Helen is a Greek tragedy by Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE). It is usually thought to have first been performed at the Great Dionysia of 412 BCE and was part of the trilogy that included Euripides' lost Andromeda. Helen recounts an unusual version of the myth of Helen of Troy in which a phantom decoy, an eidolon, replaces Helen in Troy while the real Helen awaits the end of the Trojan War in Egypt. Ever since its first performance, Euripides' Helen has puzzled and fascinated: in his Thesmophoriazusae, performed the year after Euripides' Helen, Greek comedy playwright Aristophanes would parody the “new Helen” (line 850). To this day, scholars continue to debate many aspects of Euripides' Helen, including its jarring juxtaposition of the comic and the devastating, its contemporary relevance, and its message about the nature of truth and reality.

Euripides

Born around 484 BCE, Euripides was the youngest of the three Athenian tragedians regarded as “canonical” since antiquity (the other two are Aeschylus and Sophocles). Of the 90 or so plays he composed during his lifetime, 18 survive in full (one of the tragedies transmitted under his name, Rhesus, is almost universally regarded as spurious). There are thus more surviving plays by Euripides than by Aeschylus and Sophocles put together, demonstrating that after his death Euripides soon eclipsed his two predecessors in popularity.

Little enough is known about Euripides' life, and what little information we have is obscured by fable and fancy. He was born to a family of hereditary priests on the island of Salamis, near Athens. He was said to have married twice, though both marriages ended acrimoniously. From one of his marriages, he had three sons, one of whom became a tragedian too. Above all, Euripides was reputed to have been a recluse, famously living in a cave in Salamis (which became a shrine to him after his death). Eventually, he retired to the court of King Archelaus of Macedon, where he died in 406 BCE.

Euripides is best known to us through his plays. These were performed at various festivals, chiefly the Dionysia and Lenaia, at huge outdoor theaters. Most of Euripides' plays were performed at Athens for audiences of locals and tourists, though some of his works would have been produced elsewhere: in Macedon, where Euripides spent the last years of his life, or Sicily, where he was apparently very popular. Even during his own lifetime, Euripides was known as the most adventurous and avant-garde of the great tragedians. This did not always translate to success, however. Over a career that spanned half a century (Euripides produced his first trilogy around 455 BCE and continued to compose tragedies until his death) Euripides won the first prize just four times during his life (a fifth time posthumously). On the other hand, Aeschylus was said to have been victorious 13 times and Sophocles 18. Euripides' tragedies – full of desperation, novelty, and relentless questioning – were sometimes regarded as sensational and even impious. But Euripides' fame and popularity grew after his death while that of Aeschylus and Sophocles declined. Today there are those that think of Euripides as the greatest of the Athenian tragedians.

The Myth

The myth of Helen is arguably best known from the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, which are usually thought to date to the 8th or 7th century BCE. In the Iliad, we find Helen in Troy living with her lover Paris: she had come to the city after running away from her husband, the Spartan king Menelaus, and for ten years Menelaus and the Greeks have been fighting to get her back. In the Odyssey, the Trojan War has ended with the fall of Troy and Helen's return to Sparta with Menelaus.

Between Homer and Euripides, many authors retold episodes from Helen's myth. Helen's marriage and the Trojan War seems to have been described in the pseudo-Hesiodic Catalogue of Women (fragments 23a, 197-204 M-W), probably composed in the 7th or 6th centuries BCE. Sappho (c. 620-570 BCE), described in one of her poems how Helen abandoned her husband and her family when she sailed off with Paris (Sappho 16). Euripides himself, in his tragedy Trojan Women of 415 BCE, staged Helen's encounter with the bitter Menelaus in the aftermath of the fall of Troy.

