Female gladiators in ancient Rome – referred to by modern-day scholars as gladiatrix – may have been uncommon but they did exist. Evidence suggests that a number of women participated in the public games of Rome even though this practice was often criticized by Roman writers and attempts were made to regulate it through legislation.

Female gladiators are often referred to in ancient texts as ludia (female performers in a ludi, a festival or entertainment) or as mulieres (women) but not often as feminae (ladies) suggesting to some scholars that only lower-class women were drawn to the arena. There is a significant amount of evidence, however, that high-born women were as well. The term gladiatrix was never used in ancient times; it is a modern word first applied to female gladiators in the 1800's.

Women who chose a life in the arena – and it does seem this was a choice – may have been motivated by a desire for independence, a chance at fame, and financial rewards including remission of debt. Although it seems a woman gave up any claim to respectability as soon as she entered the arena, there is some evidence to suggest that female gladiators were honored as highly as their male counterparts.

Role of Women in Rome

Women in Rome – whether during time of the Republic or the later Empire – had few freedoms and were defined by their relationship to men. Scholar Brian K. Harvey writes:

Unlike men's virtues, women were praised for their home and married life. Their virtues included sexual fidelity (castitas), a sense of decency (pudicitia), love for her husband (caritas), marital concord (concordia), devotion to family (pietas), fertility (fecunditas), beauty (pulchritude), cheerfulness (hilaritas), and happiness (laetitia)…As exemplified by the power of the paterfamilias [husband or father, head of the house], Rome was a patriarchal society. (59)

Whether upper or lower class, women were expected to adhere to traditional expectations of behavior. Women's status is made clear through the many works by male writers which deal with the subject in depth and well as various legislative decrees. It is not known how women felt about their position since almost all the extant literature from Rome is written by men. Harvey notes that “we have almost no literary source that reveals a woman's perspective on her own life or the role of women in general” (59).

The one exception to this is the poetry of Sulpicia (l. 1st century BCE). In her first poem, celebrating falling in love, she says how she does not want to hide her love in “sealed documents” but will express it in verse and writes, “It is nice to go against the grain, as it is tiresome for a woman to constantly force her appearance to fit her reputation” (Harvey, 77). This reputation, of course, was forced upon a woman by males; first her father and then her husband.

Sulpicia was the daughter of Servius Sulpicius Rufus (l. c. 106-43 BCE), an author, orator, and jurist who was famous for his eloquence. As a writer himself, his daughter's literary pursuits were most likely encouraged but this was hardly the case for most women. Even in her case, she was still under the control of her father and her uncle Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (l. c. 64 BCE-8 CE). In her second poem, Sulpicia complains about Messalla's control over her in making birthday plans, writing that her uncle does “not allow me to live at my own discretion” (Harvey, 77).

Messalla Corvinus, like his brother, was also an author and an important patron of the arts. Sulpicia, then, was most likely brought up in an enlightened home where women could pursue literary endeavors and, based on her other poems, she also seems to have had the freedom to pursue a love affair with a man she calls Cerinthus who did not meet with the approval of her family. Even in this “liberated” environment, however, she still felt constrained and so it may be assumed a woman had far less freedom of choice in other more conservative homes.

Legislation Concerning Female Gladiators

It is due to the well-established patriarchy of Rome and women's place in it that scholars have had such difficulty accepting the concept of female gladiators. References to ludia are often interpreted to mean actresses in a religious festival – and this is an accurate interpretation – but the context of the term in some inscriptions makes clear that some women chose their own path as female gladiators and it seems this option was open to them over a considerable length of time.

In 11 CE the Roman Senate passed a law forbidding freeborn women under the age of 20 from participating in the games of the arena. This suggests the practice had been ongoing for some time previously. It should be noted that the decree specifies “freeborn females”, not female slaves, who are assumed to have still been able to participate. Emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) outlawed participation of any woman in the arena in 200 CE, claiming that such spectacles encouraged a lack of respect for women in general.

He was also motivated by the concern that women, if allowed to train as athletes, would want to participate in the Olympic Games in Greece; a prospect he found distasteful and threatening to the social order. Interestingly, his decree seems to have been motivated by the participation of high-born free women in the games – those who would have had all their material needs provided – who may have preferred the life of a gladiator to having their choices limited by male relatives.

In spite of the Severan decree, women were still fighting in the arena later in the 3rd century CE as evidenced by an inscription from Ostia, the port city near Rome. This inscription notes that the magistrate of the city, one Hostilianus, was the first to allow women to fight in the arena since Ostia's founding.

The wording of the inscription specifies that Hostilianus allowed mulieres to fight, not feminae and so it may be that Hostilianus was able to get around Severus' law by some legal loophole whereby free born ladies of the upper class were still prohibited but lower-class women and female slaves could still participate in the games.

