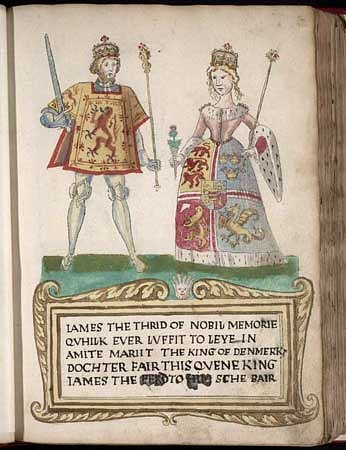

James III of Scotland reigned as king from 1460 to 1488. He succeeded his father James II of Scotland (r. 1437-1460) at the age of eight, which led to some nobles taking advantage of the king's minority and even abducting him. James was also challenged by his two brothers and again by his eldest son during a thoroughly unpopular reign which saw high taxes and systematic marginalisation of the nobility. James was killed in a skirmish with rebels in June 1488. The royal Stuart line continued with James' eldest son who became James IV of Scotland (r. 1488-1513).

Succession & Regency

James II had established strong royal control over the kingdom by eliminating or marginalising such powerful families as the Douglases, Crichtons, and Livingstons. The king even felt confident enough to attack northern England with several major campaigns through the 1450s. James' eldest son, yet another James, was born in May 1452, his mother was Mary of Gueldres (d. 1463), daughter of the Duke of Gueldres and niece of Philip the Good, the immensely powerful Duke of Burgundy. Tragedy struck the royal family when the king died in an accident on 3 August 1460. James II had been attacking Roxburgh Castle, then garrisoned by the English, and the cannon he was standing next to had exploded; he was 29 years old. Consequently, Prince James was only eight years old when he became James III of Scotland. The boy-king was crowned on 10 August at Kelso Abbey.

Queen Mary ruled as her son's regent with success, not only completing the siege of Roxburgh Castle but even managing to get back control of Berwick, a much-disputed property between Scotland and England. Mary had negotiated with Henry VI of England (r. 1422-1461 & 1470-1471) to receive Berwick in March 1461 in return for shelter as the king was just then fighting his own civil war during the dynastic conflict now known as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487). Mary also greatly improved Falkland Palace and built Ravenscraig Castle in Fife, which had battlements designed to accommodate the cannons which were fast becoming a necessity in warfare. The queen was known for her piety, and she founded Holy Trinity Church in Edinburgh, the altarpiece for which was provided by the Flemish artist Hugo van der Goes with painted panels showing James III and his queen.

Unfortunately, Queen Mary's regency was brief as she died in December 1463 and James Kennedy, Bishop of St. Andrew's, then became the king's guardian. In 1464 he ensured the young James went on two tours of his kingdom to foster grassroots support for the monarchy. Bishop Kennedy died in May 1465, which presented a long-awaited opportunity for ambitious nobles to improve their own positions at the expense of the Crown.

The King Becomes a Pawn

On 9 July 1466 James III was kidnapped while out hunting by the courtiers Alexander (keeper of Edinburgh Castle) and Robert Boyd of Kilmarnock. The Boyd brothers forced the king to pretend he was not being held against his will. Robert Boyd, the elder brother, then took the lead, sidelining Alexander and making his own son Thomas the earl of Arran. Thomas was also betrothed to Mary, the king's elder sister. Robert Boyd even convinced James to marry Margaret of Denmark (l. c. 1457-1486), the daughter of the King of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. The marriage took place on 13 July 1469, and the union would ultimately give Scotland the long-sought-after control of the Orkney and Shetland Isles. Robert Boyd, meanwhile, declared himself the Guardian of Scotland and took over the office of King's Chamberlain. When James reached maturity in 1469, both Boyd brothers got their comeuppance, and they were tried and found guilty of treason. Robert and his son managed to escape to England, but Alexander was executed.

Unpopular Policies

The king was intent on increasing royal power at any cost, a policy symbolised by his adoption of the closed imperial crown symbol and his wide application of lèse majesté, the treasonous offence of insulting the king, to include any action James considered an impediment to his will. Nobles were neglected in favour of administrators and clerics. Edinburgh became the great bureaucratic centre of government, even if the reality was that Scotland remained a kingdom that depended on its regional barons to enforce government policies across the realm. The king, however, made no effort whatsoever to visit any part of his kingdom outside the capital. In 1474 the king arranged for his eldest son and heir James (b. 1473) to marry Cecily, the daughter of Edward IV of England (r. 1461-1470 & 1471-1483). James III's pro-English stance, high taxes, and unscrupulous sale of royal pardons for cash were additional factors in his distinct lack of popularity, not only amongst his nobles but even his own family.

