The German Peasants' War (1524-1525) was a conflict between the lower class of the Germanic region of the Holy Roman Empire and the nobility over the feudal system of serfdom, religious freedom, and economic disparity. It was later characterized as epitomizing the struggle between the working class and their overlords by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

The causes of the peasants' revolt are still debated, but, essentially, the rise of humanistic philosophy coupled with the religious reform movement of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) challenged the status quo and led the lower class to hope for a radical change in the social hierarchy. The Knight's Revolt (1522-1523) is also cited as a contributing factor in that the knights under the leadership of Franz von Sickingen (l. 1481-1523) and encouraged by the knight-poet Ulrich von Hutten (l. 1488-1523) refused to pay taxes or tithes and encouraged peasants to do the same. At this time, the Roman Catholic Church took 10% of the peasants' wages as a tithe, and the nobility claimed other percentages based on their own tax systems, forcing the peasant population to live in poverty.

After Luther challenged the authority of the Church in 1517-1521, igniting the Protestant Reformation, other members of the clergy followed suit, such as Thomas Müntzer (l. c. 1489-1525), who initially hoped Luther would advocate for peasants' rights and, when he did not, denounced him for betraying the cause. The nobleman and knight Florian Geyer (l. c. 1490-1525), another admirer of Luther, joined Müntzer, the peasant leader Hans Müller (d. 1525), nobleman Wendel Hipler (d. 1526), and others in organizing a revolt against what they saw as unchristian and inequitable policies of the Church and nobility.

The peasants were poorly armed as compared with the armies of the nobility, lacked experienced leadership, and failed to present a united front, leading to their defeat in 1525 after a number of engagements, which were often more massacres than battles. It is estimated that approximately 100,000 German peasants were killed in the conflict, with more dying from starvation after the destruction of farmlands.

In some respects, the struggle mirrored the earlier Hussite Wars (1419 to c.1434) in pitting a peasant class against professional armies of the nobility, but there was no strong leader such as Jan Žižka (l. c. 1360-1424) for the Germanic peasants who were no match for the superior tactics and weaponry of the nobility. Marx and Engels, the German philosophers who formulated the system of Marxism and co-wrote The Communist Manifesto in 1848, characterized the conflict as epitomizing class struggle and the peasant leaders as proto-Communist heroes.

Social & Religious Background

European society at this time was still operating according to the structure of the Middle Ages, with the nobility at the top of the hierarchy and the peasantry at the very bottom. In between there were lesser nobles, presiding over smaller fiefdoms, the clergy (some of whom were more powerful than the lesser nobles), and the merchant class, many of whom claimed tax-exempt status as the clergy did. The Church, recognized as the sole spiritual authority, required a 10% tithe from adherents in addition to other fees for various services. These four classes all relied on funds from the lowest class, who were continually taxed into poverty.

The peasant class had gained greater autonomy and financial security during the Middle Ages when the combination of the Crusades and the Black Death had killed off a large percentage of the population, allowing peasants to assert themselves and charge the lords more for their labor. Whatever they made, however, could not keep up with the taxes levied by the upper classes and the demand for more of their labor. When Martin Luther's 95 Theses were popularized between 1517 and 1519, many peasants interpreted them as a challenge to the status quo and supported Luther as a champion of the common people against the aristocracy and the Church, and a number of middle- and lower-class clergy supported Luther in the hope of a complete religious revolution that would end ecclesiastical corruption.

One of these clergymen was Thomas Müntzer, who began questioning the teachings and policies of the Church as early as 1514. By 1517, he was in Wittenberg when Luther posted his 95 Theses, traveled to Leipzig in 1519 to support Luther in his disputation with the Church, and seems to have still regarded himself as a follower of the reformer in 1521 when he arrived in Prague to preach. By this time, however, he had become increasingly interested in German mysticism and the validity of dreams and visions as messages from God.

Müntzer was also convinced that he was living in the last days and that Jesus Christ's return was imminent. In accordance with scripture, which he held on par with revelations in dreams and signs, he felt he needed to make ready for the Day of the Lord. At this point, he broke with Luther's teachings and began encouraging more radical reform. He was dismissed from his position in Prague and traveled to Allstedt, Saxony, where he continued to preach as he had before. By this time, Luther had become aware of Müntzer's radicalism and, fearing it jeopardized the Reform movement, ordered him to Wittenberg to explain himself, but Müntzer refused.

In the same way that reformer Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) in Switzerland had inspired the more radical movement of the Anabaptists, Luther's movement in Germany encouraged Müntzer's vision of complete social and religious reform. Luther held the scripture to be the final authority on religious matters which then informed society and denounced Müntzer's attack on the social order in accordance with biblical passages such as Ephesians 6:5-9, which begins with the line, "Servants, obey your earthly masters with respect and fear, and with sincerity of heart, just as you would obey Christ." Müntzer rejected this criticism as he believed the Bible was only one means by which God spoke to humanity.

