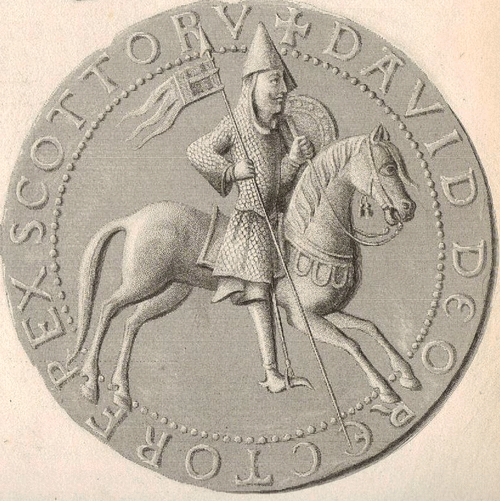

David I of Scotland reigned from 1124 to 1153 CE. Taking over from his elder brother Alexander I of Scotland (r. 1107-1124 CE), David continued to consolidate the kingdom of Scotland as a single nation, built castles and monasteries, and created new royal mints. The king was a wily military leader, and he took advantage of the civil wars south of the border following the death of Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE) to repeatedly attack northern England. Consequently, David forged a Scottish kingdom larger than that governed by any of his predecessors. He was succeeded by his young grandson Malcolm IV of Scotland (r. 1153-1165 CE).

Early Life

David was born c. 1084 CE, a member of the House of Canmore. His father was Malcolm III of Scotland (r. 1058-1093 CE) and his English mother was Queen Margaret (c. 1046-1093 CE), later to become better known as Saint Margaret of Scotland. Malcolm III had married his second wife Margaret, a Saxon princess, in 1070 CE after she had sought refuge in Scotland from the Norman Conquest of England. Margaret brought certain aspects of English culture to the Scottish court and promoted Roman Catholicism over the Gaelic Christianity that had previously been prevalent. When both Malcolm and Margaret died in 1093 CE, there was a reaction against this Anglicisation, and the royal princes and princesses, including David, were obliged to leave Scotland and find safety in northern England. Meanwhile, Malcolm III's brother Donald became king as Donald III of Scotland (r. 1093-1097 CE).

In 1097 CE Donald III was succeeded by Malcolm's elder brothers, first Edgar (r. 1097-1107 CE) and then Alexander I until 1124 CE. On his deathbed, Edgar had insisted that Alexander allow David to govern the lowlands of Scotland (Lothian, Teviotdale, and southern Strathclyde). David awarded himself the title 'Prince of the Cumbrian region'. From 1113 CE David had resided in the court of Henry I of England who had married David's sister Edith (renamed Matilda) in 1100 CE. David's star rose further when the king arranged for him to marry the widowed Countess Maud de Senlis in 1114 CE and so he acquired the immensely rich earldom of Huntingdon with its large estates in Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire. Maud was also something of a prestige catch, too, as she was a great-niece of William the Conqueror. The couple would have a son, Henry (b. c. 1115 CE), who became the Earl of Northumberland but who died of natural causes in 1152 CE, one year before his father. In the 1120s CE David participated in medieval tournaments in northern France and was now a thoroughly European noble in outlook and habits. When Alexander died in 1124 CE without a legitimate heir, David was declared king on 25 April, the first Scottish king to bear that name.

Rivalry with the Rebel Malcolm

Alexander had an illegitimate son, Malcolm, and he did have some support, notably in the more strongly Gaelic parts of Scotland. Malcolm's claim for the throne was strengthened when he married the sister of Somerled, the lord of Argyll. Malcolm gathered an army in 1125 CE, but it was defeated by David's supporters. Malcolm launched another rebellion in 1130 CE, this time with the support of Angus, the ruler of the Moray region and a descendant of Macbeth, King of Scotland (r. 1040-1057 CE). It was well-timed because the king was not in Scotland at the time. Once again, though, David crushed his challenger on the battlefield when his army was ably led by his constable, Edward fitz Siward. Angus was killed, and four years later Malcolm was imprisoned in Roxburgh Castle. David's throne was secure.

Governing Policies

David invited many English, Norman, and Flemish nobles to reside in the southern part of his kingdom where they gave military service in exchange for large estates or resided in David's newly created royal burghs where special privileges were given to encourage growth in trade (especially in wool and hides). Amongst the names that arrived were some which would become an important part of Scotland's future: the Comyns, Bruces, and Stewarts. In addition, the order of the Knights Templar was given a base at Balantrodoch, Midlothian, while the Knights Hospitaller received Torphichen, West Lothian. This hospitality to foreigners backfired tragically when a mad Norwegian monk killed David's infant son Malcolm.

