The Second Crusade (1147-1149 CE) was a military campaign organised by the Pope and European nobles to recapture the city of Edessa in Mesopotamia which had fallen in 1144 CE to the Muslim Seljuk Turks. Despite an army of 60,000 and the presence of two western kings, the crusade was not successful in the Levant and caused further tension between the Byzantine Empire and the west. The Second Crusade also included significant campaigns in the Iberian peninsula and the Baltic against the Muslim Moors and pagan Europeans respectively. Both secondary campaigns were largely successful but the main objective, to free the Latin East from the threat of Muslim occupation, would remain unfulfilled, and so further crusades over the next two centuries would be called, all with only marginal successes.

Goals

Edessa, located on the edge of the desert of Syria in Upper Mesopotamia, was an important commercial and cultural centre. The city had been in Christian hands since the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE) but it fell to Imad ad-Din Zangi (r. 1127-1146 CE), the Muslim independent ruler of Mosul (in Iraq) and Aleppo (in Syria), on 24 December 1144 CE. Following the capture, which Muslims described as "the victory of victories" (Asbridge, 226), western Christians were killed or sold into slavery while eastern Christians were permitted to remain. A response was called for. The Christians of Edessa had appealed for help, and a general defence of the Latin East, as the Crusader states in the Middle East were collectively known, was required.

Pope Eugenius III (r. 1145-1153 CE) formally called for a crusade (what is now known as the Second Crusade) on 1 December 1145 CE. The goals of the campaign were put somewhat vaguely. Neither Edessa nor Zangi was specifically mentioned, rather it was a broad appeal for the achievements of the First Crusade and Christians and holy relics in the Levant to be protected. This lack of a precise aim would have repercussions later in the Crusaders' choice of military targets. To boost the Crusade's appeal, Christians who joined were promised a remission of their sins, even if they died on the journey to the Levant. In addition, their property and families would be protected while away and such trivial matters as interest on loans would be suspended or cancelled. The appeal, backed by recruitment tours across Europe - notably by Bernard, abbot of Clairvaux - and the widespread public reading of a letter from the Pope (called the Quantum praedecessores after its first two words), was hugely successful, and 60,000 Crusaders made ready for departure.

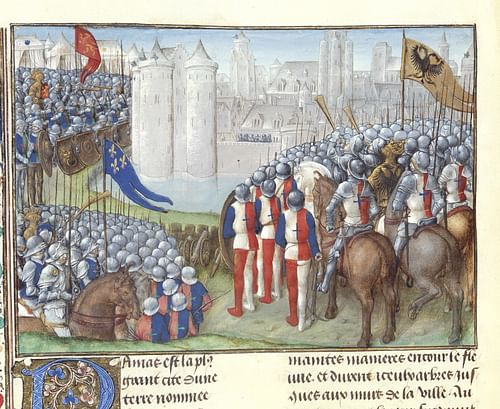

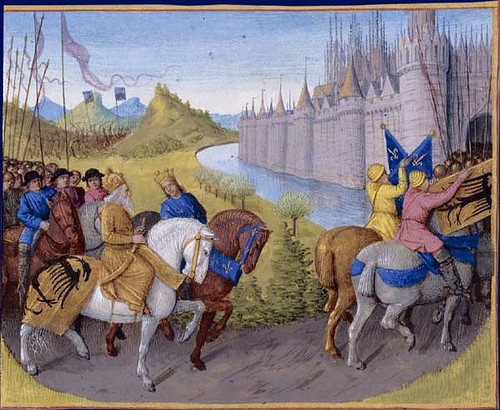

The Crusade was led by the German king Conrad III (r. 1138-1152 CE) and Louis VII, the king of France (r. 1137-1180 CE). It was the first time that kings had personally led a crusader force. In the early summer of 1147 CE the army marched across Europe to Constantinople, and from there to the Levant where the French and German troops were joined by Italians, northern Europeans, and more French crusaders who had sailed rather than travelled by land. The Crusaders were reminded of the urgency of a military response when Nur ad-Din (also spelt Nur al-Din, r. 1146-1174 CE), Zangi's successor after his death in September 1146 CE, defeated the Latin leader Joscelin II's attempt to retake Edessa. Once again the city was sacked to celebrate Nur ad-Din's new power. All the Christian male citizens of the city were slaughtered, and the women and children were sold into slavery, just as their western fellows had been two years before.