Insurrection & The Twelve Articles

Müntzer's vision appealed to a broad segment of the peasant population, tired of heavy taxation and almost no rights of property and zero autonomy. Peasants were prohibited from fishing and hunting on lands they occupied because those lands technically belonged to their lords, and these lords were free to ride through their crops on hunts whenever they pleased. When a peasant head of the household died, his tools and anything else of value could be seized by the lord instead of passed down to the man's sons, and in addition to these affronts, there were the exorbitant taxes, greater demands on labor, and further restrictions on personal liberties.

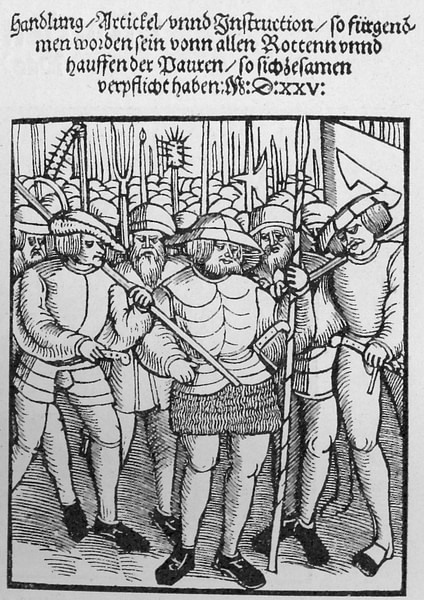

Although Müntzer cannot be credited as the sole inspiration for the German Peasants' War, his apocalyptic vision of a new order encouraged a real hope among the peasantry that the time was at hand to overthrow the nobility and assert their rights as free people capable of directing their own lives. By 1524, peasants had formed into territorial democratic groups (known as Haufen – bands) each with its own governing body (the Ring) which agreed on laws, maintained order, and directed the actions of the rest. These groups ranged in size from 2,000 to 8,000 and up, depending on the population of a given territory. In the late summer/fall of 1524, a group of peasants rebelled in the southern Germanic regions after a countess demanded they leave off their harvest work to collect snail shells for her to use as thread spools.

The insurrection spread quickly as peasant bands had already been formed and organized. These groups were able to set their complaints before the local magistrates in writing, and the major complaints were finally fully articulated in the Twelve Articles in March 1525. This was a document asserting peasants' rights and calling for the redress of wrongs submitted to the Swabian League (1488-1534), an alliance of the nobility who maintained the social structure.

Sebastian Lotzer (l. c. 1490 to c. 1525), a furrier who became secretary to a contingent of the peasants' army, is thought to have written the Twelve Articles with the Reformed theologian Christoph Schappeler (l. 1472-1551), though Wendel Hipler and Müntzer may also have contributed. The Articles addressed a number of points, including greater autonomy, tax relief, more equitable laws, and the abolishment of the inheritance tax. The Twelve Articles are regarded as the first document concerning human rights in Europe in the Early Modern Era, but they were rejected by the nobility, and that decision was supported by Martin Luther.

Luther & Müntzer

Luther owed his life to the nobility, specifically to the Elector Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525) who had taken him into protective custody after he had been condemned as a heretic and outlaw following his appearance at the Diet of Worms. Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms had broken his ties with the Church and established his Reformed vision, increasing his popularity among the peasant class, but he would have been prevented from continuing his efforts if not for the protection offered by Frederick III.

When the insurrection began, Luther came out of hiding to preach against it, citing biblical passages in support of maintaining social order. Müntzer felt he had betrayed his initial vision and the people and began writing a series of letters attacking Luther as "Doctor Liar" and condemning him as a pawn of the nobility. To Müntzer, the Lutheran nobles had no true religious conviction in supporting Luther's movement, they were only interested in what they could gain financially by breaking with the powerful Church, which owned many fertile tracts of land, paid no taxes, and required a tithe from them as from every other class, and he was right about this.

Luther condemned Müntzer as a dangerous radical who was inciting civil unrest and endangering the Reformation movement, but Müntzer rejected these accusations and appealed directly to the people, writing in his Vindication and Refutation of 1524:

Open your eyes! What is the evil brew from which all usury, theft, and robbery springs but the assumption of our lords and princes that all creatures are their property? The fish in the water, the birds in the air, the plants on the face of the earth – it all has to belong to them!...And Doctor Liar responds, Amen. It is the lords themselves who make the poor man their enemy. If they refuse to do away with the causes of insurrection, how can trouble be avoided in the long run? If saying that makes me an inciter to insurrection, so be it! (Janz, 165)

Müntzer's arguments struck a chord among the peasantry, naturally, but also among some of the lesser nobility who had lost lands, prestige, and revenue to the more powerful Lutheran princes. Among these was Florian Geyer who, like Müntzer, had been an early supporter of Luther, but by 1524, sided with the more radical Reformed vision Müntzer and his fellow revolutionaries advocated.

