The Candaces of Meroe were the queens of the Kingdom of Kush who ruled from the city of Meroe c. 284 BCE-c. 314 CE - a number of whom ruled independently c. 170 BCE-c. 314 CE - in what is now Sudan. The title Candace is the Latinized version of the term Kentake or Kandake in Meroitic and may mean “Queen Regent” or “Queen Mother” but could also mean “Royal Woman”. Although the term seems to have originally referred to the mother of the king, from around c. 170 BCE it was also used to designate a female monarch who reigned independently.

The queens making up the Candaces of Meroe were the following:

- Shanakdakhete (r. c. 170 BCE)

- Amanirenas (r. c. 40-10 BCE)

- Amanishakheto (r. c. 10 BCE–1 CE)

- Amanitore (r. c. 1-c. 25 CE)

- Amantitere (r. c. 25-c. 41 CE)

- Amanikhatashan (r. . 62-c. 85 CE)

- Maleqorobar (r. c. 266-c. 283 CE)

- Lahideamani (r. c. 306-c. 314 CE)

A “Candace, queen of the Ethiopians” is mentioned in the Bible when the apostle Philip meets “a eunuch of great authority” under her reign and converts him to Christianity (Acts 8:27-39). In this passage, as in other ancient works mentioning the Candace, the royal title has often been confused with a personal name.

Prior to c. 284 BCE, kings ruled Kush from Meroe but the king Ergamenes (also known as Arkamani I, r. 295-275 BCE) instituted a number of reforms and among these seems to be the elevation of royal women to the position of queen. The title “Kentake” appears prior to Ergamenes' reign but there is no evidence of women reigning alongside a king – only of a royal woman who was the king's mother; following his reign, however, the title often refers to a female monarch. Male rulers follow Ergamenes in succession and seem to have had queens who co-ruled or exerted significant influence, but the queen Candace Shanakdakhete (r. c. 170 BCE) reigned independently and so did a number of women after her.

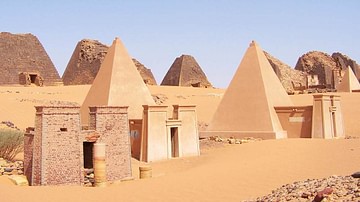

Meroe flourished as the capital of the Kingdom of Kush between c. 750 BCE – 350 CE and became legendary as a city of fabulous wealth. Located on the Nile in the region of modern-day Sudan, Meroe grew rich from trade and its ironworks and abundant grain supply ensured a steady production of goods others wanted and needed; but it was the monarchy, periodically controlled by women, that established and maintained the trade which encouraged such affluence.

The city began to decline due to overuse of the land and resources and had already passed its peak when it was invaded by the Axumites (from the Kingdom of Axum, located in present-day Ethiopia/Eritrea) in c. 330 CE and sacked. It was abandoned 20 years later c. 350 CE and the title of Candace vanishes from the historical record afterwards.

The Rise of Meroe & Ergamenes

Meroe was originally an administrative center south of the Kushite capital city of Napata. In 590 BCE Napata was sacked by the Egyptian king Psammeticus II (r. 595-589 BCE) and the capital was moved to Meroe. Napata had been heavily influenced by Egyptian culture and religion – as the entire Kingdom of Kush was initially – due to close contact through trade and Egypt's repeated military campaigns in the region. This same paradigm was held to at Meroe where official documents were written in Egyptian, the gods who appeared in the temples were Egyptian, art was created in Egyptian styles, kings were depicted as Egyptian pharaohs, and their tombs were pyramids.

The city was already thriving before it became the capital of Kush, but afterwards its wealth would become legendary. Large fields yielded abundant crops which were easily transported up and down the nearby Nile in trade. Hunters stalked prey such as leopards and elephants whose skins and tusks were then traded upriver to Egypt. The principal industry, however, was ironworking and Meroitic tools and weapons became highly sought after and commanded a high price.

The kings of the city regulated trade and it is possible that they followed a model similar to Egypt's in which taxes and money from trade went to the government which then provided resources to the people. The iron industry boomed not only because of the expert craftsmen in the city but also the abundant natural resources of the enormous forests surrounding Meroe. Wood was required for the furnaces to smelt the iron and also in the production of charcoal and these furnaces burned hot on a daily basis. Scholar Kevin Shillington notes:

To this day, huge mounds of waste slag from their smelting furnaces rise up alongside the modern railway to bear witness to the enormous iron output of the ancient kingdom of Meroe. Iron provided the farmers and hunters of Meroe with superior tools and weapons. The development and use of iron was thus partly responsible for the very success, growth, and wealth of the Meroitic kingdom. (44)

When Ergamenes came to the throne in 295 BCE, Meroe had already been prospering for centuries but his reforms would only improve upon the city's success. According to the historian Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE), Ergamenes had studied Greek philosophy and was not inclined to blindly follow the religious traditions of his people. Among these traditions was the practice of the priests of Amun choosing the monarch, setting a span for that monarch's reign, and deciding when the king should die for the good of the people and make way for a successor.

The cult of Amun had been a powerful political force in Egypt for millennia and exerted the same kind of influence over the kings of Kush. At Napata, in fact, the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III (r. 1458-1425 BCE) built the temple of Amun which would become the most important religious site in the kingdom for centuries. As in Egypt, the priesthood seems to have been tax-exempt and so were able to accrue significant wealth and influence.

Ergamenes broke the priests' power through direct action, not legislation, by arriving at the temple at Napata with an armed force and slaughtering them all. He then discarded the tradition of the priesthood's influence over the king, though maintaining the cult of Amun, and initiated further reforms to distance Meroe from Egyptian influence.

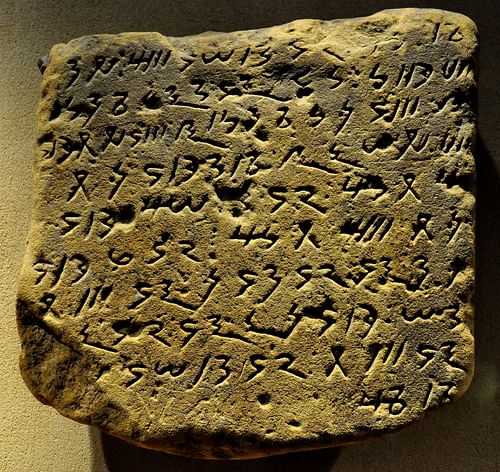

The gods, though still bearing some evidence of Egyptian culture, begin to appear as indigenous deities during his reign. Pyramids take on a uniquely Meroitic style of architecture. Kings and their queens appear in Meroitic attire and the art of the period shifts away from Egyptian to a distinctly indigenous style. Most importantly, Egyptian hieroglyphics disappear during Ergamenes' reign to be replaced by Meroitic script. This reform is significant because this script has not yet been deciphered and, because of this, the history of the latter centuries of the Kingdom of Kush is obscured.

It is clear that Kush had armies but very little is known about their organization. There was obviously a strong central government but daily administrative practices and even the process of succession is unclear. Trade flourished but precisely how it was conducted is unknown. The names of the rulers of Meroe and their probable reigns were pieced together by the archaeologist George A. Reisner (1867-1942 CE) who excavated Napata and Meroe and whose conclusions are still accepted for the most part but, even so, there are gaps and contradictions in his narrative which could only be resolved by a written history of the culture.

It is this lack of such a history which makes a discussion of the Candaces of Meroe so challenging. It appears that the practice in Meroe was that the brother of the king succeeded him, not the king's son, and yet the title of Candace seems to have originally referred to the king's mother which, according to scholar Derek A. Welsby, designates “the mother of the crown prince, i.e. the mother of the next king” (26). Since a Candace was also the wife of a reigning king this interpretation would mean that a king's son would succeed him and yet this does not seem to be the case. Welsby writes:

The evidence we have suggests that, even with a `legal' succession, there were no hard and fast rules for the choice of the next monarch and this can only have led to confusion and potential or actual conflict during the transfer of power. (27)

Whether there was such conflict, however, is far from clear. Evidence suggests continuing tension between the throne and temple, and possibly between successors, but no consensus can be reached on its interpretation. It may be that the erasure of names and destruction of certain monuments was due to conflict in dynastic succession or to the priests trying to reassert their power but just as easily may not have anything to do with either. It is also unknown exactly how much influence a queen in Meroe had prior to Ergamenes' reign; all that is known for certain is that after his reign some female rulers wielded considerable power and Meroe flourished accordingly.

