The Thesmophoriazusae (also called The Poet & the Women or Women at the Thesmophoria) is a two-act comedy play written in 411 BCE by the great Greek comic playwright, Aristophanes. The play's principal focus is on the Greek tragedian Euripides and his struggle with the women at the Thesmorphoria, a festival for women only held throughout Greece over a period of several days every fall. The festival honored the goddesses Demeter - sister of Zeus and goddess of agriculture - and her daughter Persephone. It promoted fertility both in the fields and at home. The celebration was held in the autumn for it was at this time of year when Persephone descended into the netherworld to be the wife of the god Hades. The play tells of the plight of Euripides as the women of Athens have grown tired of his portrayal of them in his plays and have finally plotted to kill him. Fearing for his life and curious as to the nature of his possible death, Euripides convinces his elderly relative Mnesilochus to go to the festival in the guise of a woman and speak on his behalf. As one might expect it does not go well for the old man and only the wit and wisdom of Euripides - using scenes from his own plays - saves his friend from possible misfortune.

Life of Aristophanes

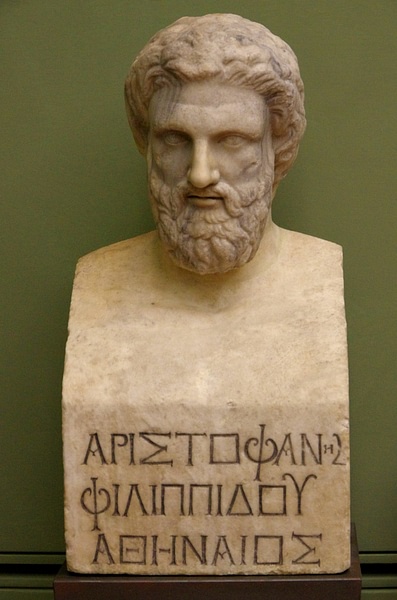

Very little is known of Aristophanes' early life - even his birthdate, possibly 447 or 445 BCE, is in question. Although his family owned land on the island of Aegina, Aristophanes, the son of Philippus and Zenodora, was a native of Athens. He had two sons of whom Aroses was a minor playwright. By the time Aristophanes began to write, Greek drama was in serious decline. Unfortunately, only eleven of his over 40 plays have survived. Editor Moses Hadas in his Greek Drama said Aristophanes could write delicate and refined poetry but could also demonstrate bawdiness and gaiety. His comedy was seen as a masterful blend of risqué wit and invention. Unfortunately, to many others, he brought Greek tragedy down from the high levels of Aeschylus with his use of parody, satire, and vulgarity. Aristophanes was an ardent opponent of the never-ending war between Athens and Sparta, and the pro-war advocate and statesman Cleon became an easy target for his ire. The playwright was even taken to court for his verbal attacks on Cleon in the play The Babylonians.

Although often criticized for their crude humor and suggestive tone, Aristophanes' plays were popular among the Athenian audiences. In her The Greek Way classicist Edith Hamilton said that all of Athenian life can be seen in his plays: the politics and politicians of the day, pacifism, fiscal reform, votes for women, and religious and literary talk. He wore the “halo of Greece.” According to historian Thomas R. Martin in his Ancient Greece, one significant characteristic of the playwright's comedies is how women used their wits and solidarity to compel the men of Athens to overthrow the basic politics of the city. Nowhere is this more evident than in Aristophanes' Women at the Thesmophoria.

A Summary of the Play

Euripides, the Greek tragedian, was troubled. He had learned that the women at the Thesmophoria festival had finally tired of his portrayal of them in his plays, and he feared they were plotting his death. He asked his fellow tragedian friend, the effeminate Agathon, to go to the festival in disguise and discover their plans. Agathon refused. Luckily, Euripides' good friend and relative Mnesilochus agreed to go. Borrowing the necessary clothes from Agathon, the newly-shorn Mnesilochus is sent to the festival. After sitting quietly listening to various women badmouth Euripides, he finally gets his opportunity to speak and defends the tragedian. He tells the women how their daily behavior is far worse than any of Euripides' plays have portrayed them. The women are livid. The Athenian Cleisthenes appears, informing them that a man, in disguise, may be spying on them. They quickly discover the disguised Mnesilochus. Trying to escape, he is captured, arrested by authorities and tied to a plank. After several failed attempts at rescue - using parodies from several of his own plays —Euripides finally appears, in person, and negotiates for Mnesilochus' release from the chorus women, promising to no longer insult them in any of his future plays.

