume under the Mauryas after Chandragupta Maurya (322/21 - 297 BCE) overthrew Dhanananda. The Kingdom of Magadha thus laid the foundation of India's first subcontinental empire.

Magadha Decline

The Nanda rule ended about 322 – 321 BCE. Dhanananda's mighty army and power could keep his critics in check, but do nothing to improve his popularity among his subjects (who had issues with heavy taxation and the personality of the ruler). However, a scholar called Vishnugupta Chanakya or Kautilya (c. 4th century BCE) decided to take radical action in order to avenge his humiliation at the hands of the king.

He enabled his protégé Chandragupta Maurya (Sandrakottos to the Greeks) to raise a huge and formidable army and challenge Nanda authority. Dhanananda lost, and it is quite interesting to see how. No matter what Chandragupta's military might was, there were (again!) lots of intrigues, counter-intrigues, plotting and counter-plotting which Kautilya resorted to in order to break the strength of Dhanananda by weaning away his key allies, loyalists and supporters. The Sanskrit drama Mudrarakshasa, written by Vishakhadatta somewhere between the 4th and the 8th centuries CE (presumably 5th century CE) gives vivid details of the same.

Chandragupta took over the throne at Pataliputra and became the first Maurya ruler. With Dhanananda's popularity ratings being abysmal, the new king (and later emperor) was happily accepted. The kingdom of Magadha had passed into history.

Warfare in the period

Army Organization

The Magadha army was composed of four arms (chaturanga):

- infantry

- cavalry

- chariots

- elephants

They were all deployed in the field of battle in formation, as decided by the commanders, based on factors such as the nature of the terrain and the composition of one's own and the enemy's forces. Great concern was shown to the training of men and animals. Sham fights would be organized and the army deployed in battles which were then reviewed.

The kings and princes were well-trained in the arts of war and leadership. They were expected to display courage and often personally led their armies and participated in the defence of forts. The Buddhist texts mention Prasenajit capturing Ajatashatru after Magadha lost a battle, but then setting him free, believing that he would call off hostilities (he, of course, went the whole mile till he won).

The senapati or the commander of the army was the most important military official after the king. The chief ministers also occasionally marched with the army.

The army was a standing one, i.e., recruited, trained and equipped by the state. The body of officials known as mahamatras ran the department of war. There are references to spies, local guides, labour and even naval developments. The last would have been useful to Magadha due to the rivers which surrounded or flowed through it.

Divisions of the Army

Infantry was given importance and this was the arm where maximum numbers were concentrated. Besides the normal battle formations, the footsoldiers fought also where the other divisions of the army could not be used because of geographical limitations, i.e., in forests, hilly and inaccessible regions.

The cavalry fought as a body on the battlefield and was deployed as such. It was an important arm and princes and kings were expected to know how to handle horses. The tasks of the horsemen included cutting off provisions and reinforcements of the enemy, scouting and reconnaissance, besides charging the enemy, especially at the flanks and the rear, protecting other units of the army and covering advances and retreats and pursuing the retreating enemy.

Chariots, though used, were not as important as they had been in the earlier periods, and more stress was given to cavalry and elephants. The horses were procured from the best of places, especially northern India (the region known as Uttarapatha).

Bimbisara placed a great reliance on his war elephants to win his battles. The elephants were employed in battle in a block or a line. Otherwise, they cleared the way for marches and forded the rivers that lay in their paths, guarded the army's front, flanks and rear and battered down the walls of the enemy. However, they could frequently become uncontrollable when wounded and caused more damage than good. Yet, they remained the mainstay of Indian armies for centuries afterwards as well (compared to their advantages, the elephants' backfiring talents were quite overlooked).

Forts, Fortifications & Siege Warfare

Forts were built, attacked and defended. They had permanently stationed garrisons with a proper division of their functions. The Buddhist Pali sources give a list of such officers and troops, which include:

- billeting officers (chalaka)

- soldiers of the supply corps (pindadayika)

- stormtroopers (pakkhandino)

- warriors in leather cuirasses (cammayodhino)

The dovarika or gatekeeper was seen as an intelligent and responsible officer as he opened the gate only to trusted and well-known people, keeping out strangers and men of dubious credentials. There are references to the capital of Anga having a gate, walls and watchtower.

Weapons

The equipment of the infantry included arms as well as armour. Arms included:

- bows and arrows

- swords

- shields (often of hides)

- javelins

- lances

- axes

- pikes

- clubs

- maces

The archers did not carry any shields, as their hands were already full with bows and arrows. The Buddhist texts refer to infantrymen with arrows in their hands (sarahattha). Some of the infantrymen carried conches, drums, cymbals, horns and such other musical instruments.