Iberia & Baltic Campaigns

The Second Crusade, besides Edessa, had additional objectives in Iberia and the Baltic, and both campaigns were backed by the Pope. The crusaders who were to sail to the east were perhaps used in Iberia because they had to delay their departure in order for the land armies to make their slow progress to the Levant. The sea route was much quicker and so it was advantageous to put them to good use in the meantime. A fleet of some 160-200 Genoese ships packed with crusaders sailed for Lisbon to assist King Alfonso Henriques of Portugal (r. 1139-1185 CE) capture that city from the Muslims. On arrival, a textbook siege began on 28 June 1147 CE and was ultimately successful, the city falling on 24 October 1147 CE. Some crusaders successfully continued the war against the Muslims in Iberia, the reconquista, as it was known, notably capturing Almeria in Spain (17 October 1147 CE) guided by King Alfonso VII of León and Castille (r. 1126-1157 CE) and Tortosa in eastern Spain (30 December 1148 CE). An attack on Jaén in southern Spain, though, was a failure.

Another arena for the Crusades was the Baltic and those areas bordering German territories which continued to be pagan. The Northern Crusades campaign, conducted by Saxons led by German and Danish nobles and directed against the pagan Wends, provided a new facet to the Crusader movement: active conversion of non-Christians as opposed to liberating territory held by infidels. Between June and September of 1147 CE, Dobin and Malchow (both in modern northeast Germany) were successfully attacked but the overall campaign fared little better than the usual annual raiding parties sent into the area. The Baltic would continue to be an arena for Crusades in the following centuries, especially with the arrival of the Teutonic Knights from the 13th century CE.

The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine emperor at the time of the Second Crusade was Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143 - 1180 CE). Unlike his predecessors, Manuel seemed greatly attracted to the west. He favoured Latins in Constantinople, dispensing civil awards and military titles in their direction. Ever since the First Crusade, though, there was a deep suspicion on both sides between the west and Byzantium. Manuel's primary concern was that the Crusaders were really only after the choice parts of the Byzantine Empire, especially now that Jerusalem was in Christian hands. It was for this reason that Manuel insisted the leaders of the Crusade, on arrival in September and October 1147 CE, swear allegiance to him. At the same time, the western powers considered the Byzantines rather too preoccupied with their own affairs and unhelpful in the noble opportunities they thought a crusade presented. The Byzantines had been attacking Crusader-held Antioch, and the old divisions between the eastern and western churches had not gone away. It was significant that Manuel, despite the diplomacy, strengthened the fortifications of Constantinople.

In more practical terms, the usual rabble of zealots and men of dubious background seeking absolution which crusader campaigns seemed to attract were soon pillaging, looting, and raping as they crossed Byzantine territory on their way to the Levant. This was despite Manuel's insistence to the leaders that all food and supplies be paid for. Manuel provided a military escort to see the Crusaders on their way as quickly as possible, but fighting between the two armed groups was not infrequent. Adrianople in Thrace suffered particularly badly.

When the French and German contingents arrived at the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 1147 CE, things worsened still. Always suspicious of the Eastern Church and now outraged to discover Manuel had signed a truce with the Turks (seen by him as less of a threat than the Crusaders in the short term), the French section of the army wanted to storm Constantinople itself. The German crusaders had their own problems, a large number of them being wiped out by a terrible flash flood. The Crusaders were, eventually, persuaded to hurry on their way east with reports of a large Muslim army preparing to block their path in Asia Minor. There they ignored Manuel's advice to stick to the safety of the coast and so met disaster.

Asia Minor & Disaster

The German army led by Conrad III was the first to suffer from a lack of planning and not heeding local advice. Unprepared for the harsh semi-arid steppe, the Crusaders lacked food supplies, and Conrad had underestimated the time needed to reach his objective. At Dorylaion a force of Muslim Seljuk Turks, primarily archers, caused havoc with the slow-moving westerners on 25 October 1147 CE, and, forced to retreat to Nicaea, Conrad himself was wounded but did eventually make it back to Constantinople. Louis VII was shocked to hear of the Germans' failure but pressed on and managed to defeat a Seljuk army in December 1147 CE using his superior cavalry. The success was short-lived, though, for on 7 January 1148 CE the French were beaten badly in battle as they crossed the Cadmus Mountains. The Crusader army had become too stretched out, some units losing contact with each other and the Seljuks took full advantage. What remained of the westerners was commanded by a group of Knights Templars. There were a few minor victories as the Crusaders made their way to the southern coast of Asia Minor but it was a disastrous opening to a campaign which had not even reached its target of northern Syria.