Cast of Characters

- Euripedes

- Mnesilochus, a friend of Euripides

- Agathon, the tragedian

- Cleisthenes, a notorious homosexual

- a servant, a magistrate and a Scythian constable

- the Athenian woman Mica

- a second woman, Mica's friend Critylla,

- Echo (a character from one of Euripides' plays)

- the Chorus of Athenian women

- and the silent characters: Mania, Philista and Artemisia

The Play

Act One, Scene One finds the tragedian Euripides and his elderly relative Mnesilochus silently approaching the home of the playwright Agathon, an old friend of Euripides. Euripides tells the old man to be quiet and listen. The old man wonders where they are going, they take cover and soon see a servant exiting the home. Euripides appears from hiding and asks to see Agathon. “You must get him out here at all costs.” (79) Euripides is visibly upset - there is trouble brewing. Clearly, Mnesilochus does not know why they are there. Euripides tries to explain: “This day decides if Euripides lives or dies.” (80) At the festival of Thesmophoria, the women are going to decide his downfall, for in their eyes he denigrates them in his plays. He explains further, “I thought of persuading Agathon to go to the Thesmophoria …. He could sit in the assembly with all the women and, if necessary, speak in my defense” (80) Of course, Euripides adds, he would be in disguise.

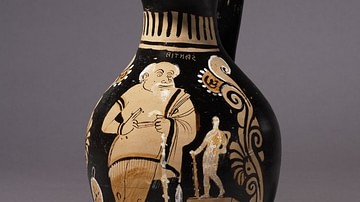

Dressed in a woman's attire and wearing a mask, Agathon appears from inside the house and after arguing with Mnesilochus - the old man says the poet has ants in his larynx - addresses Euripedes directly, “What do you have in mind? … What can I do for you?” (83). Euripides makes a plea to his fellow tragedian, he tells Agathon how the women at the festival are going to condemn him to death and pleas with Agathon to sit at the Thesmophoria and “speak up for me and save my life. No one but you can make a speech worthy of me.”(85). Agathon wonders why the tragedian doesn't go and speak on his own behalf. Euripides replies how he is too well-known and too old to go himself, but Agathon is “good-looking, fair-complexioned and clean shaven. You have a woman's voice and dainty manners - you-re pretty to look at.” (83). Despite the compliments, Agathon abruptly refuses. The hapless Euripedes exclaims that he is done for, but out of the blue, Mnesilochus volunteers to go to the festival in disguise. “…use me instead. I'll do anything.” (84). Unfortunately for him to become convincing as a women, he must be shaved clean and singed. Borrowing a dress and wig from Agathon, Euripides addresses his friend, “Well, you certainly look like a women now, Just make sure you put on a feminine voice when you speak.” (87).

Scene Two opens at the Temple of Demeter Thesmophoros. Women slowly enter. Mnesilochus mingles among the crowd. It is the second day of the festival and it has been proposed to punish Euripides - who has already been unanimously found guilty. The Athenian Mica speaks, “Is there any crime he has not accused us of? Wherever there is a stage and a theatre full of punters, there he is, coming out with his slanders, calling us double-dealers, strumpets, boozers, cheats, gossips, bad eggs, and a curse upon mankind.” (91). A second woman speaks and tells how her business was ruined because of Euripides. She sells myrtle chaplets in the market place, but after Euripides proclaimed there were no gods, she lost customers. “I tell you ladies one and all, that man ought to be punished for all he's done; he's so harsh to us.” (92).

Mnesilochus stood and began to speak, claiming he was also annoyed with Euripides. However, he asked the women why were they so mad at the tragedian. Could it be because he exposed all of their tricks? Speaking as a woman, he said they all, among other things, cheat on their husbands. “I ask you, ladies, do we do these things? Of course, we do. Why be so angry with Euripides? We suffer nothing worse than we deserve.” (94). The women become outraged and threaten to pluck and singe his (her) hair. Mnesilochus continued undeterred. “He never let on about the woman who killed her husband with an axe; or the one who gave her husband a drug that sent him mad…” (95). He added that there weren't any more women like Penelope.

As Mnesilochus speaks, the Athenian Cleisthenes, dressed like a woman and clean shaven, enters. Breathless, he informs the crowd that Euripides has sent an old man, a relative of his, to spy on them. He was to listen and discover their plans. Cleisthenes agrees to help them find the culprit. Mnesilochus plays innocent, “…what man would be stupid as to let himself be singed? (96). It was at this point, realizing he would soon be discovered, that Mnesilochus attempts to escape. Since he was the only one that no one else knew, he was questioned. Assuming he was the spy, they begin to strip him. His ruse had been uncovered. Cleisthenes immediately leaves to inform the city council.

