The Frogs is a comedy play by Aristophanes (c. 445 - c. 385 BCE), the most famous of the comic playwrights of ancient Greece. Named after the creatures who composed the play's chorus, it won first prize at the dramatic festival at Lenaea in 405 BCE and, proving to be successful, it would later be performed at the Dionysia festival in Athens.

The play represented the last of the playwright's works written during the turbulent era of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. Although he endured prosecution for his continued attacks on the politician Cleon, The Frogs brought Aristophanes public honors for its promotion of Athenian unity. The play tells the story of Dionysos, the patron deity of theater, who complains about the sad state of Athenian drama. In an attempt to save tragedy from a generation of poor writers, Dionysos, disguised as the god Hercules, and his slave Xanthias, descend into Hades to bring Euripides back from the dead - the tragedian had died the previous year. However, before Dionysos can leave Hades and return to Athens, he is persuaded to serve as a judge at Hades' court over a contest between Euripides and Aeschylus as to who was the greatest Athenian tragic poet.

Aristophanes

Aristophanes was one of the best examples of the “grace, charm, and scope” of Old Attic Comedy. Unfortunately, his works from this period are the only ones known to exist - only eleven of his plays have survived. Little is known of his early life with even his birthdate unclear. The son of Philippus, he was a native of Athens but owned property on the Greek island of Aegina. He had two sons - one of whom, Aroses, composed a few minor comedies. Classicist Edith Hamilton in her book The Greek Way said that Aristophanes wore the halo of Greece: “Aristophanes' Athens is for the most part inhabited by a most disreputable lot of people, as unplatonic as possible” (101). All of Athenian life could be seen in his plays: its politics, politicians, complaining taxpayers, fiscal reforms and the city's general disgust at the on-going war between Athens and Sparta. “All was food for his mockery” (ibid). Athens was a city of unrest. Residents were confined to the city as Spartan armies loomed nearby. People were outraged at their ineffective leadership in both city government and on the battlefield. All of this served as ammunition for Aristophanes' plays.

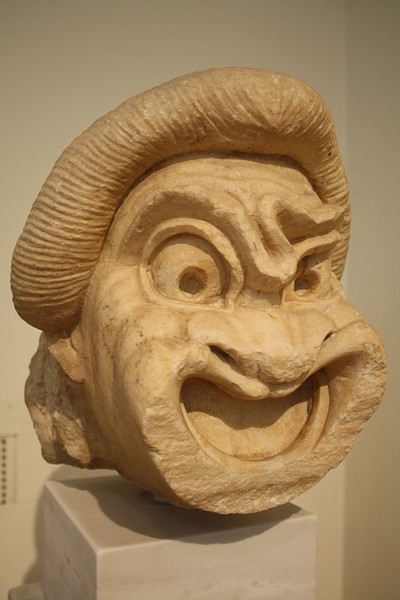

By the time Aristophanes began to write, Greek drama was in serious decline. Euripides was dead and Sophocles would die before the play was completed. However, as in tragedy, much of the presentation of a play remained the same: there were three or four actors (sometimes more) who wore grotesque masks and costumes as well as a chorus of 24 - even the chorus wore masks. Unlike tragedy, a comedy's purpose was to present beautifully written poetry while securing a laugh. Although Aristophanes is sometimes condemned for bringing tragedy down from the high level of Aeschylus, his plays, with their simplicity and vulgarity, were recognized and appreciated for their rich fantasy as well as bawdiness, gaiety, and satire. His comedy was a masterful blend of risqué wit and invention. According to Norman Cantor in his book Antiquity, his plays reflected the conservative opinions of the Athenian people who valued not only society's old simplicity but its morality, too.

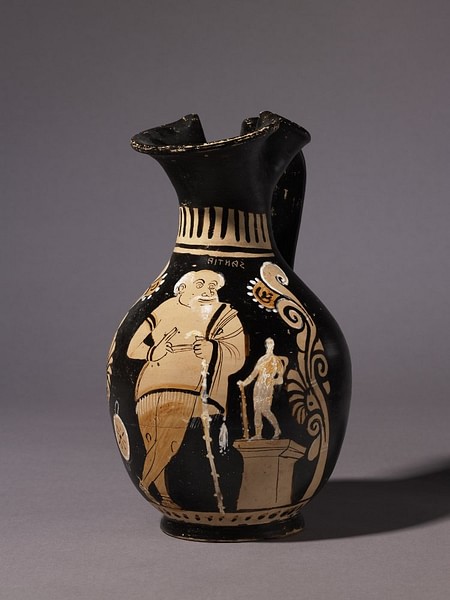

Aristophanes was an observer of Athenian society. David Barrett in his translation of Aristophanes said that the tension between the old and the new in Athens appears prominently in The Frogs and, like his predecessor Euripides, this change - the anti-war tension and political unrest - could be seen throughout his plays. Since his comedies often contained a theme of peace, many were led to believe he was a pacifist. Aristophanes' observations of his fellow Athenians and the city's poor leadership made him a staunch opponent of war. As a whole, his plays were used to ridicule politicians as well as philosophers: the statesman Cleon was a favorite recipient of his satire while Socrates was depicted as a traitor. Mythology and theology did not escape his scorn either - gods were often portrayed as both foolish and spineless.

Characters

The Frogs has a rather large cast of characters:

- Dionysos

- Xanthias

- Hercules

- Euripides

- Aeschylus

- Hades

- Charon (ferryman of the dead)

- Aeacus (doorkeeper of Hades)

- two landladies

- a maid

- a slave

- and two choruses - one of initiates and one of frogs.