Gladiators & the Games

The gladiatorial games began as an aspect of funeral services. Following the interment and funerary rituals, paid fighters would engage in games where they would enact scenes from popular literature and legend – or from the life of the deceased – as a tribute. Harvey notes that “the term for these games was munus (plural munera), which connoted a duty or obligation as well as a gift” (309). These games became increasingly popular entertainment with the people and eventually lost their association with funeral rites. Aristocrats – especially those running for office – would sponsor games to win support and these events eventually grew to include official celebrations of an emperor's birthday, coronation, or other state events.

The first gladiatorial games were held in 264 BCE by the sons of the senator Brutus Pera to honor their father after his funeral. They would continue for the next few centuries until finally outlawed under Honorius in 404 CE. During this time, thousands of people and animals would die in the arena for the entertainment of the people.

Contrary to popular opinion and depictions in film, gladiators were not sent into the arena to die and most contests did not end in death. Convicted criminals (damnati) were executed in the arena but most of those who fought there were slaves who had been highly trained and were quite valuable to their owners.

The Roman writer Seneca (l. 4 BCE-65 CE) describes a noon show at the arena which took place during the intermission between the morning and evening spectacles. This would have been the time of day when criminals were executed. These would include those convicted of serious crimes, deserters from the army, and those who incited sedition or were guilty of blasphemy or various other crimes against the state. Christians would eventually be included in the noon intermission spectacles:

These noon fighters are sent out with no armor of any kind; they are exposed to blows at all points, and no one ever strikes in vain...The crowd demands that the victor who has slain his opponent shall face the man who will slay him in turn; and the last conqueror is reserved for another butchering. The outcome for the combatants is death; the fight is waged with sword and fire. (Moral Epistles VII.3-5)

Seneca's description has become ingrained in the popular imagination as the paradigm of the games in the arena. Actual gladiatorial games (Ludum gladiatorium) were significantly different and the outcome was not always death. The opponents were evenly matched and would fight until one of them dropped shield and weapon, lifting a finger to signal surrender. The individual who sponsored the games (known as the munerarius) would then pause the fight. At this point, the famous pollice verso (“with thumb turned”) was given.

It is unclear whether the “thumbs down” meant death and it has been suggested the gesture was the munerarius' thumb drawn across his throat. The munerarius would consider the opinion of the crown before rendering a decision and could easily grant missio (allowing the gladiator to live) and call the contest with a decision of stans missus (“sent away standing”) which meant a draw. More gladiators were spared at this moment than killed because, if the munerarius chose death, he would have to compensate the lanista (owner of the gladiator) for the loss.

Gladiators certainly could be killed in their first fight in the arena but there are memorials and inscriptions which show that many fought and lived for years. It has been suggested, in fact, that female gladiators were often the daughters of retired gladiators who trained them. Gladiatorial schools abounded in Rome since their founding in c. 105 BCE and more schools proliferated in the colonies and provinces as the empire expanded.

Upon entering a Gladiatorial school, the novice took a vow to allow himself (or herself) to be whipped, burned and killed with steel and gave up all rights to his - or her - own life. The gladiator became the property of the master of the school who regulated everything in that person's life, from diet to daily exercise and, of course, trained the person to fight.

At the same time, it does not seem that women trained with men in the schools and there is no record of a woman fighting a man in any of the shows. Female gladiators were most likely trained by their fathers or in private lessons with a lanista. Wooden swords were used in training by both men and women following the revolt of the gladiator Spartacus (73-71 BCE) who had used the iron weapons of his school to launch the insurrection. Men and women were trained in different types of combat and there were four types of gladiator:

- The Myrmillo (Murmillo) had a helmet (with a fish crest), oblong shield and sword.

- The Retiarius (who usually fought a Myrmillo): lightly armed with a net and trident or dagger.

- The Samnite had a sword, visored helmet, and oblong shield.

- The Thracian (Thrax): armed with a curved blade (a sica) and round shield.

Each gladiator was taught to fight in one of these four disciplines and the reward for excellence in combat could be fame, fortune, and a lifestyle which "respectable" women in Rome could never dream of. In a later passage from the Moral Epistles cited above, Seneca complains that the people always needed to have some form of entertainment going on at the arena besides the standard shows and this need may have initially been met by female entertainers fighting dwarves (Adkins & Adkins, 348). In time, however, women left off participating in these kinds of shows to become gladiators.

Physical Evidence for Female Gladiators

Discovered in 1996 and announced in September 2000, the Remains of Great Dover Street Woman (also referred to as “Gladiator Girl”) provided physical evidence to back up the substantial literary evidence from antiquity that women fought as gladiators in the arena. The woman's pelvis was all that remained of the body after cremation but the abundance of expensive oil lamps, together with other evidence of a large and luxurious feast and the presence of pine cones (burned at the arena to purify it after the games) all contribute to the conclusion that this was the grave of a respected gladiator who was a woman.

Aside from the Great Dover Street Woman, physical evidence for female gladiators comes from a c. 2nd century CE relief found in Bodrum, Turkey which clearly depicts two of them, the above-mentioned inscription found at Ostia, a ceramic shard (thought to have been a pendant), found in Leicester, England, and a statue of a female gladiator (of unknown origin but in the style of the Italian peninsula) currently housed at the Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbein in Hamburg, Germany.