In a sudden desperate move, Mnesilochus grabs what he believes to be a baby and threatens it unless he is allowed to leave, only to realize sadly that it was only a skein of wine. Mica and her nursemaid leave to gather kindling. They soon return. Using a trick from one of Euripides' own plays, Mnesilochus writes messages on votive tablets from the temple walls and scatters them. He then sits and waits for Euripides to come and save him.

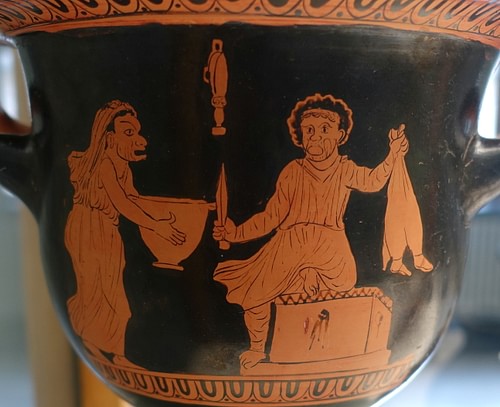

Act Two finds Mnesilochus nervously sitting at the altar guarded by Mica's friend Critylla who tells him to be silent. Oddly, Mnesilochus assumes the guise of Helen of Troy, wife of King Menelaus. Euripides arrives dressed as the Spartan king. “Unto what country have we steered our ship?” (109) “Egypt” the old man (as Helen) replies. A confused Critylla tells Euripides, "I tell you, sir, the man is up to no good.” (110). Mnesilochus (still in the guise of Helen) asks Euripides (Menelaus) to “take me in your arms.” However, Critylla does not fall for the trick, “Anyone who tries to take you out of here will feel the hot end of this torch.” (111). As a magistrate and a Scythian guard approach, Euripides departs. “Don't worry. I won't let you down, so long as I live and breathe. I've got hundreds of tricks left.” (111) Pointing to Mnesilochus, the magistrate asks, “Is this the culprit …Take him off and tie him to the plank. Then stand him up out here so you can keep your eye on him.” (111). Mnesilochus requests not to be left dressed as a woman - he doesn't want to give the crowd a laugh. The magistrate refuses. Having tied him to a plank, the Scythian props him up against one of the altar's columns.

Euripides then appears dressed as the Greek hero Perseus - another character from one of his plays. Just as he departs - he sees the guard returning - the feminine voice of Echo is heard. The unknowing Scythian guard begins a long talk with Echo but, of course, Echo can only repeat the last words that she heard. Confused, the guard tries to find Echo but fails. As her voice fades away, Euripides reappears, still dressed as Perseus, claiming to have the Gorgon's head. He tells the Scythian that Mnesilochus is actually Andromeda, child of Cepheus, and asks him to release her bonds so he can carry her away to the bridal bed. Undeterred, the Scythian does not release him. Realizing the guard was a “witless fool,” Euripides leaves. The Scythian falls asleep. Soon, Euripides returns and speaks to the chorus:

Ladies, if you would like to come to terms from now on, this is your chance. I promise solemnly never to say anything bad about you again. This is a serious offer. (120)

He pleads for the release of Mnesilochus. The plea is accepted. Euripides reemerges dressed as an old woman. To trick the Scythian and release Mnesilochus, a dancing girl emerges and begins to dance before the Scythian. She leaves with the guard in pursuit. Mnesilochus is immediately freed and runs off. The guard returns and sees his prisoner has escaped. He looks for the old woman. Realizing he had been tricked, he runs after the disguised Euripides.

Summary

Although written at the time of Athens' war with Sparta, the Thesmophoriazusae is seen as the least political of Aristophanes' plays. It was a time of upheaval and distrust and the climate in the city was not receptive to political satire, Like several of his others plays (Archarnians and Frogs), he uses his fellow playwright Euripides as one of his characters. Only in this play, though, is he seen as the principal character, A unique twist in the plays has Euripides using characters from the tragedian's own plays (Helen and Andromeda) in order to free Mnesilochus. According to the editors of Aristophanes: Frogs and Other Plays, Euripides is portrayed as a more sympathetic character. Initially a comic hero, by the end of the play he saves his relative from a terrible fate and makes peace with the women of Athens.