Plot

Meeting Hercules

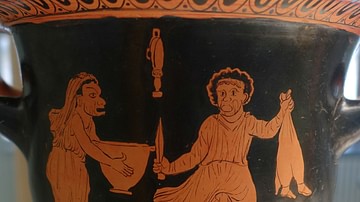

The play opens with Dionysos and his servant Xanthias arriving at Hercules' home. In a futile attempt to disguise himself as Hercules, Dionysos is dressed in a yellow robe covered by a lion-skin. Hercules opens the door and begins to laugh at Dionysus' attire.

Sorry, friend, I couldn't help it. A lion-skin over a yellow negligee! What's going on? Why the high-heel boots? Why the club? What's your regiment? (Barrett, 135)

They ask Hercules how he had made his way into Hades and explain they hoped to bring back Euripides from the dead. Dionysos explains, “I need a poet who can really write. Nowadays it seems like many are gone, and those that live are bad.” (136). Hercules responds by naming a number of capable, young poets (Iophon and Agathon) but Dionysos contends that none of them is genuine. “…insignificant squeakers, twittering like a choir of swallows. A disgrace to their calling.” (137). He adds, “I defy you to find a genuine poet among the whole lot of them, one who can coin a memorable line” (137). In order to restore Athenian tragedy, he must go to Hades and bring back Euripides. So, what's the best way to get to there? Trying to scare the deity, Hercules tells him of the possible terrors: snakes, wild beasts, the Great Mire of Filth and the Eternal Stream of Dung. His warnings, though, have little effect.

Traveling to Hades

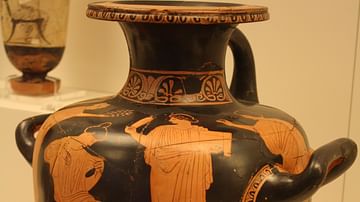

Dionysos leaves and arrives at a large lake where Charon, the ferryman, escorts him across to Hades. Xanthias arrives by another, longer route. While on the boat, Dionysos, who had to help row, continually complains about his “sore bottom” and his blisters. He gets into a heated argument with a chorus of frogs - singing frogs that refuse to be silenced: "Now listen, you lyrical twerps, I don't give a damn for your burps” (144).

As they move away from the lake, they are approached by a singing and dancing chorus of initiates, chanting hymns to Demeter, Persephone, and Iacchus. The two travelers decide to join the dance but finally interrupt to ask for and receive, directions to Hades' home. At the palace door of Hades, they (Dionysos still being disguised as Hercules) are greeted by Aeacus, the doorkeeper. Fearful, Dionysos exchanges clothes with Xanthias. After an altercation with a landlady over who exactly is who, the doorkeeper decides to let Hades and Persephone determine who is the god and who the servant.

Euripides v. Aeschylus

Later, Xanthias and a slave begin to talk. They overhear shouting coming from inside Hades' home. The slave tells him that there is trouble in Hades:

Well, there's a custom down here that applies to all the fine arts and skilled professions: whoever's the best in each discipline has the right to his dinner in the Great Hall with his own chair of honor? (164).

Xanthias learns that Aeschylus had the chair but now Euripides has challenged him for it. It seems he appealed to all the cut-throats and murderers for support. So, Hades decided to have a contest between Euripides and Aeschylus - Sophocles had renounced any claim. Scales are soon brought in: “…. It's all got to be measured properly, with rulers, yardsticks, compasses, and wedges, and god knows what else” (165). When Xanthias inquired about the judge of the contest, the slave said it would be difficult to find someone clever enough in Hades, and Aeschylus didn't see eye to eye with any Athenians.

The contest begins with Euripides' verbal assaults on Aeschylus:

I saw through him years ago, All that rugged grandeur —- it's all so uncultivated and unrestrained. No subtlety whatsoever. Just a torrent of verbiage… (166)

Aeschylus responds that his plays have lived on while Euripides' died with him. Throughout the contest, the two poets make references to their plays. Euripides says, “I wrote about everyday things, things the audience know about and could take up on if necessary. I didn't try to bludgeon them into submission with long words” (171). He believed he added logic to his drama. Aeschylus says that it pained him to have to answer verbal attacks but in frustration, he finally asks Euripedes what qualities does one look for in a good poet. The reply: to teach people to be better citizens. Aeschylus responded:

My heroes weren't like these marketplace loafers, delinquents and rogues they write about nowadays. They were real heroes, breathing spears and lances… (172)

Aeschylus the Winner

Finally, Aeschylus grows tired of the contest and asks for the test of the scales. Dionysos looks at both men:

I came down here for a poet. What for? To save a city, of course! Otherwise there won't be any more drama festivals - and then where would I be?...I'll judge between you on this score alone. I shall select the man my soul desires. (188)

In the end, Dionysos chooses Aeschylus. Of course, feeling betrayed, Euripides calls him a traitor: “You leave me here to stay deceased” (189). As they leave the palace Hades bids Aeschylus goodbye and advises him to “educate the fools” (189). Aeschylus walks away, telling Hades to keep that lying foul-mouthed rogue out of his chair.

Legacy

Aristophanes was the last of the great playwrights of Old Attic Comedy. His acerbic wit can even be seen in Plato's Symposium where he discusses the origin of the species of man. One unique aspect of The Frogs concerns the tragedian Sophocles who died during the writing of the play. Aristophanes was forced to make several quick changes. Like his contemporaries, Aristophanes used his plays to critique Athenian society: its political unrest and involvement in the war against Sparta. In his book The Classical Greeks, Michael Grant says that Aristophanes wrote The Frogs during a time when military and political power in the city was on the verge of collapse. In an attempt to escape the world he sends Dionysos to Hades. He adds that his plays contain assaults on Athenian political figures but also a plea for peace. Although often criticized for their bawdiness and risqué tone, Aristophanes plays were popular among the Athenian audiences. His plays remained appreciated and admired for years after his death, influenced Hellenistic and Roman comedy, and are still regularly performed today.