The German Peasants' War

The insurrections of 1524 grew more widespread until, by early 1525, the peasants were in complete revolt and had formed into armies, supported and encouraged by Anabaptist clergy who, though pacifists, saw the peasants' cause as just. There were a number of small conflicts between January and April of 1525 in which the peasants used tactics learned from the Hussite Wars, notably the wagon fort – a moveable fortification garrisoned by archers and pikemen – but the first full-scale engagement was the Battle of Leipheim on 4 April 1525 which pitted approximately 5,000 peasants against over 8,000 professionally trained troops of the Swabian League. The peasants were cut down in retreat, with losses estimated at over 3,000 killed.

The peasant army under Jakob Rohrbach retaliated by taking the village of Weinsberg, capturing the castle, slaughtering the soldiers, and forcing the nobles they captured to run a gauntlet of pikes and cudgels, beating them to death as they made their way down the line. Müntzer, meanwhile, was leading his own armies against the forces of the Swabian League with support from Geyer and his Black Company, a formation of knights who focused on the destruction of castles and monasteries that could serve as fortifications for the enemy.

Although each peasant army had the same goal, few worked in a concerted effort to support each other. The peasant leaders, as noted, made decisions in an assembly of no more than twelve men and then put their plans into action without consulting with other bands. Hans Müller seems to have operated without consulting Müntzer, and, while Geyer is said to have supported the troops under Müntzer, it is unclear what form this took and whether this was a concerted, organized effort or, perhaps, that Geyer gave support if he happened to be in the same area as Müntzer at a given time.

The peasant armies were opposed by a number of powerful nobles but chiefly, by Georg III, Truchsess von Waldburg ("Truchsess" meaning steward, l. 1488-1531), an experienced soldier and military commander who, after his victory at Leipheim, consistently won every engagement, torturing captives before executing them, and burning villages as he marched. On 12 May 1525, Georg III met a large peasant army at the Battle of Boblingen, broke their lines easily with his cavalry, and slaughtered them in retreat. The peasants lost at least 3,000 soldiers, while Georg III's casualties numbered less than 40.

The decisive battle of the war came only a few days later, 15 May 1525, when the Swabian League forces of Philip I of Hesse (l. 1504-1567), another supporter of Luther, and those of George, Duke of Saxony (l. 1471-1539), who opposed Luther's Reformation, met the peasant army under Müntzer near the town of Frankenhausen. Müntzer had recently executed three servants of the noble Count Ernst claiming 'divine justice' had demanded their deaths and now used the same justification to rally his troops to defend the town. Scholar Lyndal Roper writes:

According to the Mansfeld councilor Johan Ruhel, who wrote to Luther about what happened, Muntzer rode around the camp on the day of the battle on May 15, 1535, shouting that the peasants should trust in the power of God, that the very stones would give way to them, and the shots would not harm them. But the peasants had been surrounded and, mostly foot soldiers, they were no match for the cavalry of Hesse and Bruswick, and the troops of Duke George of Saxony. Perhaps as many as six thousand were slaughtered; six hundred were taken captive. Most of the population of Frankenhausen died or were taken prisoner. (254)

Müntzer fled the field and hid in the room of a house in the town. When he was discovered, he claimed to be a poor invalid who had nothing to do with the war, but a bag he carried contained a number of letters and documents identifying him. He was tortured over the next few days and then executed on 27 May 1525; the same fate befell Rohrbach for his command of the army at Weinsberg. Geyer, having heard that Frankenhausen was a peasant victory, rode to join Müntzer but was ambushed, and the Black Company was annihilated at the Battle of Ingolstadt.

Geyer may have fled the battle or may not have even been present; he was later assassinated by two servants who claimed to be escorting him to safety. The conflict continued throughout the summer of 1525, during which Hans Müller's forces were defeated and he was executed after torture. Wendel Hipler survived the war and died the following year. Hostilities finally concluded in September 1525 with over 100,000 peasant casualties and the restoration of the status quo.

Conclusion

Luther issued his famous condemnation of the peasant uprising, Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants in May 1525, encouraging the nobility to crush the uprising and anyone who favored peace and stability to help in that cause:

Therefore, let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish, than a rebel. It is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him, he will strike you, and a whole land with you. (Janz, 177)

Interestingly, this is the same stand the Church took against Luther himself, who had been condemned by the Edict of Worms as an outlaw rebel-priest in 1521, encouraging anyone who could to kill him, but was now recognized by Protestant princes, such as Philip I of Hesse, as a champion of Christian truth. Many of the peasants, and, as noted, their leaders, had expected Luther to support their cause and felt betrayed when he sided with the nobility. After the war, Luther lost the support of many peasants, and at one point was stoned by a peasant mob.

Müntzer and Geyer and the other leaders of the German Peasants' Revolt were cast as villains by both Catholic and Protestant writers until the 19th century when Marx and Engels presented them as proto-Communist revolutionaries striking a blow against Capitalist oppressors. The leaders of the German Peasants' War, especially Müntzer, are still understood this way in the history of some countries (certainly by Communist regimes past and present) and a segment of the scholarly community who recognize the revolt as a reasonable response to unreasonable demands placed on those who could least afford to meet them.