The king's preoccupation with music, the arts, and alchemy, became rather too much for some barons. However, to nip any rebellion in the bud, James had his two younger brothers John, Earl of Mar, and Alexander, Duke of Albany, imprisoned in 1479. John died in confinement in mysterious circumstances, seemingly bleeding to death while taking a bath. Alexander, meanwhile, escaped to the safety of France, but he would be back soon enough to stake his own claim for the throne. These developments did nothing to appease the Scottish nobles who were becoming increasingly alarmed at the king's autocracy and his preference for low-class company. Many nobles were not best pleased to see the likes of William Scheves, a former servant who once sewed the king's shirts, be given control of the archbishopric of St. Andrews. James' decision to debase the currency in 1479-80, which gave him personally plenty of silver but devastated trade, may have been the last straw. The coins might have been of questionable value but they are historically significant as the first medieval coins minted north of the Alps that show a king's portrait.

Second Kidnapping

In July 1482, perhaps not surprisingly, the king was kidnapped for a second time, this time by a group of disaffected nobles with Alexander Stuart as their figurehead. Alexander schemed with Edward IV in England to usurp his brother. An English army jointly led by Alexander and Edward's brother, invaded Scotland, the first to do so since 1400. James was captured at Lauder, north of Melrose and he was lucky to escape with his life, a fate not enjoyed by two of his entourage. The king was then imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle. It may have been the rebels' intention to make Alexander the king's regent while Edward IV saw a golden opportunity to regain control of Berwick. As it turned out, the invading army went unchallenged, and the revolution fizzled out through lack of focus and leadership. English support also vanished with the death of Edward IV in April 1483. Above all, and not for the first time, Scottish nobles baulked at the idea of murdering their king. James was released, and a fragile suspension of hostilities followed.

The respite in Scotland's turbulent politics was brief. In July 1484 a small English-Scottish force led by the Earl of Angus, the senior member of the powerful Red Douglas family, once again tried to put Alexander on the throne. Royalists defeated this force at Lochmaben on 22 July where the Earl of Angus was captured. Once again, Alexander fled south. Unwisely returning the next year, Alexander was captured and held in Edinburgh Castle until he somehow managed to escape again to France. The man who would be king was then killed in a bizarre accident in a medieval tournament in Paris, struck by a flying shard from a lance as he watched the proceedings from the stands.

Meanwhile, King James seemed unable to comprehend the connection between his harsh policies and disaffected nobility. The king carried on just as he always had, dismissing capable officials, appointing unpopular ones, and persecuting anyone he thought remotely disloyal. In February 1488 yet another attack on the king came, this time involving his son James, who declared himself the 'Prince of Scotland'. Initially, the northern barons were loyal to the Crown, but James junior had the support of the Earl of Argyll. The two sides met in a battle at Stirling that is better described as a skirmish. Small in scale, perhaps, the fate of Scotland hung on its outcome.

Death & Successor

On 11 June 1488, the small force led by the king was defeated by the rebels at Sauchieburn near Bannockburn Field. James III was carrying the great sword of Scotland's hero Robert the Bruce (r. 1306-1329), but it did not do him any good. Attempting to escape the wrath of the victors, the king was killed perhaps unintentionally or, in other versions, by an enemy disguised as a priest. His son James became James IV of Scotland, and he was struck with remorse for stirring up the trouble that had claimed the life of his father. The new king was said to have worn an iron chain around his waist each Lent thereafter as a penance for his role in the regicide. James III was buried in Cambuskenneth Abbey next to Queen Margaret who had died two years before.

James IV was only 15 when he took the throne, but he developed into a popular king with his interest in applying justice in every corner of his realm, the development of Scotland's first navy, and his promotion of such innovations as the printing press. Relations with England started brightly with his marriage to Margaret Tudor (1489-1541), daughter of Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509), but then deteriorated into warfare during the reign of Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547). James IV ruled Scotland until 1513 when he was killed in battle against the English and so was succeeded by his son, James V of Scotland (r. 1513-1542).