The Candaces of Meroe

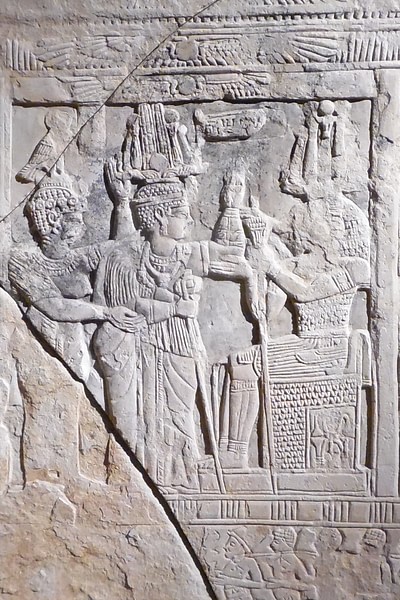

Shanakdakhete (r. c. 170 BCE): The first queen to rule independently was Shanakdakhete (also given as Shanakdakheto) who appears in battle dress leading her armies. Under her reign, Meroe expanded its borders and the economy boomed. She may have performed a religious-political function along the lines of the position of God's Wife of Amun in Egypt (the female counterpart to the High Priest of Amun). Her adherence to Egyptian traditions is evident in her inscriptions where she refers to herself as “Son of Ra, Lord of the Two Lands, beloved of Ma'at” which is a common Egyptian designation. She is depicted with a young man, clearly a crown prince, who may be her successor Tanyidamani (dates unclear) but this is speculation. It is also unclear whether Tanyidamani even was her successor.

Amanirenas (r. c. 40-10 BCE): Amanirenas is best known as the queen who won favorable terms from Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE-14 CE) following the conflict known as the Meroitic War (27-22 BCE) between Kush and Rome. The war began in response to Kushite raiding parties making incursions into Roman Egypt. Rome had annexed Egypt as a province following the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and it quickly became one of the new empire's most critical territories as it supplied Rome with an abundance of grain. The Roman prefect of Egypt, Gaius Petronius responded to the raids by invading Kush around 22 BCE and destroying the city of Napata. Amanirenas was in no way cowed and retaliated with further aggression. She is depicted as a courageous queen, blind in one eye, and a skilled negotiator. Following the conflict, her control of the terms is evident in Rome's respect in the peace talks and an increase in trade between Rome and Meroe. Amanirenas had captured a number of statues from Egypt, among them many of Augustus, which she returned following the peace; but the head of one she buried under the steps of a temple so that people would walk over Augustus in their daily visits. This is the famous Meroe Head now housed in the British Museum.

Amanishakheto (r. c. 10 BCE–1 CE): Little is known of Amanishakheto outside of her lavish grave goods of ornate jewelry. Her tomb was among the many in Meroe broken into and destroyed by the notorious treasure hunter Giuseppe Ferlini (1797-1870 CE) who had no interest in history or preservation and was only seeking gold and artifacts he could sell for a high price. Ruined inscriptions and reliefs from her tomb show her as a powerful queen who ruled independently but details of her reign have been lost.

Amanitore (r. c. 1-c. 25 CE): Amanitore reigned over the most prosperous period of Meroe's history. She was able to rebuild the Temple of Amun at Napata and renovated the large temple to the god in Meroe. Trade was at its height as evidenced by grave goods and other artifacts from the period and the iron industry and agriculture flourished as attested to by the amount of waste slag and improved irrigation canals dug during this time. She is depicted with her co-ruler King Natakamani but it is unclear if he was her husband or son and it seems she reigned alone later. She is depicted on her temple wall at Naqa conquering her enemies as a warrior queen. She may be the Candace referenced in Acts 8:27 of the Bible (mentioned at the start of this article) but this is contested; it is more likely that queen was Amantitere.