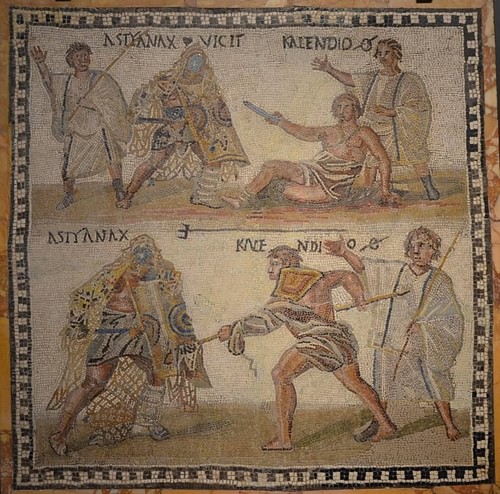

The relief depicts two women – clearly gladiators – and gives their stage names under their feet as Amazon and Achillia. They were most likely gladiators who enacted the famous story of Achilles and the Amazon queen Penthesilea (from Biblioteca of Pseudo Apollodorus, 2nd century CE) in which Achilles slays the queen in battle at Troy and then falls in love with her and regrets his actions.

Above the two figures is the inscription indicating stans missus, meaning the women had fought to an honorable draw. These two would have been Myrmillo or Samnite gladiators based on their shields and swords. The two round objects by each of the figures' feet are thought to be their helmets; but what type of helmet is unclear. The women in the relief must have been popular performers to have merited the expense of the work.

The ceramic shard is inscribed Verecunda Ludia Lucius Gladiator which translates as “Verecunda the performer and Lucius the Gladiator”. As noted, ludia can be interpreted as “female gladiator” and this ceramic has been claimed as proof that this Verecunda performed as one. Conversely, it could be interpreted to mean that she was simply an actress who was Lucius the gladiator's girlfriend.

The statue in Hamburg, which for years was interpreted as a woman cleaning herself with a strigil (a curved implement for scraping the body during bathing) is now understood as more likely a female gladiator holding a raised sica. The figure stands in a triumphant pose with the sica held high, bare-chested, in only a loincloth. This depiction fits the descriptions of female gladiators who, like their male counterparts, fought topless in only a loincloth, minimal armor protecting the shins and arms, and a helmet.

The statue is thought to represent a female thrax gladiator who has discarded her helmet in victory (as was common practice) and raised her weapon in triumph. Critics of this interpretation note that the figure is not wearing a greave (shin armor) and so is probably not a gladiator; but the band around the figure's left knee could be a fascia, a band worn to protect the knee under the greave.

Literary Evidence for Gladiatrix

There is also ample literary evidence to support the existence of female gladiators. The Roman satirist Juvenal (l. 1st/2nd century CE), medical author Celsus (l. 2nd century CE), historian Tacitus (l. 54-120 CE), historian Suetonius (l. 69-130 CE), and historian Cassius Dio (l. 155-235 CE), among others, wrote on the subject and always critically.

In his Satires, Juvenal wrote:

What sense of shame can be found in a woman wearing a helmet, who shuns femininity and loves brute force...If an auction is held of your wife's effects, how proud you will be of her belt and arm-pads and plumes, and her half-length left-leg shin-guard! Or, if instead, she prefers a different form of combat how pleased you will be when the girl of your heart sells off her greaves! Hear her grunt while she practices thrusts as shown by the trainer, wilting under the weight of the helmet. (VI.252)

Tacitus notes:

Many ladies of distinction, however, and senators, disgraced themselves by appearing in the Amphitheatre. (Annals, XV.32)

Cassius Dio expands on Tacitus' description:

There was another exhibition that was at once most disgraceful and most shocking, when men and women not only of the equestrian but even of the senatorial order appeared as performers in the orchestra, in the Circus, and in the [Colosseum], like those who are held in lowest esteem. Some of them played the flute and danced in pantomimes or acted in tragedies and comedies or sang to the lyre; they drove horses, killed wild beasts and fought as gladiators. (Roman History (LXI.17.3)

Conclusion

Scholarly consensus on the existence of female gladiators is far from uniform but the evidence from Roman sources weighs heavily on the side of accepting them as historical reality. The arguments against this claim largely hinge on interpreting ancient Latin texts and what certain terms – such as ludia – may or may not have referred to. Even so, it is difficult to understand how one can dismiss the relief of Amazon and Achillia or the literary and legal works which clearly indicate women's participation in the games as gladiators.

Women may have been considered second-class citizens by the patriarchy but this does not mean every woman accepted that status. Many high-born women were able to exert considerable control over their husbands, homes, and even at court. Juvenal, in the same book of his Satires noted above, makes clear exactly how powerful women could be, in fact, in controlling men who still believed they were the masters. In the case of female gladiators, it seems some women were not content even with that level of autonomy, however, and sought to control their own fate in the arena.