But in Euripides' Helen, we are confronted with a version of the myth in which Helen never goes to Troy at all. According to this tragedy, Helen had been spirited away to Egypt while the gods gave Paris a phantom fashioned in her likeness. It was for the phantom that the Trojan War was fought. Meanwhile, Helen spends 17 years waiting in Egypt for Menelaus. At first, she comes under the protection of the Egyptian king Proteus, but after Proteus dies, she is forced to constantly dodge the advances of Proteus' son Theoclymenus, who demands that she marry him. When Menelaus arrives in Egypt after ten years of war and seven more of wandering, Helen is finally reunited with her husband. Though hounded by the dogged Theoclymenus, the two manage a daring escape with the help of Theoclymenus' sister Theonoe and return home together.

Though much of this strange story is Euripides' own, some elements occur in earlier authors. The Odyssey describes some of Menelaus and Helen's wanderings after the Trojan War as well as their detour in Egypt to consult the prophetic Proteus (4.351-592). It was probably a version of this Homeric story that Aeschylus used in his lost satyr play Proteus, performed together with the Oresteia trilogy of 468 BCE. But the myth that Helen never went to Troy and that the war was fought for a phantom seems to have originated with the 6th-century BCE poet Stesichorus. According to Plato (428/427 - 348/347 BCE), Stesichorus had written a poem called Helen which described Helen's adulterous affair with Paris. Shortly after composing this poem, Stesichorus went blind. Realizing that he had offended Helen, Stesichorus immediately composed a second poem – a Palinode (literally, “song reversed”) – in which he recanted the first and explained that Helen never sailed to Troy at all (Phaedrus 243a-b). Neither Stesichorus' Helen nor his Palinode survives, though Plato quotes a few key lines from the latter (Phaedrus 243a7-b1):

This story is not true: you did not board the well-benched ships, you did not come to the towers of Troy (my translation)

Apparently, in Stesichorus' Palinode Helen is guiltless, remaining loyal to her husband Menelaus while the war was fought for a phantom (see also Plato, Republic 586c). For correcting his mistake Stesichorus – so the story goes – promptly regained his vision.

Finally, around 450 BCE – a generation or so before Euripides' Helen premiered – the historian Herodotus (c. 484 - 425/417 BCE) published his Histories, in which gives his version of the Helen myth: Helen did elope with Paris, but when the two stopped in Egypt the virtuous king Proteus recognized their crime and detained Helen with him until she could be restored to her rightful husband. Meanwhile, the Greeks sailed to Troy to get Helen back. Not believing the Trojans when they told them that Helen was not there, the Greeks sacked the city only to find that the Trojans had been telling them the truth after all. Eventually, Menelaus' travels led him to Egypt where he found his wife and took her back to Sparta (113-19).

Euripides' Helen mixes and matches these different versions of the myth. But some details – Proteus' son Theoclymenus, for example – are almost certainly his invention. And, as always, how Euripides deploys his sources and what he does with the myth is entirely shaped by his inimitable genius.

Characters

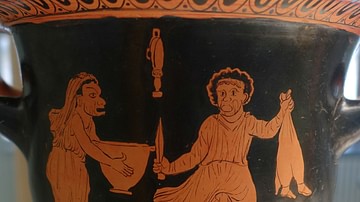

The play is set in Egypt before the palace. The altar in the middle of the orchestra (the stage) probably represented the tomb of Proteus.

The characters, in order of appearance, are:

- Helen (wife of Menelaus)

- Teucer (Greek warrior, from Salamis)

- Chorus of captive Spartan women

- Menelaus (king of Sparta)

- Old Woman (palace gatekeeper)

- Servant (of Menelaus)

- Theonoe (prophet, daughter of Proteus, sister of Theoclymenus)

- Theoclymenus (king of Egypt, son of Proteus, brother of Theonoe)

- Messenger (servant of Theoclymenus)

- Dioscuri (brothers of Helen)