Amantitere (r. c. 25-c. 41 CE): Amantitere is the queen most often identified as the Candace in Acts 8:27. It has been suggested that she may have been Jewish only based on the passage in the Bible in which her eunuch, encountered by the apostle Philip, is reading the Book of Isaiah. There is no evidence in Meroe itself which supports the existence of a Jewish community but such communities did exist throughout Kush in small numbers. The biblical passage has also been cited to prove that Amantitere ruled alone since it states her eunuch had “great authority” and was in charge of her treasury but those statements hardly prove an autonomous queen any more than the eunuch's reading of Isaiah argues for her Judaism. Nothing is known of her reign but physical evidence from the period shows a high degree of affluence.

Amanikhatashan (r. c. 62-c. 85 CE): Nothing is known of her reign except for the military aid she provided to Rome during the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 CE. She sent Kushite cavalry but most likely also sent archers since the Kushite archers were legendary for their skill. One of the early Egyptian names for the region of Kush, in fact, was Ta-Sety (“The Land of the Bow”) for this reason. Nothing else is known of her reign but, like other later Candaces, she was most likely associated with the Egyptian goddess Nut as a High Priestess. Nut was the sky goddess who personified the canopy of the heavens and was mother to the primary deities Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus the Elder. Although Egyptian script fell out of use during Ergamenes' reign, Egyptian gods such as Amun, Nut, and others continued to be venerated. It is possible, though far from clear, that Amanikhatashan would have served as the most powerful religious figure in Meroe as priestess of Nut.

Maleqorobar (r. c. 266-c. 283 CE) and Lahideamani (r. c. 306-c. 314 CE): Nothing is known of the reigns of these two queens. They are known to have ruled over Meroe during its decline but no other details have come to light. Meroe's wealth and prestige began to wane c. 200 CE when Rome elevated the Kingdom of Axum in Ethiopia to its primary partner in trade and Meroe was slighted. Exactly why Rome chose this course is unclear but part of the reason could have been the overuse of the land surrounding the city which depleted its resources. The forests had been used up in supplying fuel for the iron industry and the fields were depleted of nutrients through steady farming and overgrazing of livestock. In c. 330 CE Meroe was invaded by Axum, most likely under their king Ezana, and sacked; it was deserted c. 350 CE.

Conclusion

In 1834 CE, when Giuseppe Ferlini looted the treasures of Meroe he could find no buyers because the European market refused to believe that a black African kingdom had produced such incredible works. Egypt had long been “whitewashed” and was considered distinct from kingdoms to the south such as Kush which was associated with black Africa. Since it was mentioned in the Bible, Egypt, like Palestine, was routinely depicted as having been inhabited by white people by Europeans and Americans who had grown comfortable worshipping a white Jesus and honoring a white Moses but they never saw the need to extend this perceived “whiteness” all the way down the continent of Africa.

Almost one hundred years later, when George A. Reisner excavated Meroe, he concluded that the ruling class of Meroe were light-skinned people reigning over the “ignorant” black population who were elevated only by their monarchs exposing them to Egyptian culture. Reisner concluded this for the same racist reasons the white Europeans of Ferlini's time dismissed his artifacts. Even in the mid-20th century CE it was inconceivable to the scholarly community that a black-skinned people could have created a civilization such as the Kushite Kingdom of Meroe.

This same paradigm has been followed regarding the female rulers of that kingdom. It has been suggested that the Candace was a co-ruler with a male king and instances of a woman ruling alone are simply cases of a regent holding the throne for her son. This type of scenario is certainly possible - as noted, the Meroitic script has not been deciphered and the history of Meroe is far from clear - but in respect to the monarchy it seems quite apparent that women not only ruled but enabled the kingdom to prosper. The Candaces of Meroe, in fact, are among the most powerful and successful monarchs of the Kingdom of Kush and their skill in leadership was the equal, or better, of any king.