Olives and olive oil were not only an important component of the ancient Mediterranean diet but also one of the most successful industries in antiquity. Cultivation of the olive spread with Phoenician and Greek colonization from Asia Minor to Iberia and North Africa and fine olive oil became a great trading commodity right through to the Roman period and beyond. The olive also came to have a wider cultural significance, most famously as a branch of peace and as the victor's crown in the ancient Olympic Games.

Geographical Spread

The olive was first cultivated around 5000 BCE, or even earlier, on the Carmel coast of ancient Israel. Here simple olive presses have been excavated at the Neolithic site of Kfar Samir. The success of the industry is attested by records of olive oil exports to Greece and Egypt throughout the 3rd millennium BCE. Greece started to produce its own olives on Minoan Crete and Cyprus in the Late Bronze Age and, thereafter, on the mainland. The Greeks, like the peoples of the Levant, were soon producing a surplus of olives and olive oil so that they built up a lucrative export industry. Such was its importance that it was the only permissible export in the celebrated laws created by Solon (c. 640 – c. 560 BCE). With the process of Phoenician and Greek colonization olive trees (Olea europea) sprang up across the ancient Mediterranean where all that was needed was warm summers and relatively light rainfall for these hardy trees to thrive.

Trees were spread to new areas by planting cuttings and ovules (trunk growths), or grafting domesticated trees onto wild ones. The Romans planted their cuttings in dedicated nursery beds to help them on their way. Long-lived and drought-resistant, the tree was a handily low-maintenance form of farming. Olive growers usually planted their trees in amongst fruit trees and reared animals so as to have some income in case of an olive crop failure, and it was an easy way to keep groves grass and weed free. The residue from pressing oil from olives could also be used as feed, especially for pigs.

From the 1st to 3rd centuries CE the Romans spread olive cultivation to more marginal growing areas such as central Tunisia and western Libya, which required extensive irrigation systems to make the farming viable. The Romans' dependency on olive oil is illustrated by Septimius Severus' decision to collect it as part of the taxes imposed on provinces and then redistribute it to the populace of Rome. As the Roman Empire expanded, so too did demand for olive oil, with Constantinople becoming one of the biggest importers. Indeed, the establishment of a huge number of olive farms (and vineyards) across Syria and Cilicia to meet this demand are credited with creating a regional economic boom in the 3rd-5th centuries CE.

The largest olive producers in the ancient world then were Greece, Italy, the Levant, the north coast of Africa, Spain, and Syria. Places which enjoyed a particularly high reputation in antiquity for fine quality oil included Attica, Baetica (in Spain), Cyrenaica (Libya), Samos, and Venafrum (Italy).

Production

Table-olives (made edible by salting) were eaten, but most of the crops produced went into making oil. Although oil was a common product, it was not necessarily a cheap one and, as with wine, there were different grades of quality. Olive trees produce a full harvest only every other year, sometime from October to December, and the Greeks believed that the earlier they were harvested (when still green) and pressed, the finer the oil. However, leaving collection later in the season allows for the olives to continue growing, ripen so that they become black, and so more oil can be pressed from them. The finest quality oil, as today, came from the first pressing and when the mash had the minimum number of stones in it.

Olives were crushed either underfoot (the crusher wearing wooden sandals), with pestle and mortar, using a stone roller, or in presses, the first mechanical ones coming from Klazomenai in Turkey. Dating to the 6th century BCE, these used a beam anchored to a wall and a stone weight to increase the pressure and efficiency of the press. The earliest known presses in Greece come from Olynthos. Several examples have been excavated which used circular millstones to crush the olives. One of the best-preserved olive presses comes from Hellenistic Argilos in northern Greece. As the machine evolved, a winch was added to bring down the beam with greater force.

As with most areas of everyday life, the Romans went one step further and made oil on a much larger scale. Large estates are described in detail by such authors as Cato. The Roman writer describes in his De agricultura the annual yield of one producer as between 50,000 and 100,000 litres of oil. The Romans first used a circular stone press (trapetum) which consisted of a large stone bowl (mortarium) into which the olives were poured and then crushed under two concave stones (orbes) attached to a central beam (cupa) fixed to an iron pivot (columella). This apparatus then slotted onto a central post (miliarium) set into the bowl which allowed the stones to be turned inside it. These rotary stone mills often harnessed animal power using mules to further increase efficiency. The Romans also moved on from the traditional beam and winch press to screw presses which dramatically increased the crushing pressure. This helped meet the ever-growing demand for olive oil as the empire expanded and resulted in production quantities not seen again until the 19th century CE.

Once pressed, the oil was drained off into a large stone settling tank set in the floor of the press room. Here the liquid mix of water, olive juice, and oil would settle and the oil rose to the surface where it could be skimmed off using a ladle or, alternatively, a tap in the base of the tank could be opened to drain away the water. When ready the finished oil was then stored in terracotta containers. At a pressing workshop on Delos six large pithoi vases held up to 4,000 litres of oil. There are records that oil produced in North Africa was shipped to Rome in oilskins. The most common storage vessel, though, was the amphora. These were very often stamped with such information as the producer's mark, place of manufacture, or production date, and then, if not used locally, were shipped across the Mediterranean.

Uses

Not only were olives and olive oil an important part of the Mediterranean diet and cooking process (and still are, of course) but the oil produced from pressed olives was also used for many other purposes. Greeks and Romans used it to clean their bodies after exercise – smearing it on so that it collected dirt and sweat and then scraping it off using a metal instrument called a strigil. Olive oil was used as a fuel in terracotta (and more rarely metal) lamps, as an ingredient of perfumes, in religious rituals, for massages, as a multi-purpose lubricant, and even prescribed as a medicine.

Impact on Culture

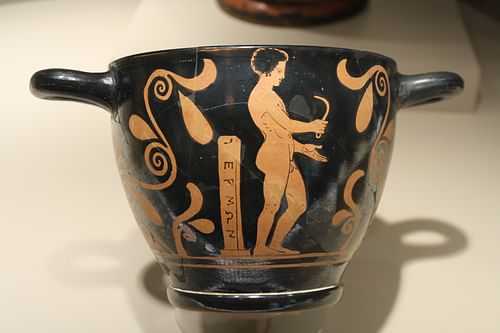

The importance of the olive to Greek culture is seen in the appearance of the olive branch on Classical Athenian coins and its use in the crowns of victory at the Olympic Games. The Athenians considered the olive tree a gift from their patron goddess Athena, and this very tree grew on the acropolis of the city. They had an entire sacred grove of olive trees (moriae) too, from which oil was pressed and placed into uniquely decorated amphora vases to be given as prizes in the annual Panathenaic festival.

Olive branches came to signify peace. Herodotus tells us that in the early 5th century BCE Aristagoras of Miletus carried one when he went to negotiate help from Cleomenes during the Ionian Revolt against Persia so that he would not be turned away from the Spartan king. Olive branches were also carried by pilgrims who visited the sacred oracle of Apollo at Delphi. The Romans continued this association and often depicted the god Mars, in his lesser-known guise as the bringer of peace, carrying an olive branch.