Plot

Prologue: The play begins with Helen, standing before the tomb of the late king Proteus in Egypt. Helen introduces herself and provides the backstory: 17 years before, Paris had named Aphrodite as the most beautiful goddess in a contest (the Judgment of Paris) and in return was promised the hand of Helen in marriage; Paris sailed to Sparta, but the goddess Hera, angry at having lost to Aphrodite, fashioned a phantom in Helen's likeness to give to Paris; meanwhile, the real Helen was whisked away to Egypt by Hermes, where she was protected by king Proteus. For these last 17 years, Helen says, she has dutifully upheld her chastity, even after Proteus died and she was forced to fend off the marital pursuits of his son Theoclymenus. Though she knows that her name has been sullied by the phantom who has replaced her, Helen is determined to uphold her virtue and hopes to repair her reputation someday:

... even if my name is reviled in Greece, my body shall not here be put to shame. (66-67, tr. Kovacs)

As Helen comes to the end of her speech, the Greek warrior Teucer enters. Still under the impression that the phantom Helen was real, he is confused and angry to find another Helen in Egypt. Helen does not reveal her identity to him but questions him for news about the Greeks and the Trojan War. Teucer reveals that Helen's mother Leda has committed suicide, her brothers Castor and Polydeuces had disappeared, and her husband Menelaus is presumed dead. He also explains that he has been exiled from his homeland, Salamis, and is seeking advice from the prophet Theonoe. Helen warns him he should leave immediately as the new king Theoclymenus kills every Greek he comes across. Teucer exits.

Parodos: The Chorus enters. They and Helen lament that though Helen is innocent her name continues to be condemned among the Greeks.

Episode 1: In an interchange with the chorus, Helen considers her actions and vows to die if Menelaus is really dead. The chorus urges her to consult Theonoe first. All exit to do so.

Menelaus enters, dressed in rags. He boasts that he is the conqueror of Troy, and explains that after seven years of wandering he has been shipwrecked in Egypt. The phantom Helen – whom he still believes to be the real Helen – has been stowed away in a cave with the few of his men who have survived. The Old Woman detains him in a comic scene and informs him that Helen of Sparta is in Egypt. Menelaus leaves confused:

What am I to make of this? I hear of new troubles on the heels of old ones: I come bringing the wife I took from Troy, and she is being kept in a cave, and yet there's another woman, with the same name as my wife, living in this house. She said the woman was Zeus's daughter. Is there some man called Zeus by the banks of the Nile? No, there's only one, the one in heaven. And where on earth is there a Sparta except where the Eurotas flows past banks of lovely reeds? Tyndareus is the name of one man, not two. What other lands are called Lacedaemon and Troy? I do not know what to make of it. (483-99, tr. Kovacs)

Helen and the Chorus return, having consulted Theonoe and learning of Menelaus' imminent arrival in Egypt. Helen at first flees the ragged Menelaus but soon recognizes him and reveals herself. Menelaus, questioning the nature of reality, refuses to believe that she is the real Helen until his Servant reveals that the phantom in the cave had just exonerated Helen and vanished into thin air. Helen and Menelaus are reunited, and Menelaus notes that the Trojan War was fought for an illusion. But Menelaus does not have a ship, and the couple realizes they will be unable to leave Egypt without Theonoe's help: Theoclymenus still wants to marry Helen and will kill Menelaus if he finds out who he is.

Theonoe enters; Helen and Menelaus beseech her for her support. Theonoe promises not to reveal Menelaus' identity to her brother and to keep silent about their attempt to escape. After she leaves, Helen devises an escape plan: a mock sea funeral for the “dead” Menelaus.

Stasimon 1: The Chorus mourns those who died in the Trojan War. They question the nature of the gods and the reasons for war.

Episode 2: Theoclymenus enters. Helen introduces Menelaus but lies about his identity, introducing him as a shipwrecked Greek who saw her husband die at sea. Helen promises that she will marry Theoclymenus if he allows her to hold a sea funeral for Menelaus. Theoclymenus grants Helen's request.

