The German Crusade of 1197 CE, also known as the 'Emperor's Crusade', was led by the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI (r. 1191-1197 CE). Although the emperor died on his way east, his army did capture Beirut from the forces of the Ayyubid dynasty. Abandoning the siege of Toron when they heard of Henry's death in Sicily, the Crusaders left for home and, much like the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE), it was a case of what might have been if a Holy Roman Emperor had managed to conduct the campaign in person.

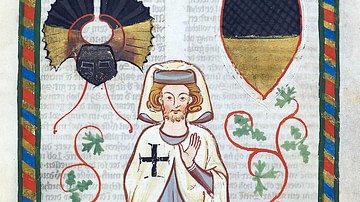

Henry VI

Henry VI Hohenstaufen had an excellent crusading pedigree as his father was Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1155-1190 CE) who had taken up the cross and amassed a huge army as part of the Third Crusade. Unfortunately, Frederick had died en route to the Holy Land somewhere in southern Cilicia. Most of the Germans then abandoned the Crusade which, despite still having the skills and armies of Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE) and Philip II of France (r. 1180-1223 CE), did not manage to take back Jerusalem from Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE). After Saladin's death in 1193 CE, the Ayyubid dynasty he founded continued to rule most of the Levant, but there were some serious squabbles over the succession and which of his heirs should rule what. Three sons each ruled Egypt, Damascus, and Aleppo and competed, ultimately unsuccessfully, with Saladin's brother Saif al-Adin for supremacy. It was a distracting rivalry that might help the Crusaders' ambitions in the region.

At Easter 1195 CE Henry VI 'took the cross' and vowed to crusade in the Holy Land in order to regain Christian control there. The emperor was, in reality, perhaps less bothered about the recapture of Jerusalem and much more concerned with taking on the Byzantine Empire. Henry VI's crusade was, in effect, a military manoeuvre calculated to extort from the Byzantine emperor Alexios III (r. 1195-1203 CE) a huge sum of cash to keep his throne. Alexios certainly saw the threat as real and imposed a tax in 1197 CE on his people, known bitterly as the Alamanikon or 'German' tax, in order to raise the necessary funds to pay off the Holy Roman Emperor.

Another development to help Henry with his eastern ambitions was the acquisition of Cyprus, given to him as part of the huge ransom paid for the release of Richard I, who had been held in captivity by Henry from 1192 to 1194 CE on a trumped-up charge of somehow being involved in the murder of Conrad of Montferrat. Conrad, the King of Jerusalem had mysteriously died a few days before his official coronation in April 1192 CE, and many pointed the finger at Richard, including the Holy Roman Emperor. Cyprus would prove to be a valuable staging point for many future crusades. Henry was already in control of Sicily - his wife Constance was the heiress - and so with a few more acquisitions in the Levant and the financial subjugation of the Byzantines, Henry may well have envisaged the creation of a Hohenstaufen empire stretching across the Mediterranean.

The Levant

In December 1195 CE, with the support of Pope Celestine III (r. 1191-1198 CE), Henry himself dished out crosses to new crusaders at Worms Cathedral. Gradually, as preachers toured Germany, England, and France for recruits, the emperor assembled an army for his crusade, although most warriors came from German lands. Important nobles who joined the adventure included Duke Henry of Brabant, Count Henry of the Rhine Palatinate, Duke Frederick of Austria, the Duke of Dalmatia and the Duke of Carinthia.

The departure date was set for Christmas 1196 CE. Setting off from the North Sea coast, the Crusaders stopped off in Portugal, as was not uncommon in the period. The fleet, carrying some 4,000 knights and 12,000 infantry, then assembled again at Bari in southern Italy in the summer of 1197 CE. On 22 September, the German force arrived at Acre in the Holy Land, and it was an opportune moment as the Crusader states, or Latin East as they were collectively sometimes known, were facing two crises.

The first crisis was the unexpected death, 12 days before the Germans arrived, of Henry II Count of Champagne, the king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (r. 1192-1197 CE). The king had bizarrely fallen from a window while reviewing troops at Acre, dragged out by a dwarf entertainer who himself had accidentally fallen (or vice-versa, depending on the version of the story). The king later died of his injuries - most of which were caused by the dwarf landing on him - and it left the Latin East temporarily without an overall leader. Henry II's widow Queen Isabella was technically still on the throne, but her children were not of age and all girls. Consequently, the Crusaders led on the spot by Henry VI's deputy Conrad of Mainz pushed for a remarriage of political and strategic convenience. Their choice was Aimery of Cyprus (aka Amalric), and the marriage would thus unify the two kingdoms of Cyprus and Jerusalem. It would also mean that as Henry VI had given Aimery his throne on Cyprus, the emperor would have his protege as the most important ruler the Latin East. So it was to be, and the wedding between Isabella and Aimery took place in January 1198 CE.

The second crisis was the end of the truce agreed with the Ayyubid dynasty. Al-Adin had already got the better of his nephew in Damascus and found time to repel an early group of the Crusaders who had raided Galilee. Al-Adin then moved to besiege Jaffa which fell after only a few days. The war between Christians and Muslims was on again.

Abandonment

The main army of the Crusaders did not waste any time and, after taking control of the now-ruined Sidon, they promptly began a successful siege of the important Muslim headquarters at Beirut, leaving Jaffa to its fate for the moment. The next siege target, on 28 November 1197 CE, was the city of Toron. This proved a more difficult nut to crack than Beirut, and the Crusaders were obliged to settle down for a real siege. It was then that the Crusade was dealt a crushing blow when news finally arrived from Sicily. On 28 September 1197 Henry VI, never enjoying a very robust physical health, had died of malaria in Messina. It was an extraordinary and tragic repetition of history, with both father and son emperors having died on Crusade before they had even reached the Holy Land.

Without their leader and concerned over what might now happen back in Europe and a contested succession - Henry's heir was his three-year-old son Frederick - the Crusaders abandoned their siege of Toron on 2 February 1198 CE. Most of the German army then sailed home. A deal was agreed between Aimery and al-Adil to hold a truce for 5 years and 8 months from July 1198 to 1204 CE. Under the terms of the agreement, the Christians would keep Beirut and the Muslims Jaffa.

Alexios III must have been hugely pleased to hear of Henry's death and find himself with a handy stockpile of cash he now need not hand over but keep for some other useful purpose. The Latin states were rather more disappointed at another lost opportunity to strengthen their hold of the coastal areas of Palestine and Syria, but at least there was hope of a new crusade. Another positive for the Christians was that the military order of Teutonic Knights had been officially established and recognised by the Pope. The order, like the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, would bolster the number of professional knights available for the defence of the Latin East. Indeed, the new pope, Innocent III (r. 1198-1216 CE) called for the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204 CE) but, diverted by Venetian commercial ambitions, that Crusade would end up attacking Constantinople and only a token and ineffectual force of western knights ever arrived in the Middle East.