Even before he became king, David had invited monks from Tiron near Chartres in France to found a monastery at Selkirk c. 1113 CE. Then during his reign, ten great Cistercian and Augustinian monasteries were founded, including those at Holyrood (c. 1128 CE), Melrose (1136 CE), and Jedburgh (1138 CE). Dunfermline Abbey was founded c. 1150 CE. The great castles of Edinburgh, Roxburgh, and Stirling were all rebuilt or made much grander. Indeed a whole line of castles was built between Aberdeen and Inverness to make sure the rebellious north of Scotland toed the line following David's campaign of subjugation there in 1130 CE. Another tool to impose the royal will - although one not yet universally applied across Scotland - was the many sheriffdoms created, each sheriff being typically headquartered at a royal castle and made responsible for collecting taxes (and later, administering justice).

The king did not always use force or officials to get his way, and David used diplomacy with great skill to get traditional leaders onto his side, such as the earls of Fife and clan leaders in the far north in Sutherland and Caithness. Finally, David centralised the government, formed an office to produce and keep written records, and created several royal mints, which hammered out silver pennies using metal from the rich mines near Carlisle. All of these policies helped David achieve an unprecedented level of control of Scotland and gave him a platform from which he could spring into military action south of the border.

Ambitions in England

Scotland had recently enjoyed a peaceful relationship with England, and the two royal houses had been tied when David's sister Edith married Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE) and his elder brother Alexander I of Scotland had married a daughter of the English king. However, when Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE) died in 1135 CE, he left no male heir, and his nominated successor, his daughter Empress Matilda (b. 1102 CE), was not to the liking of many powerful barons who preferred Stephen, the wealthiest man in England, grandson of William the Conqueror and nephew of Henry I. David even went so far as to declare Matilda - who was his niece - the Queen of England (a promise he had made Henry I), even if Stephen was married to Matilda of Boulogne (b. c. 1103 CE), another niece of David's. It was Stephen who was crowned king as Stephen of England (r. 1135-1154 CE), but the issue was far from being settled, and a period of on-off civil war followed that historians often call 'The Anarchy'.

David took full advantage of lax English control in the north of the kingdom. He invaded his neighbour, capturing the great castles of Carlisle and Newcastle, and laying siege to mighty Durham Castle, all essential for either kingdom to control the surrounding regions. However, King Stephen led a large army to the north in February 1136 CE, and David decided to settle for the old border arrangement for the time being. Under the terms of the Treaty of Durham, David gave up Newcastle but kept control of part of northwest England, including Carlisle Castle. At the same time, David's son Henry kept the title he had once held himself, the Earl of Huntingdon. As it turned out, both sides were not content with the agreement for very long.

In 1138 CE David sent an army to ravage northern England for a second time and so the Scottish king took over the counties of Westmorland, Cumberland, and Northumberland. David grabbed more key castles as his armies plundered the countryside and rounded up women to take as slaves. Even though Stephen enjoyed a victory near Northallerton in Yorkshire at the battle of the Standard on 22 August 1138 CE, by the 1140s CE David had effective control of northern England as far as the River Tees.

In May 1149 CE David knighted Henry Plantagenet, son of Empress Matilda and future Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE), at Carlisle, and Henry promised to maintain the status quo with Scotland, should he become king of England. Henry was the arch-enemy of King Stephen, and he joined forces with David to attack England once again. In 1149 CE, David even attempted to annex York into his kingdom, but this failure marked the turning of the tide; from then on, the English Crown would push the border back northwards.

Death & Successor

David spent his latter years gardening at Edinburgh Castle or in Carlisle, by then his main seat of government. The old king died on 24 May 1153 CE, and he was buried at Dunfermline in the abbey he had founded. David, without any living son (although there were two daughters, Claricia and Hodierna) was succeeded, as he had wished, by his 12-year-old grandson Malcolm (son of the late Henry, Earl of Northumberland) who became Malcolm IV of Scotland. Unfortunately for Scotland, Malcolm was no match for the new king south of the border, Henry II of England, and he gave up all the territorial gains David had made. Malcolm's troublesome 12-year reign was ended in 1165 CE when he died prematurely and still childless. The next king was Malcolm's brother, the colourful William I of Scotland (r. 1165-1214 CE) who became known as the 'William the Lion'. Thus, the House of Canmore would continue to rule Scotland until the death of Alexander III of Scotland (r. 1249-1286 CE).