Stasimon 2: The Chorus sings the myth of Demeter, who lost her daughter Persephone and went in search of her. They claim, strangely, that Helen had once offended Demeter.

Episode 3: Helen and Menelaus (now heroically clad in new armor) finish negotiating the preparations for the sea funeral with Theoclymenus. Helen explains that she must go with the others and that Menelaus must be in command of the ship. Theoclymenus concedes; Helen and Menelaus depart after Menelaus prays to Zeus for success in their venture.

Stasimon 3: The Chorus imagines Helen's glorious return to Sparta.

Episode 4: A Messenger rushes to the palace and tells Theoclymenus that Helen and Menelaus have deceived him; they have killed the Egyptian sailors, taken over the ship, and they are on their way to Sparta. Theoclymenus is furious and is on the verge of killing his sister Theonoe for not warning him of the treachery; the Chorus tries to prevent him. The Dioscuri appear as dei ex machina and reveal that all that happened was part of Zeus' plan. Helen will become a god like them, and Menelaus will go to the Isles of the Blessed when he dies. Theoclymenus agrees to accept this outcome.

Analysis

One of the most important themes of the play is the difference between reality and illusion. The premise of the tragedy is that the Trojan War was fought for a phantom Helen while the real Helen was in Egypt. Significantly, reality and illusion are in this instance indistinguishable: everybody thinks that the phantom Helen is the real Helen, including Helen's husband Menelaus (until, that is, the phantom vanishes). Helen often struggles with the conflict between her own innocence and the guilt implied by her name:

And for the fight against the Trojans I was put forward for the Greeks as a prize of war (though it was not me but only my name) (42-43, tr. Kovacs)

Euripides' Helen also reflects on the morality of and reasons for war. This was an important contemporary issue: when the tragedy was produced around 412 BCE, the Athenians and Spartans had been at war for nearly two decades (the Peloponnesian War). In 413 BC, the Athenians suffered a major setback after a large force they had sent to Syracuse as part of the Sicilian Expedition was wiped out virtually to the last man. Many Athenians watching Euripides' Helen would have sympathized with Menelaus, who remembers his men who died in war and at sea:

We can call the roll of those who perished and those who escaped sea perils and arrived home safely bearing the names of their dead comrades. (397-99, tr. Kovacs)

Also of interest is Menelaus' portrayal and Spartan nationality. Menelaus makes a fool of himself when he tries unsuccessfully to shove his way past the Old Woman to enter the palace, he is remarkably obtuse when it comes to grasping how the real Helen had been replaced with a phantom, and he would have been utterly helpless against Theoclymenus if not for Helen. This characterization seems to reflect an Athenian stereotype which construed Spartans as boorish, unintelligent bumpkins. Actually, Menelaus shows up in a handful of Euripides' plays (Andromache, Trojan Women, etc.), and he is portrayed as equally stupid in all of them. The cunning Helen, on the other hand, has been likened by some to the Athenian general and statesman Alcibiades. It is thus possible to read Euripides' Helen as a deeply topical work, reflecting the grim realities of Greek warfare in the late 5th century BCE.

Devastating as all this is, there are also moments of comic relief, such as the scene in which Menelaus is turned away from the palace by the Old Woman. The tragedy also has a “happy” ending, with Helen and Menelaus sailing away to Sparta together. This may seem surprising to many modern readers, and indeed, most of the best-known ancient tragedies (Aeschylus' Agamemnon, Sophocles' Oedipus the King and Antigone, Euripides' Medea) do not end on a happy note. But it is mistaken to believe that all Athenian tragedies were miserable, sad affairs. In fact, the idea that tragedy must be sad was one that developed gradually, through the influence of centuries of playwrights (such as Seneca and Shakespeare) and literary critics (such as Aristotle). In classical Greece, tragedies could be happy or even funny, and this did not make them any less tragic, and it certainly did not make them comedies or romances.