A good example of the soldiers' equipment in Magadha under Nanda rule can be deduced from what ancient writers had to say about the military equipment of other kingdoms in India. With some regional difference that is quite probable, it is possible that Dhanananda's soldiers possessed similar equipment to that being used by north-western Indians who faced Alexander, as they were contemporaries.

The Greek historian Arrian (c. 86/89 – c. after 146/160 CE) gives some information here. The Indians fighting Alexander carried huge bows which were of equal length with the man who bore it, which he rested on the ground and pressed one of its ends with the left foot before releasing the arrow. The soldiers carried long bucklers of undressed ox-hide, javelins and broadswords wielded double-handed. The cavalry carried two lances and a buckler (round shield), smaller than the infantry one.

Arrian believed that even the archers carried shields, but no such evidence is given by the sculptures of Bharhut and Sanchi stupas that furnish the earliest visual evidence of a footsoldier's equipment in ancient India. Though created under Mauryan (and post-Mauryan) rule after the period under discussion, these sculptures are a good showcase of what the soldiers would have looked like in Magadha and other janapadas, since the Mauryas had succeeded the Nandas, the last Magadhan dynasty, and therefore would have carried on the same patterns of warfare and equipment as the base of their own military system, with some additions and subtractions. It is also quite probable that Magadhan archers may not have carried shields which could have been the prevalent practice in the north-west—a proof of regional differences in arms and armour within India.

Armour

In many cases, the soldiers could have been bare to the waist, owing to custom, heat or simply lack of equipment. This seems to be the case for the lowest class of soldiers, with the elites commanding the army or other officials being adequately provided for (especially with metal armour), along with some other classes of troops that could be similarly well-furnished.

But wherever they were equipped well, soldiers preferred quilted cotton jackets (owing to the high temperature in summers, it was seen as creating more comfort than metal or leather armour). Sculptures made in the Mauryan period, like those adorning the Sanchi stupa, show soldiers wearing thickly coiled turbans, often secured with scarfs tied below the chin, and bands of cloth tied across their waists and chests as protective armour.

The lower garment was a loose cloth worn as a kilt or in the drawer style (one end of the garment drawn between the legs and tucked in the waist at the back). Alternatively, metal and chainmail armour is mentioned in the literature of the Vedic and Epic periods that preceded the Magadhan conquests, and thus may have been in use at this point in time also (though not very frequently).

Different terminologies were used to denote different pieces of armour covering different body parts, i.e., shirastrana (cover for the head, including the above-mentioned turban), kanthatrana (cover for the neck), kurpasha (cover for the trunk), kanchuka (a coat extending as far as the knee joints), varavana (a coat extending as far as the heels), patta (a coat without cover for the arms), and nagodarika (gloves). There were also armours made from hides, hoofs and horns of certain animals like tortoise, rhinoceros, bison, elephant or cow.

Legacy

Magadha became the base for the imperial rule ushered in by the Mauryas (324/321-187 BCE). Being a student and later teacher at Takshashila, Kautilya was witness to the political turmoil created in north-western India because of the Macedonian invasion. This caused him to think in terms of establishing a centralized pan-Indian empire that could keep invaders at bay and restore order. The existence of numerous republics and kingdoms, disunited and perennially at war with each other, for obvious reasons, could not do so.

He considered Magadha apt to be the empire in question—his proposal for the same was met with scorn and insults from Dhanananda, which was followed by Kautilya's determination to remove the incumbent king and the eventual takeover by Chandragupta. What is important here is that Magadha was thus the only territorial entity that could provide order in the chaos. It had a virtually unrivalled military standing, crucial for the existence of the kind of empire that Kautilya wanted. Protected by its vast military, it enjoyed a stability that other kingdoms could not. Kautilya was thus determined to have Magadha as the centrepiece of his scheme of things—whether under the Nandas or someone else, it did not matter. Hence, he encouraged Chandragupta to take over.

Though Magadha was beaten less in war and more in intrigue by Kautilya, it became a redundant issue. The significant issue was the reason for the wily scholar's challenge to the Nandas. What Magadha meant was of importance and as we have seen, this in a large measure was due to the handiwork of Bimbisara and those who succeeded him. Needless to say, it was about all the wars they had waged. Their way of war and warfare provided a sound basis for the Mauryan military and its subsequent conquests. It is that legacy that became enshrined in the Arthashastra written by Kautilya, which even to this day, remains the prime text for studying the concept of war in India. It is also, unsurprisingly, a key text when it comes to understanding intrigue as a means of warfare.