The Siege of Damascus

Louis VII and his ravaged army finally arrived at Antioch in March 1148 CE. From there, he ignored Raymond of Antioch's proposal to fight in northern Syria and marched on to the south. The lack of cooperation between the two rulers, if rumours were true, may have been due to Louis' discovery that his young wife Eleanor of Aquitaine and Raymond (Eleanor's uncle) had been carrying on an affair under his very nose. In any case, a council of western leaders was convened at Acre, and the target of the Crusade was now selected, not at the already destroyed Edessa, but Muslim-held Damascus, the closest threat to Jerusalem and a prestigious prize.

Although Damascus had once been in alliance with the Crusader-led Kingdom of Jerusalem, the shifting loyalties between the various Muslim states meant this fact held no guarantee for the future and, faced with the necessity to take at least one major city or go home as complete failures, Damascus was as good a choice as any for the Crusaders. The situation was made more urgent as there was now a very real prospect that the Muslims of Damascus would join up with those of Aleppo under command of Edessa's ambitious conqueror, Nur ad-Din.

The Crusader army arrived at Damascus on 24 July 1148 CE and immediately began a siege. After only four days, though, the difficulties presented by the defences and the serious lack of water for the attackers meant the siege had to be abandoned. Once again, bad planning and poor logistics were to prove the Crusaders' undoing. The fighting around the city had been ferocious with heavy casualties on both sides but no real advance had been made. The failures of the Second Crusade were now putting the already legendary successes of the First Crusade into some perspective.

The collapse of the siege after such a short time led some, notably Conrad III, to suspect the defenders had bribed the Christian residents into inaction. Others suspected Byzantine interference. Overlooked, perhaps, is the zeal of the defenders to keep their prized possession, a city with many links to Islamic tradition, and the arrival 150 kilometres away of a large Muslim relief army sent by Nur ad-Din. With limited numbers and supplies and facing a short time limit to capture the city before relief arrived and threatened their own poor defences, the Crusader leaders may have preferred the option of retreat to fight another day. There was to be no other fight, though, as Conrad III returned to Europe in September 1148 CE and Louis, after a sightseeing tour of the Holy Land, did the same six months later. The Second Crusade, despite so much early promise, had disappointingly fizzled out like a water-damaged firework.

Aftermath

The Second Crusade was a serious blow to Byzantium's carefully constructed diplomatic alliances, especially with Conrad III against the Normans. The Crusade and Conrad's absence from Europe provided a distraction which allowed the Norman king Roger II of Sicily (r. 1130-1154 CE) the freedom to attack and pillage Kerkyra (Corfu), Euboea, Corinth, and Thebes in 1147 CE. Manuel's attempt to persuade Louis VII to side with him against Roger failed. In 1149 CE the embarrassment of a Serbian uprising and an attack on the area around Constantinople by George of Antioch's fleet was offset by the Byzantines recapturing Kerkyra. Once again, a crusade had damaged east-west relations.

Nur ad-Din, as the Crusaders no doubt had feared, continued to consolidate his empire, and he took Antioch on 29 June 1149 CE after the battle of Inab, beheading its ruler Raymond of Antioch. Raymond, the Count of Edessa, was captured and imprisoned, and the Latin state of Edessa was eliminated by 1150 CE. Next Nur ad-Din took over Damascus in 1154 CE, uniting Muslim Syria. Manuel would strike back with successful campaigns there from 1158 to 1176 CE, but the signs were ominous that the Muslims would pose a permanent threat to the Byzantines and Latin East. When Nur ad-Din's general Shirkuh conquered Egypt in 1168 CE, the way was paved for an even greater threat to Christendom, the great Muslim leader Saladin (r. 1169-1193 CE), Sultan of Egypt, whose victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187 CE would spark off the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE).